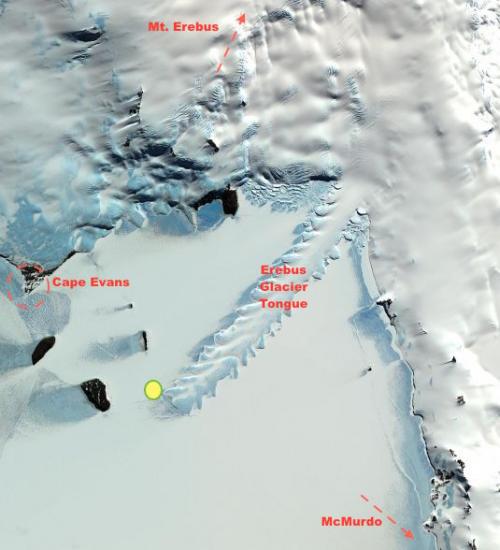

Foraminifera are protists and can be found all over the world in both fresh water (a very few) and marine waters, primarily living in the seafloor sediments. You've encountered them often though you may have never known it since they are single-cellular and are generally smaller than 1mm. This group of organisms is older than our species (homo sapiens), having existed for at least 550 million years. Here in Antarctica they have grown to a considerably larger size, some reaching a diameter of over 4mm – that may not seem significant but consider that most foraminifera cannot be seen with the naked eye. One particular research project here is studying the foraminiferan Astrammina rara and I've been able to join them for a few days as they find, collect, and investigate this local McMurdo organism.

Out in the Field

Continuing in the Footsteps of History

It's hard to escape the exploration history of the area – the overlapping expeditions and the repeated names of the men that continued to come down to Antarctica. The dive hut is situated near Scott's Hut, built in 1911 by the Terra Nova Expedition (British Antarctic Expedition of 1910–1913) led by Robert Falcon Scott. In a previous journal, I had written about Robert Falcon Scott's other hut – Discovery Hut – which is located on Hut Point right next to McMurdo Station. Scott opted to not reoccupy his former building for this expedition, choosing instead a site that was slightly north, with the hope that it would not result in being trapped by the ice as his previous expedition had become. In 1911, Scott and his men set out from this site on a bid to reach the South Pole – as it turns out, a fatal trek for them.

The cross in the photo that can be seen in the upper right atop the hill was in memory of the three members of Shackleton's Ross Sea Party, who died nearby and is unrelated to the Scott expedition that had originally built the hut at Cape Evans.

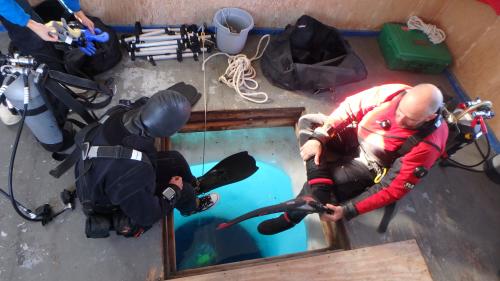

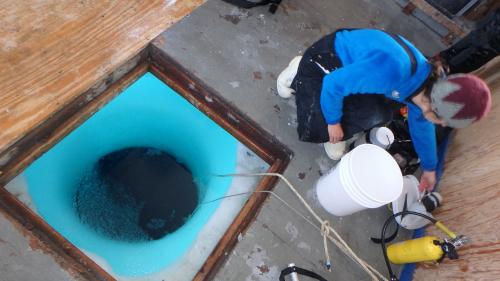

Back in the Dive Hut

The now crowded dive hut is dominated by the large blue glowing hole in the middle. The hole, having been previously drilled by the McMurdo dive crews, is the only entrance and exit around the area for both the divers and any equipment or specimens. The divers will go down for two dives today with a single one hour break in between dives to warm back up (the water is -2°C), have some lunch, and get ready for the next dive. On the first dive, they are going to be collecting Amanda's samples of ocean floor sediment from within the top centimeter or so (that's where the foraminifera live) and the Antonio and Miles' batch of starfish. All of the collections are attached via carabiners to the dive rope (which also doubles as a flag and light tower to show the divers where the dive hole is located – it can be slightly disorienting under the ice from what they say).

Once the sediment arrives, it needs to be sorted and the larger material discarded. Using a series of improvised sieves, larger parts of the sediment are separated from the smaller which are allowed to fall through to the next stage. As the sieving continues, the particles of sediment (and any organisms as well) that are between 1mm to 6mm are kept and set aside for examination later in the Crary Science Facility at McMurdo Station. The collected sediments are then clipped back onto the dive cord so that they can be kept cool in the water. The sediment that is not needed (those sediments that are larger than 6mm or smaller than 1mm) are set aside and will be disposed of down the dive hole once diving has finished for the day.

Back in the Crary Science Lab

The equipment at Crary Science Lab is state-of-the-art and all provided by NSF to scientists and researchers who are working in the field and here at McMurdo. Some equipment is specialized to the point that researchers will need to provide it themselves, but many things that you would expect in high-end stateside labs are available for use. The microscopes themselves are quite expensive owing to the need for clarity and accuracy when viewing, as well as myriad of other items such as cooled stages, hook ups for video and photography, and more.

