Latitude: 59 50.217N Longitude: 172 04.540WI stumbled into the main lab at 10.30 pm last night, already a little sleepy from a day of webcasting, multicoring and VanVeen grabbing. I was tired but determined to stay up with the mysterious Krill Gang for the night before I ran out of days to do it. The first person I found hovered above a microscope was Tracy Shaw, a technician at NOAA's Hatfield Marine Science Center in Oregon. Fresh from a day of sleep, her workday was just getting warmed up as most of the ship was heading to bed. At her workstation a Tupperware was swimming with krill that she has been experimenting with almost a month. These little guys have been very hungry. They are unwilling participants in a "starvation experiment" that she has been carrying out as part of an overall look at how krill live in the Bering Sea and what they eat along the way. The starvation part is important because they are looking to find out how long certain foods take to show up in the krill's body composition. They want to know how the body composition changes over time in the days after they eat a certain food. This way they will be able to tell what and when the krill that they catch have eaten. The inhabitants of Tracy's bowl had feasted on a buffet of ice algae and now they were ready to be measured.

Krill are "vertical migrators", meaning that they travel up through the water column at night to feed in the dark. In order to study these guys while they feed, the scientists that study them have to adapt their sleep schedule to work "krill hours". These are a far cry from banker's hours. The krill team comes up at night to feed too. Breakfast for these guys is usually after most people aboard the Healy have eaten dinner. At 11.00pm the night-shifters convene in the Mess Hall to eat "mid-rats" (the late dinner) together. This is just the beginning though. Bongos go out at 2am and there's work to be done beforehand.

Last night, I was in the lab and on the fantail at some pretty ridiculous hours to find out what the vertical migrators and their night-owl scientists do in the wee hours!

While Tracy is trying to find out what these critters eat, other members of the team are working to solve other mysteries.

Who's out there? Dr. Evelyn Lessard, from University of Washington is the Co-Chief Scientist for the cruise. She is also the head of Team Krill. As a microplankton ecologist, she generally studies organisms much smaller than krill but aboard the Healy she is interested not only in the plankton but in their relationship to the krill population. Before the cruise begins, Evelyn knows what types of experiments she will be conducting. Each sample is unique though. When a water sample comes off the CTDA research tool that is submerged in the water to measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth., it's only a guess which investigations will be appropriate for what's in that sample. That's where her FlowCam comes in. By taking a small sample of the seawater and running it through this instrument, Evelyn can tell right away who or what she's got in there.

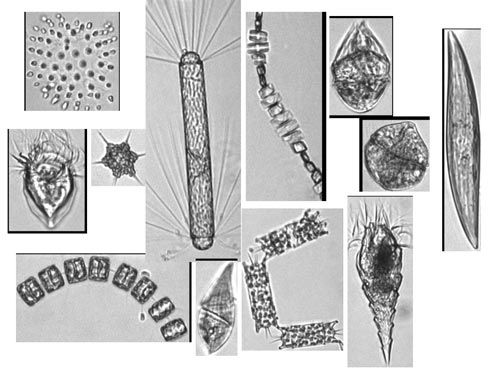

Once she has a peek into the microscopic world in the sample, she can make decisions about which kinds of experiments she will learn the most from. So what does she see through this magical FlowCam? Using a white light, a green laser and a digital camera, this mega-microscope captures pictures of plankton that you can't easily see. These guys are small and beautiful!

Even an expert like Evelyn will admit that the microzooplankton world is a very confused one. Organisms that seem like plants eat other organisms. Organisms that seem like animals produce their own food and there are even organisms that no one knows how to classify yet! (More on all this later). During Evelyn's career much has been discovered. She says, "One of the exciting things about my field is that when I started [microzooplankton] had been virtually ignored because when you pull up a net you can't see them!" Luckily, Evelyn can see, sort, classify and discover them.

So what's this have to do with krill? The big picture in the krill department is the idea that by looking at the population from many different angles, the team will get an idea of population dynamics under different conditions. Evelyn explains what the main idea is, "We are trying to determine how critical the ice is to their survival." Each member of the team has their own question work on so that they can contribute their data to the krill-conversation.

How old are they? Dr. Rodger Harvey and Rachel Pleuthner are from the University of Maryland, not so far from Oyster-Adams School! Rachel was breaking down her workstation when I arrived in the lab. As we near the end of the cruise, experiments are being packed away little by little. Until now, Rachel and Rodger have spent the last five weeks staring deep into krill eyes. Eye tissue is one of the places that krill accumulate a substance called "lipofusion". Lipofusion is a waste product that piles up over time in neural tissues. The older the krill, the more there is. But how old? That's what their team hopes to figure out. By working with another scientist (stay tuned to find about Alexei Pinchuk), who will begin raising krill, Rachel and Rodger are trying to establish an index for how much lipofusion indicates a certain age. Why is this important? By looking at the population of krill for a given year, biologists can identify environmental influences on the population. This can help answer questions like- Was there enough food in the past year to allow krill to get healthy enough to reproduce? Or...How old does the average adult get? Knowing how old or young a population is helps the krill team to understand the lifecycle, environment and dynamics of the communities.

Who Eats What? Meanwhile, Gigi Engel is bundled up, hovering over a tray of microscopic organisms with a "Crazy Straw" in her mouth. She is looking for "protists", single-celled organisms like phytoplankton, microzooplankton, ciliates and dinoflagellates. These itty-bitty consumers often have something called "biomarkers" that help identify them. The biomarkers are lipids, or fats that are unique to certain organisms. Once these little guys get eaten by predators, the "biomarkers" turn up in bigger organisms, Looking for these markers can help biologists and ecologists understand the connections in the food web. This type of tracing has been done in other populations but according to Gigi, no one has really explored it in protists yet. "That's where I come in," she says. She is capturing cells in a filter lodged in her crazy straw-looking device. Next week, she will take these little pets back to Seattle with her and continue her work.

After 21 hours of science, my brain had taken in all it could handle. Four in the morning is way past my usual bedtime but the Healy is definitely an unusual place! Stay tuned, there's five days to go and you never know what could happen next!

Comments