We are very sad to receive news from Japan's terrible earthquake. Our thoughts are with the Japanese as they try to bring normalcy to their lives. It took less than a minute for hundred of thousands of people to enter a new devastating reality.

We are floating away in the Southern Seas somewhat disconnected from the world. We have e-mail contact as well as a wonderful satellite phone, the morale phone, to keep in touch with loved ones. We get a couple of short daily summaries from the NY TImes and USA Today, so even though we are partially isolated, we do not escape the grip of news like the ones from Japan.

One of my cabin mates is married to a Japanese woman who was in Tokyo during the catastrophe. She and her family are doing well, but it is hard to imagine what they will go through in the coming months. Best of luck for all of them.

As you have heard, the earthquake produced a tsunami whose effects where felt on the coasts of North America (Canada, USA and México). I have been asked through our forum if we felt the effects of the tsunami here at sea. We have not, and there are a couple of reasons for this. I will attempt to describe the basic physics of a tsunami. For that, we need to understand the basics of water waves because a tsunami is a wave that propagates on the surface of the water. Please let me know if these mini lessons are welcome in the journal and if they are too simple or too complicated.

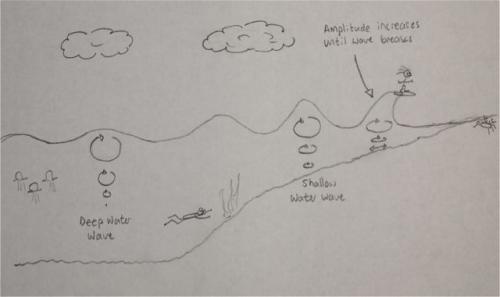

As a wave passes by, water particles at the surface move in a circular way: up, forward, down and backwards, to return pretty much to where the motion began. Next time you are on a beach, either on a lake or the sea, find a bird floating on the water and see that they move just like that: up, forward, down and backwards.

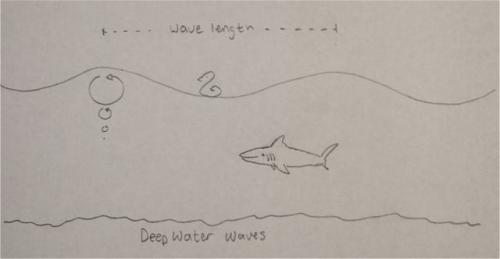

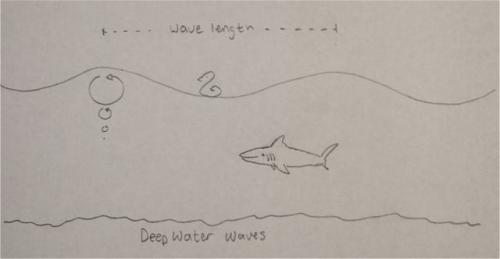

This motion diminishes with depth. Particles just below the surface move in smaller circles than the ones on the surface. The circles are smaller and smaller until we reach a depth level in which there is barely any motion. The depth at which there is barely any motion is roughly 1/6 to 1/7 of the length of the wave (the length of the wave, or wavelength, is the distance between two crests, see drawing below). We call these waves 'Deep water waves'.

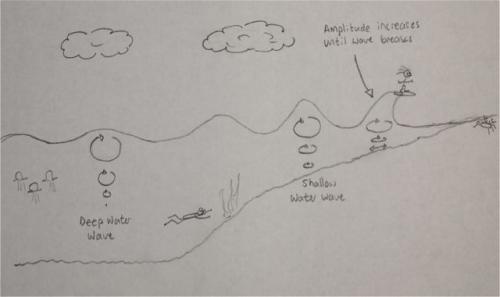

When the depth of the water is 6 to 7 times smaller than the length of the wave, the water particles in contact with the sea or lake floor are still moving; they no longer move in circles but in ellipses. The waves change by the interaction with the floor. Oceanographers call these 'shallow water waves' and say that the waves feel the bottom. The waves reduce their speed as the depth decreases. They end up contracting in length, which forces them to grow in the vertical (increase in amplitude). If the depth continues to shallow, the waves keep growing until they can no longer stay vertical and break. These are the breaking waves that you see on the beach that surfers love.

