What is PolarTREC?

PolarTREC (Teachers and Researchers Exploring and Collaborating) is a program in which formal and informal educators spend 3-6 weeks participating in hands-on field research experiences in the polar regions. The goal of PolarTREC is to invigorate polar science education and understanding by bringing educators and polar researchers together.

Summary of Science

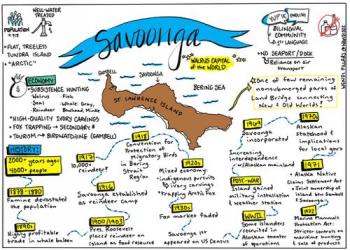

The primary objectives of this particular research project are twofold: 1) track the winter migration of seabirds using loggers and 2) measure both their response to late summer and late winter environmental conditions through blood, feathers, and reproductive performance. Savoonga, Alaska (St. Lawrence Island) is a haven for many seabirds and has been home to this research for three years (summers of 2016-2018).

Overall, the larger goal of the three year research has been to determine how these Arctic seabirds are interacting with sea ice and the multilayered cause and effect of oceanic conditions, particularly food availability and quality. In 2018 there was historic low winter sea ice; it was present for the shortest amount of time on record and disappeared from the Bering Strait earlier than ever before. Shore ice on St. Lawrence Island never developed, exposing coastlines to erosion and hampering people’s access to winter hunting areas. On the other hand, no sea ice provides "good research conditions" because years with contrasting ocean conditions in such a short study period can be ideal for sussing out the role of sea ice in the seabirds’ annual cycle.

Expectations and Outcomes

1. Expectation: I expected to start working in field conditions right away based on our pre-field calls and emails.

Reality: There was no time wasted: I went into the field the morning directly after an evening arrival.

2. Expectation: I wanted to do “real research” and understand the processes behind data collection, especially with birds, because this was totally new territory for me.

Reality: I learned that real research is intense, on-the-ground gritwork. The saying that “time is money” is very true, hence the 7 days a week work schedule. Mission truly drives the schedule, although the animals don’t necessarily agree to the study mission or cooperate with any particular schedule. I also realized just how physical the work could be, rappelling down cliff-sides, climbing over rocks, walking across very uneven alternately rocky and quaggy tundra, battling the elements, and four-wheeling to our worksites--a journey where neither the rider nor the driver could relax their attentions.

3. Expectation: I wanted to understand more about seabirds, their nesting habits and how it was even possible to catch /log / track birds. Reality: Everyday was a new experience, learning different capture methods and productivity monitoring processes. To understand the bigger picture, it was so important to comprehend the many nuances of day to day work and findings. Every evening was a critical debriefing period that included celebrations, brainstorming, and problem-solving, albeit informally over dinner or after dinner conversation as the team all worked on their different documentation requirements.

Top 3 Unexpected Takeaways

1) I was really nervous before I went because I had never done field research with birds, and I was worried about being more of a hindrance than a help. What I realized was that not knowing is actually liberating, and it allowed me to feel comfortable asking questions, plus it spurred me to research more even before I went to Savoonga.

2) Another powerful takeaway was the underestimated link between the Siberian Yupik and the seabirds. Particularly in a subsistence culture, the changes birds undergo impact human lifestyles but also serve as “sentinels” of Arctic change due to their range, diet, and own unique lifestyles.

3) I didn’t expect to become so invested in the well-being of the birds, to get to know them “individually”, even if that meant by nest number and through binoculars. Seeing the murres in their final hours was mystifying and saddening, and knowing that all of the auklet chicks died in mid-August was heartbreaking to learn. Despite knowing that seabirds have long lives, and that one year of no chicks may not be detrimental, I felt frustrated not understanding why. I couldn’t help but wonder how many changes wrought by humans were causing the challenging breeding conditions I witnessed.