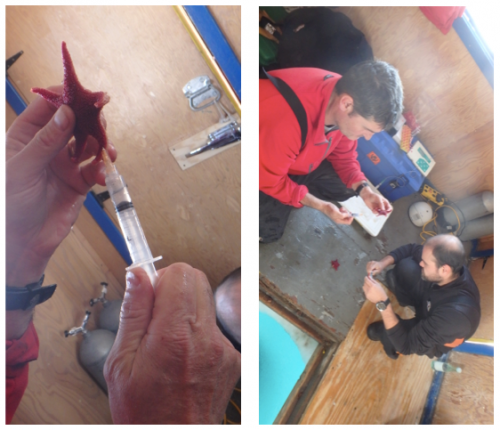

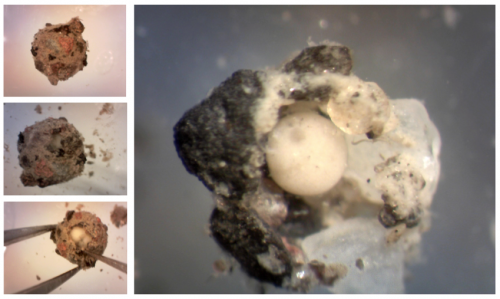

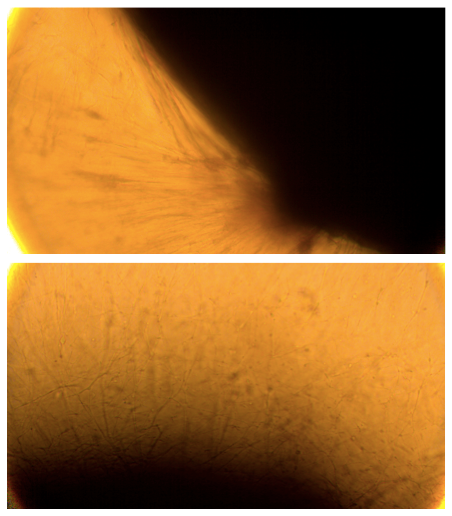

Astrammina rara, unlike other species of foraminifera, does not make its "shell", or test as it is properly called, from calcium carbonate, instead procuring the items needed for its test from the immediate area. The foraminifera is able to extend out its thousands of pseudopods to collect available grains of rock of the proper size. It then secretes a bioadhesive (essentially a glue) to bind together these grains into a solid test in which it lives. This form of foraminifera is called an aglutinated foram because of this. When the test is removed, not surprisingly the now "naked" foraminifera extends out its psuedopods in a quest for grains to make another test and also begins secreting the bioadhesive. It would take the foraminifera roughly 1-2 weeks to fully reconstruct its test.

The bioadhesive is what is of considerable importance and this project is working to understand the mechanics and the biology of it. They will be using the bioadhesive for amino acid analysis, trying to get an idea of its composition and what genes and proteins are involved in its production. As part of this, genomic sequencing of the foraminifera will also be conducted.

Bioadhesive from Foraminifera? Why do we Even Care?

There are a number of applications of this adhesive in the biomedical field. The adhesive that is produced has the capacity to harden under saltwater and since we are salty organisms that means that this adhesive could be used inside of our bodies during medical procedures. There could be applications with eye stitches, dental work, or areas where stitches themselves are just not possible. Of considerable importance to Amanda's work is its inherent ability to bind to heavy metals – notably iron. In addition to the biomedical field, the area of environmental health could benefit from these little guys.

Here in McMurdo, the Navy used to dump a large amount of industrial refuse into Winter Quarters Bay – refuse that included heavy metals. A 2001 New Zealand survey of the seabed at Winter Quarters Bay revealed 15 vehicles, 26 shipping containers, and 603 fuel drums, as well as nearly 1,000 miscellaneous items. In addition, sediments in the bay are contaminated with PCBs, metals, and fuels – likely from the former landfill above the bay, ship bilges, and shop wastes. You can read more about the conditions in Winter Quarters Bay from past PolarTREC teacher Michelle Brown's journals. Those items now have a large number of organisms living on and around them. We know that other animals that produce a bioadhesive such as mussels, barnacles, and some types of worms that make tubes, that the iron ion is used to facilitate the curing (hardening) process. The idea here is that if the animals are using the iron ion (a heavy metal ion), then other heavy metal ions that are more hazardous to humans might also used as a facilitator to the bioadhesive. In the absence of iron, will Astrammina rara use other heavy metal ions as substitutes?

Astrammina rara are found throughout the McMurdo Sound area and another portion of the team is on the other side of Sound at Explorers Cove also collecting foraminifera. These foraminifera can be used as a comparison to those found in Winter Quarters Bay to determine of the foraminifera here are behaving differently or have adapted to their more heavy metal laden environment. Who knows perhaps someday a bioadhesive from a tiny foraminifera could be helping us to clean up some areas that harbor the worst contamination in the world ... stay tuned!

Comments