We learned before that the amount of tritium in water can be used as a stop watch. Today we are going to learn about other tracers used for determining the age of water masses, CFCs.

We are going to follow the team that measures the CFCs from sampling to analysis, but we will begin with a small introduction to CFCs for those who might need a refresher. Skip to 'Why measure CFCs?' if you do not need the introduction.

CFC is an abbreviation for man made compounds called chlorofluorocarbons. These compounds were developed in the 1930's to be used as refrigerants and aerosol propellants. They were widely used in industry because of their useful and unique properties. They condense and evaporate in a small pressure range compare to other gases, which make them great for cooling systems such as refrigerators and air conditioners. They are also non flammable and non-toxic, which make them great as propellants (what sends the hairspray out of the can). So, what happened to them?

The problems with CFC became apparent in the 1980's. It was discovered that CFC rise into the stratosphere (a layer in the atmosphere above 10 km) where they react with and reduce the amount of ozone. OzoneOzone is a molecule made up of three atoms of oxygen. Ozone occurs naturally in the stratosphere and provides a protective layer shielding the Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. In the troposphere (the lower layer of the atmosphere up to approximately 15 km above the earth's surface), it is a chemical oxidant, a greenhouse gas, and a major component of photochemical smog. in the stratosphere is good for life on earth as it absorbs some of the harmful ultra violet rays. Less stratosferic ozone means more UV rays which produces cancer. It should be noted that ozone is bad for us to breath, so it is considered a pollutant when found at the surface of the earth, but that is another story. In a great show of environmental concern and action, most industrial countries agreed to end the production of CFC by 1997 on what is known as the Montreal protocol. By 1997 only 10% of the peak production was produced.

There are more than one type of CFC. Generically they are also known as freons, the gas used on refrigerators. Oceanographers measure the following CFC: CFC-11, CFC-12, CFC-113. Each gas was released to the atmosphere at a different known concentration over the years.

Why measure CFCs? Why do we measure in the ocean compounds that have essentially not been produced since 1997?

The ocean and atmosphere exchange gases; when the concentration of a gas is higher on the air than the water, the gas flows to the water, and vice versa (see the March 22 entry for a more detailed explanation).

CFCs in the atmosphere dissolve into the ocean only through its surface, and they essentially do not react with anything in the water. CFC are also only made by humans, there are no natural sources, which makes them great as tracers for water masses. Surface waters eventually sink to greater depths in certain regions of the world taking the CFCs with them. We know what the proportion among the different CFCs was in the atmosphere every year, so we can match the proportion of CFC found in water masses to the atmospheric values and thus date when water masses were at the surface (see April 2 for a more detailed explanation). The actual process is more complicated, since the solubility of each gas in seawater is different, but that is the general idea.

The CFC group also measures another man-made gas that is found in the water for a similar reason. Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), is a gas used mostly as an insulator in electric equipment. It is a green house gas, but that is not the reason for measuring it in the water. It is another gas that we can use as a stopwatch (see entry of April 2). People measure SF6 because the CFC levels in the atmosphere have been plateauing in recent years, thus making CFCs less useful for dating younger water masses. SF6 is still being produced and used to date. Its atmospheric concentration is on the rise, making it potentially more useful for dating younger water masses.

Here is how we measure the CFC and SF6 on the boat. These samples are the first samples to be taken from rosette bottles to prevent t gas exchange. We take a 500 ml sample in a glass bottle. The bottle is rinsed several times before being filled.

The bottle is caped and the cap fixed with a green plastic holder and placed in a plastic cup. The cup is filled with water from the same niskin bottle, completely immersing the sample bottle tin order to achieve a water seal. Here is a box with some of the samples from a rosette.

The samples are analyzed right away in a very strange looking machine. Most of the machine is home made by the scientists and technicians. It has taken several years to develop them and you cannot find them in a store. The sample bottle is placed on a tray and connected to a hose.

The hose removes the right amount of sample and places it on a glass tube with an aerator on the bottom. The SF6 concentration in the ocean is typically much lower that that of CFCS, so we need a larger amount of water for measuring SF6 than for CFCs. The aerator produces very small bubbles of nitrogen forcing the dissolved gases to move from the water to the bubbles. The gases go from the water to the nitrogen bubbles because there is less partial pressure for all gases, save nitrogen, in the bubbles than in the water (see March 22 for a discussion of the effect of partial pressure).

Very cold temperatures (-87C) generated by the expansion of liquid carbon dioxide trap the purged gases carried by the nitrogen in columns of materials designed to absorb these gases. Heating the columns then releases the gases and sends them to the chromatographer where different gases are separated.

