The PolarTREC Field Experience

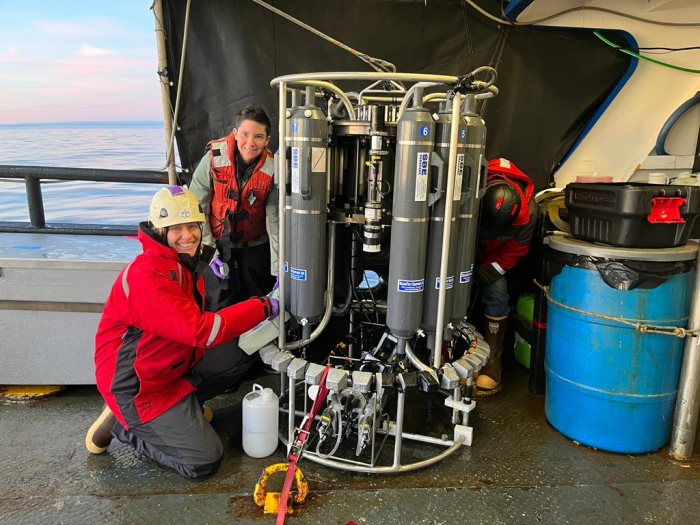

From July 19, 2022, to August 15, 2022, I participated in the Harmful Algal Blooms in Arctic Waters research cruise on the R/V Norseman II. The Chief Scientist was Dr. Robert Pickart from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), and the research team included scientists from WHOI, Oregon State University, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the University of Alaska, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

During the cruise, the science team collected data along a series of transects in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas. The team completed 200 CTD casts. 354 water samples were collected from the rosette and underway sampling systems for enumeration of the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella. 300 water samples were filtered from the rosette and underway sampling systems for molecular detection of Pseudo-nitzschia, along with 300 paired samples to be analyzed for domoic acid. Net tows were conducted at 33 stations. 19 concentrated toxin samples were collected from the underway seawater system. The team deployed a Smith-McIntyre grab at 106 stations and collected over 160 clams at station DBO3-12, for an underway toxin depuration experiment. Multi-cores were collected from 5 sites. The team also collected continuous underway data from an Imaging Flow Cytobot (IFCB), a mass spectrometer, and an Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler. All of this was accomplished in sometimes heavy seas and despite unexpected sea ice that necessitated a large-scale change in plans.

The Importance of Educator/Researcher Collaboration

When you only experience science in a classroom, through a textbook, or through the news, it is easy to see science as a set of unchanging facts. The experience of participating in scientific research reminded me that scientific knowledge is ever-evolving. It was exciting to ask questions to which the answer was “we aren’t sure at this time,” and while writing my journal entries I had to be careful with my language to make sure I wasn’t making things seem more certain than they are. I aspire to use my experiences to make this more apparent to my students I hope that seeing science as an iterative process, rather than as a set of facts, will deepen their curiosity.

One of PolarTREC’s biggest benefits to me was the opportunity to develop culturally relevant and place-based learning opportunities for my students. Many of the learning materials that they are given, such as text books, curricula, and videos, feature phenomena like roller coasters that have little to do with their lives and experiences. The expedition taught me about research taking place in the Bering Strait region, which has allowed me to prepare lessons that teach the science based in our area. Additionally, I hope for my students to learn to do science for themselves. In the past I have focused on skills such as making models and planning investigations. Onboard the ship, I was reminded that science is collaborative. Now, I will add in teaching students the skills they need to collaborate with one another while they do their science.

It was very inspiring to meet the scientists and learn about the paths their lives have taken. I hope that I was able to be helpful to them. One benefit I can see in having a teacher onboard was that I was able to provide some context about life in our region. Additionally, one scientist commented to me that explaining her research to me helped her to think about how to communicate her research. She mentioned that it can be hard to know where to start when explaining her work to non-scientists and seeing how I broke down the research into different concepts for the journal entries helped her strategize about this.