Importance of Teacher/ Researcher Collaboration

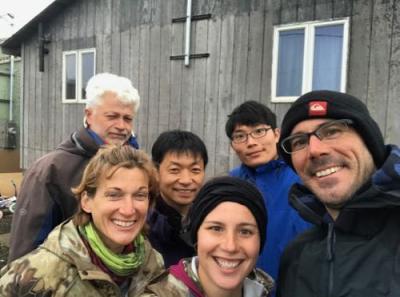

During my time in the field I relished the mutual brainstorming,

Linking to my Classroom

As a teacher of English language learners, I use a lot of nonfiction text as a vehicle for teaching language because it helps me connect their learning to content area classes, especially science and history.

1) Persistence: The mentality of working until something is done, and crafting work-arounds when your initial and beautifully planned ideas fall through. Unpacking what might seem to be a simple question, can lead to many others. Finding the answer to your original question doesn't mean your work or research is done!

2) Integrity: The idea of being beholden to teammates resonates across so many areas. You’re at once humbled and strengthened by the force of the team and its vision. No job is too small, and flexibility is key to getting work accomplished.

3) Integration: As a Language teacher, skill development progresses more rapidly when my reading and literacy lessons tackle subjects like science and history. My experience in the Arctic really brought home that there is no “pure” field. The scientists I worked with draw on many fields and skill sets to conduct their research, continue to cultivate relationships within the community, and to interpret the information they collected. Interdisciplinary lessons pack a powerful punch so, motivated by my recent experience and with a new appreciation of how different subjects come together to understand the Arctic, I plan to team with the Biology, Earth Science, and World History teachers.

One specific idea I’m currently working on is to develop a multi-faceted unit, that compares and contrasts human and animal migration, with the animal piece honing in specifically on seabirds. This will include incorporating migration data from the loggers retrieved this summer. I’m using the Polar Literacy Initiative, specifically Polar Literacy Principle #6, as a guide to building lessons which look at the integral symbiosis of humans and the Polar system.

Post-Expedition Plans

I have continued to read and research, and even re-read articles I’d read pre-expedition because now they hold new meaning. I’ve also been blessed being able to continue asking questions of my Principal Investigator Alexis Will, as I learn more with the tracking data of the auklets and graphic representations of nest productivity. Each new data set sparks more ideas for classroom connections. I plan to partner with both science and history colleagues to highlight both the human and animal aspects of migration,

I will be presenting at a nearby Audubon Society Chapter about my expedition and the research, and have been in touch with one of its members who will help me with resources and possible field experiences for my students. The North Carolina (NC) Zoo has invited me to present at their Lunch n’ Learn with zoo staff to share what I have learned, and we have briefly discussed creating even a small display of photos and information for the public. A fellow NC PolarTREC teacher and I are considering how we can co-present as “polar opposites” based on his journey to Antarctica and mine to the north. Alexis and I hope to finalize a PenPal schools unit on the Arctic this fall, and my ultimate goal is to write a student-friendly book about the Arctic within the year. Other presentation invitations have come from two local Rotary clubs, a church, and possibly a library, but it’s just a matter of getting time off from school to attend meetings which are typically held during the day. I will continue to make sense of my research through sketches and art to share with others.

I feel it’s more important than ever for administrators at our school, district, and state level to understand the value of allowing teachers time and space to pursue immersive opportunities like these. Even though the primary goal of the research was related to seabirds, I learned that the human factor was inextricably linked, and I’ve found myself reflecting on how to make my instruction more relevant after learning how Siberian Yupik students demonstrate intelligence in ways we would never dream of (fixing an engine, harpooning marine mammals, harvesting leaves and berries). It has forced me to rethink my own work with language learners and brainstorm ways to better discover their strengths. Providing examples to policymakers of small lessons (rather than a one-off unit) that have been borne of my experiences highlights how an experience like this manifests itself in so many unexpected ways. I find myself thirsting for more, and I feel that, too, will resonate with administrators and boards of education.

Expanded Goals and Vision

My vision is to continue researching the Arctic and polar science, and I will continue to integrate a broader scope of science in my language classes.

*This program is supported by the National Science Foundation under award 1345146. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed by this program are those of the PIs and coordinating team, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Download Report (PDF - 1.45 MB)1.45 MB | 1.45 MB |

This program is supported by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed by this program are those of the PIs and coordinating team, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.