You might have seen chromatography at work if you have dropped a drop of ink on a paper and seen the ink separate in different colors as it spreads on the paper. Each color travels at a different speed on the paper and that allows us to see the separation. A mixture of gases is passed through a glass tube with some special material that looks like sand. Each gas will travel at a different speed through the material based on their polarity, separating the mixture of gases into its components.

Each gas passes separately through an 'Electron Capture Device' that will measure the amount of gas is passing through. The electron capture device works with the same principle as smoke detectors do (I decided to write the more scientific explanation at the end of the entry for those who would like one, since I do not want to loose those who prefer a simpler explanation). At the end we get the amount of CFC and SF6 on a water sample.

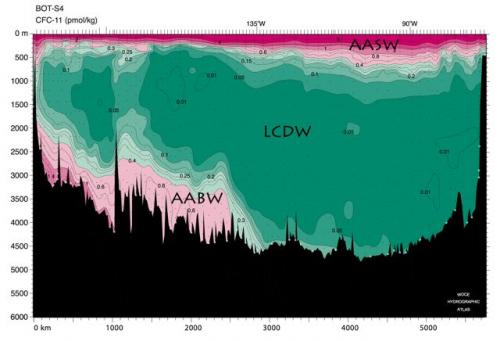

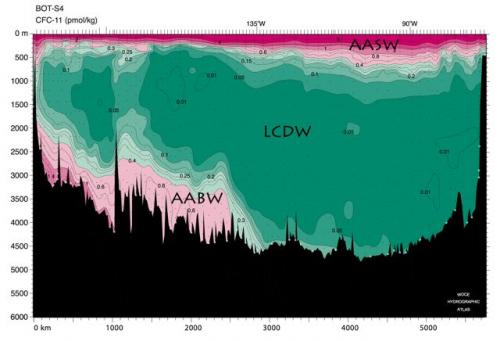

Let us take a look at a vertical section of CF-11 for the transect that we are sampling now, with data from 1992. The vertical axis is the depth in meters, the horizontal axis is the distance traveled by the ship and the contours and colors represent the concentration of CFC-11 with dark pink being the highest concentration and green the lowest.

You can see that the Antarctic Surface Water (AASW) is the water mass with highest concentration of CFC-11, while Lower CircumpolarLocated or found within the Earth’s polar regions. Deep Water (LCDW) has the lowest. We can say that AASW is the youngest water mass, the LCDW is the oldest and the AABW is in between. Remember that young and old is relative to how long ago the water left the surface of the Ocean. This is consistent with our idea of how each water mass is generated. The Antarctic Surface Water (AASW), a very fresh and cold water mass produced from summer melting of sea ice (see entry for March 9), has the highest concentration because it is in direct contact with the atmosphere. The Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW), cold and salty water produced by the winter freezing of surface waters, was produced longer ago. The LowerCircumpolar Deep Water (LCDW) came from the North Atlantic and was at the surface on the order of 100 of years ago, which is consistent with the very low CFC-11 values (remember that this is not pure North Atlantic Deep Water but was mixed at the CircumpolarLocated or found within the Earth’s polar regions. Current with other water masses).

It will be interesting to see the same section with the data that we are generating in the cruise and see how the concentrations have changed in 20 years. What do you think we might find at each depth?

Smoke detectors and Electron Capturing Device

Smoke detectors use a radioactive element, Americium, that emits alpha particles and a sensor that detects the particles. Alpha particles are made out of two protons and two neutrons. The smoke alarm will trigger when a gas gets in between the radio active element and the sensor and blocks the alpha particles. Smoke, which is made of gases and particles floating in the air, and water vapor can block the alpha particles.

The electron capturing device uses a radioactive isotope of nickel (Ni-63) that emits ß (beta) particles instead of Alpha particles. ß particles are electrons emitted from the nucleus of an atom when a neutron turns into a proton and an electron. The device has a sensor that detects the amount of electrons flowing. This system works for detecting compounds with halogens. Chlorine and fluorine are two halogens. What makes halogens different from other elements is that they require one electron per atom to be stable. They require it so much that they snatch an electron from wherever they can. That is why pure chlorine is harmful for us; it removes electrons from your atoms.

Halogens in the electron capture device capture the electrons that are the ß particles. The device can detect how many electrons did not make it to the sensor because they were captured by the halogens, and translates that into how much halogenated compounds are in the sample.

Sobre los CFC y SF6

Hace poco aprendimos que la cantidad de tritio en el agua de mar se puede usar como cronómetro para saber cuando fue la ultima vez que masas de agua se encontraron en la superficie. Hoy vamos a aprender sobre otros compuestos que se pueden usar para medirle la edad a las masas de agua: los CFCs.