Summary of the Science, or The Science Explained

Harmful algal blooms are caused by phytoplankton — microscopic, plant-like organisms living in all the world’s oceans. When phytoplankton are exposed to the right conditions they can “bloom”, or multiply extremely rapidly. Occasionally plankton blooms are hazardous to human or marine life. These are known as “Harmful Algal Blooms” or HABs.

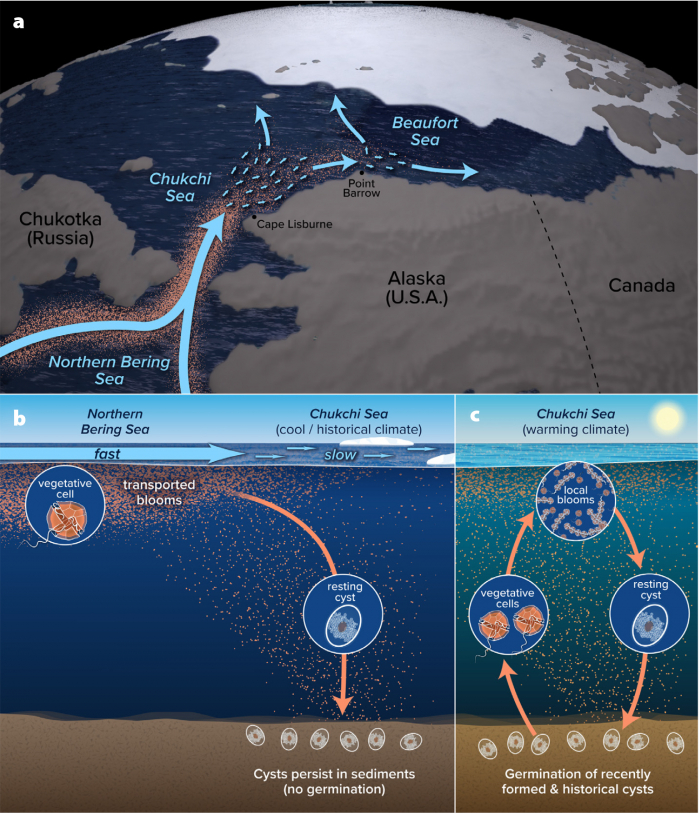

In Alaska, the most destructive HABs are caused by two groups of phytoplankton that can produce deadly toxins – Alexandrium, which can cause paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP), and Pseudo-nitzschia, which can cause amnesic shellfish poisoning. Climate change is causing oceans to warm and scientists have now found Alexandrium and Pseudo-nitzschia, which are prevalent farther south, in the Bering Strait and Chukchi sea.

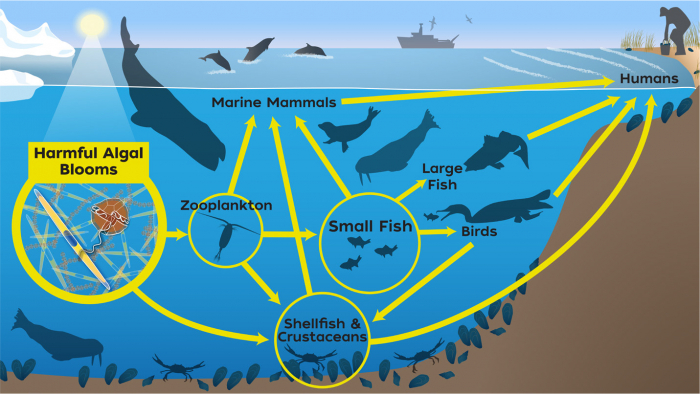

Just as red tides and other HABs have affected ecosystems and communities further south, HABs in northern Alaska pose a threat to the health of both humans and marine organisms. Clams living on the seafloor filter feed on plankton, which can cause HAB toxins to accumulate in their tissue. Humans or marine mammals, such as the walrus, who eat these clams can get PSP, a potentially fatal illness. The expedition scientists studied the risk of HAB toxins passing through the food chain by collecting clams and worms living in the seafloor sediment in order to analyze them for toxins.