Seguiremos al equipo encargado de las mediciones de CFC desde el muestreo hasta el análisis, pero primero veremos una breve descripción de los CFC para aquellos que necesiten un recordatorio. Puedes brincarte esta sección si estás al tanto de los CFC e ir a donde dice '¿Porqué cuantificamos los CFCs en el mar?'.

CFC es la abreviatura para designar a un grupo de compuestos hechos por el ser humano que se llaman clorofluorocarbonados. Estos compuestos fueron desarrollados en los años 30 para usarse en sistemas de refrigeración y como propelantes de aerosoles. Se usaron mucho en la industria por sus propiedades benéficas. Se condensan y evaporan en un rango muy pequeño de presión, por lo que son muy útiles en sistemas de refrigeración como refrigeradores y aires acondicionados. Son inflamables y no son tóxicos, lo que los hace idóneos como propelantes (lo que hace que salga el spray para el pelo de la lata). ¿Qué les pasó entonces?

El problema con los CFC se hizo aparente en los años ochentas. Se descubrió que los CFC viajan hasta la estratosfera (por arriba de los 10 km sobre la superficie) donde reaccionan con el ozono y hacen que disminuya la concentración de este gas. El ozono en la estratosfera es muy útil para la vida en la tierra como la conocemos ya que absorbe gran parte de los rayos ultravioleta que son dañinos. Menos ozono estratosférico significa más radiación ultravioleta lo que produce cáncer. Debo decir que el respirar ozono también es dañino, por lo que se considera a este gas como un contaminante cuando se encuentra sobre la superficie de la tierra. En una muestra de conciencia ambiental, la mayoría de los países acordó suspender la producción de estos gases en 1997 en lo que se conoce como el Protocolo de Montreal. En el año 1997 sólo se produjo el 10% de la producción pico de CFC.

Hay más de un tipo de CFC. También se les conoce como freones, por ser usados en refrigeración. Los oceanólogos miden la cantidad en el mar de los siguientes CFCs: CFC-11, CFC-12, CFC-113. Mientras se produjeron estos gases, se liberó a la atmósfera una cantidad diferente, pero conocida, de cada gas.

¿Porqué cuantificamos los CFCs en el mar? ¿Porqué medimos en le mar la cantidad de gases que se dejaron de producir en 1997?

Los océanos y la atmósfera intercambian gases; cuando la concentración es mayor en el aire que en el agua, el gas fluye hacia el agua y viceversa (Lee el diario del 22 de marzo para más detalles sobre el intercambio de gases).

Los CFC en la atmósfera entran al mar sólo por la superficie, y esencialmente no reaccionan con nada en el agua. No hay ninguna fuente natural de CFCs, lo que los hace buenos trazadores para masas de agua. Las aguas superficiales eventualmente se hunden y se llevan consigo los CFC que tomaron en superficie. Sabemos la proporción de concentraciones de los diferentes CFC para cada año, por lo que podemos buscar el año en que las proporciones en la atmósfera entre todos los CFC era igual a la del agua (lee el diario del 2 de abril para una mejor explicación). El proceso actual es más complicado, ya que se debe tomar en cuanta la diferencia en solubilidad de cada CFC, pero el principio es sencillo.

El grupo de CFC mide otro gas producido por el hombre que se encuentra en el océano por razones similares. Hexafluoruro de azufre (SF6), un gas que se usa como aislante en equipos eléctricos. Es un gas invernadero, pero no se le mide por esa razón. Es otro de los gases que se pueden usar como cronómetro (ver el diario del 2 de abril). Además, los niveles de CFCs en la atmósfera están nivelándose, por lo que dentro de algún tiempo no se les podrá usar para etiquetar masas de agua. El SF6 se sigue produciendo hoy día y su concentración en la atmósfera va en aumento, por lo que se convertirá en el trazador de moda en algunos años.

Así es como medimos los CFC y el SF6. La muestras de agua para estos gases son las primeras muestras en tomarse de la roseta para evitar el intercambio de gases con el aire. Se toman 500 ml de muestra de cada botella niskin en una botella de vidrio. La botella se enjuaga tres veces antes de tomar la muestra.

Se tapa la botella y se sujeta con un plástico verde. Se coloca la botella en un vaso grande de plástico. El vaso se llena con agua de la misma botella niskin y se sumerge en ella la botella de vidrio con la muestra para obtener un sello de agua. Aquí la foto de una de las cajas con las muestras listas para ser analizadas.

Las muestras se analizan inmediatamente en una máquina de apariencia extraña. Casi toda la máquina es de construcción casera y le ha tomado varios años a los técnico y científicos en desarrollarla, por lo que no se puede comprar en una tienda. La muestra se coloca en una repisa y se le conecta una manguera.