Alexandrium is a phytoplankton, meaning it uses sunlight to make energy. It has a unique lifestyle, starting its life as a cyst, a small seed-like particle that lives in the seafloor sediment. In the right conditions, the cyst germinates into two Alexandrium planktonic cells swimming in the water column. The plankton can replicate itself through cell division, and the duplicates eventually reproduce, creating more cysts. The cysts can survive harsh conditions that would kill an Alexandrium in its planktonic state. The expedition scientists studied Alexandrium by sampling seawater for Alexandrium plankton and by sampling the seafloor sediment for Alexandrium cysts in order to create a map of cyst beds in arctic Alaska.

There are 15 or so species of Pseudo-nitzschia phytoplankton in northern Alaska. Many of them look very similar, and can only be distinguished through their DNA. Some species of Pseudo-nitzschia produce domoic acid, the toxin that causes amnesiac shellfish poisoning. Unlike Alexandrium, Pseudo-nitzschia spends its entire life as a planktonic cell. Expedition scientists studied Pseudo-nitzschia by filtering it from water samples in order to better understand which species are in the region and how toxic they are.

Linking PolarTREC Science to my Classroom and Community

Over the course of the expedition, I wrote 21 journal entries, posted updates on Facebook, posted videos to YouTube, and presented over Zoom to teachers, researchers, and community members in Spain and the US.

I spent a great deal of time engaging with all the scientists and seafarers aboard the ship. I interviewed the whole crew and almost all of the science party members about the path that led them to where they are now. I asked each one four questions: What is your job on board? What is your job when you are on land? How did you come to be aboard this vessel? and What was your path to the job you are doing now? I asked these questions because when I was in high school I had no idea that some of these jobs existed, let alone how to pursue them. I wanted to give my students the chance to learn about as many jobs as possible so that they have the opportunity to explore careers that interest them.

When I returned to school, I immediately began sharing my experiences with my students as a teaser for what we would learn as the year went on. I gave a zoom presentation about HABs in the Bering Strait region to my fellow science teachers at the Bering Strait School District. During the expedition, the Norseman scientists and the Norton Sound Health Corporation put out two health alerts about Alexandrium blooms in the region. On the first day of school, I gave a short presentation about these alerts to students and their families.

In this coming school year, my middle school students will do an oceanography unit in which they will learn how water masses form in the ocean and how scientists collect data about the ocean. They will use what they learn to develop scientific questions about how the water changes over the fall in Brevig Lagoon and then collect data to carry out this investigation. My high school biology students will study HABs, focusing on the question of how HABs are connected to climate change and local health. They will also study plankton ecology by investigating the plankton communities in two of the water bodies bordering Brevig Mission: Port Clarence and Brevig Lagoon. Both classes will then use digital storytelling to present their findings. My life skills class will learn about maritime careers. They will use what they learn about maritime careers to investigate other careers that might be of interest to them.

Expectation and Outcomes

The opportunity to work with scientists deepened my understanding of the ocean and plankton. It was awe-inspiring to see how many things are unknown and learn about the ways that scientists are trying to answer these questions. Although I have only been back from the expedition for a month, I have already seen that learning about my experience has helped my students become more engaged with science. When they look at pictures or videos from the expedition, they ask many thoughtful questions. .

Further Education and Outreach Opportunities

Participating in the expedition has opened up a few new opportunities for my students to engage with scientific research. In October, PhD student Evie Fachon, who was aboard the Norseman II, will visit Brevig Mission for a week to work with the students. This will be an exchange of information in which she will teach the students about her research, and they will teach her about this region.

Bob Pickart, the chief scientist on the Norseman II, will be on an expedition to study the Beaufort Sea onboard the RV Sikuliaq during the month of November. My class will be one of three schools following along with the expedition. They will interact with the researchers and with students at schools in other parts of the country.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Download Report (PDF)2.44 MB | 2.44 MB |

This program is supported by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed by this program are those of the PIs and coordinating team, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.