La mangera extrae la cantidad correcta de la muestra y la pone en un tubo de vidrio con un aereador. El océano tiene una concentración de SF6 mucho menor a la de CFC, por lo que se necesita una mayor cantidad de agua para obtener una cantidad de SF6 que se pueda medir. El aereador produce pequeñas cantidades de burbujas de nitrógeno que obligan a los gases disueltos a pasar del agua a las burbujas. Los gases pasan del agua a las burbujas ya que la presión parcial de todos los gases, excepto nitrógeno, es menor en las burbujas que en el agua (lee el diario del 22 de marzo para un explicación sobre la presión parcial).

La muestra se pasa por temperaturas muy frías (-87 C) que se obtienen al hacer expandir nitrógeno líquido para atrapar los gases en material diseñado específicamente para eso. Los gases se liberan al calentar el material especial y se les conduce a un cromatógrafo para ser separados.

Tu has visto cromatografía en acción si has dejado caer una gota de tinta en papel, y has visto como se separa en diferentes colores al desparramarse en el papel. Cada color viaja a una velocidad diferente en el papel y hace que se separen. La mezcla de gases se hace pasar por un tubo que contiene otro material especial que parece arena. Cada gas viaja a una velocidad diferente atraves de la arena por lo que los gases acaban separados.

Se pasa cada gas por separado por un 'instrumento atrapa-electrones' que mide la cantidad de gases que pasan por ahí. El instrumento funciona en forma similar a un detector de humo (decidí escribir la explicación científica sobre el instrumento y el detector de humo al final para mantener la explicación sencilla aquí). Al final sabemos la cantidad de cada CFC y el SF6 en la muestra.

Veamos la sección vertical que se obtuvo en 1992 de CFC-11 en el mismo transecto que estamos muestreando. El eje vertical es la profundidad en metros, el eje horizontal es la distancia recorrida por el barco y los contornos y colores representan diferentes concentraciones de CFC-11 con la mayor concentración en rosa oscuro y la menor en verde oscuro.

Puedes ver que el Agua Antártica Superficial (AASW, por sus siglas en inglés) es la masa de agua con la mayor concentración de CFC-11 mientras que la Agua Profunda Circumpolar Inferior (LCDW) es la que tiene menos. Podemso decir que la AASW es la masa de agua más joven, LCDW la más antigua y la AABW está entre las dos en edad. Te recuerdo de la edad de las masas de agua es dada por el tiempo que ha pasado desde la última vez que estuvieron en la superficie del mar. Esto es consistente con muestra idea de como se genera cada una de estas masas de agua. La AASW es muy fría y poco salada porque se produce en la superficie por el deshielo veraniego (ver diario del 9 de marzo) y tiene la mayor concentración de CFC-11 porque todavía está en contacto con la superficie del mar. La AABW, fría y poco salada, se produce con el congelamiento de aguas superficiales en invierno, y la que está en el fondo se produjo hace tiempo. La LCDW relativamente cálida y salada, se produjo en el Atlántico hace cientos de años, or lo que tiene muy baos valores de CFC-11 (recuerda que esta masa de agua se produce con la mezcla de Agua Profunda del Atlántico Norte con otras aguas más jóvenes en la Corriente Circumpolar).

Resultará interesante comparar esta sección con los datos que estamos obteniendo ahora para ver los cambios en 20 años. ¿Qué crees que encontraremos?

Detectores de humo y el Instrumento Captura-Electrones

Los detectores de humo utilizan un elemento radioactivo, el americium, que emite partículas alfa y un sensor que las detecta. Las partículas alfa están hechas de dos protones y dos neutrones. El detector de humo activa la alarma cuando algún gas se coloca entre el sensor y el material radioactivo bloqueando el flujo de partículas alfa. Las partículas alfa son muy pesadas y son bloqueadas fácilmente or el humo y vapor de agua.

El instrumento captura-electrones utiliza un isótopo radioactivo de nickel (Ni-63) que emite partículas ß (beta) en vez de partículas alfa. Las partículas ß son electrones emitidos por el núcleo de un átomo cuando un neutrón se convierte el protón y electrón. El instrumento tiene un sensor que detecta y cuantifica el flujo de electrones. El sistema funciona con compuestos que tienen halógenos. El cloro y el fluor son dos halógenos. Lo que distingue a los halógenos de los otros elementos es que cada átomo requiere un electrón para se estable. La necesidad es muy fuerte, por lo que los halógenos tienden a robarse los electrones de dónde se pueda. Es por esto que el cloro puro es tan peligroso para nosotros; nos quita nuestros electrones.

Los halógenos en el instrumento atrapan los electrones de las partículas ß. El sensor puede detectar cuantos electrones fueron atrapados, lo que se traduce en la cantidad de compuestos halogenados, los CFC y el SF6 en este caso, que pasaron en una muestra.

Comments