How can we know if waves feel the bottom? By comparing their length to their depth. As I said before, if the depth is about 6 or 7 times smaller than the length of the wave, then the wave is a shallow one. Let us take a quick look at what type of waves we find in the oceans in general.

The dominant open ocean waves have a length of 150 m. These waves remain deep water waves until they reach a depth of about 25 meters (25 m = 150m / 6). Most waves on the beach on a day without big swells will feel bottom at a shallower depth. Scuba divers know that on a day with no big swells they need to go below 30 or 40 feet (10 to 13 m) in the Pacific Ocean to avoid wave motions.

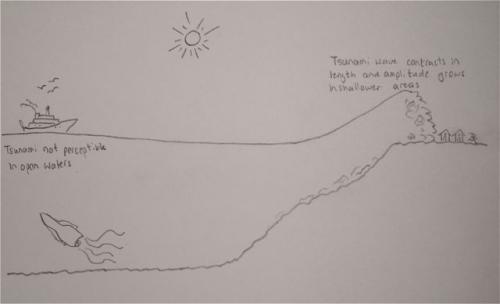

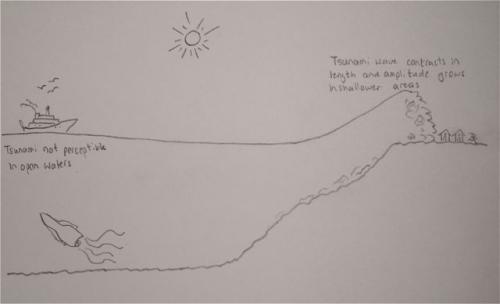

Tsunamis are shallow water waves even when the water depth is 5 km (about the average depth for the Pacific Ocean) because they can be 100 km long. They are very long, but have a very small amplitude when found in open waters. Tsunamis, which means 'harbor wave' in japanese, are extremely destructive in coastal areas because their amplitude grows as the depth decreases, like regular ocean waves. The difference is that they contract in length a lot more, therefore their amplitude increases a lot more, reaching tens of meters. How much they increase in amplitude depends on the local bathymetry. They might grow a lot more in a certain bay than another near one.

There are two reasons why we would not be able feel the tsunami where we are. The tsunami generated in Japan propagated mostly towards the east, no the south were we are. And even if it had come this way, it was so long and flat in open waters that we would not have felt anything. That is why the tsunami alerts tell people to take their boats into deeper waters, where tsunamis are not destructive.

You have heard that the tsunami crossed the Pacific Ocean at the speed of a jet liner. How can a wave move so fast, when the ones we see on the beach move so much slowly?

Deep water waves move at different speed according to their lengths (in science talk this is said to be a dispersive wave). The longer the wave the faster it moves. On the other hand, all shallow water waves move at the same speed in the same depth (non-dispersive), since their speed depends basically on the depth of the water (the speed also depends on the gravitational force, but gravity is essentially constant along the oceans. For the mathematically inclined: v = √(gh), where v = speed, g = gravitational acceleration, h = depth of water and √ = square root).

Any shallow water wave at 5 km of depth, using round numbers, will move at 220 m/s (v=√(10m/s2 * 5 000 m) = 223 m/s). That is a very large speed! We can transform this speed into something we are more familiar with : 220 m/s ≈ 800 km/h ≈ 500 miles/h. The Pacific Ocean is deeper than that in many places where tsunamis travel even faster.

I hope this helps you understand a little bit more about tsunamis. I wish I had note been compelled to write about tsunamis in the journal, because it would mean that that there would not have been such a strong earthquake in Japan.

Sobre Tsunamis

Recibimos con tristeza las malas noticias sobre el terrible terremoto en Japón. Nuestros mejores deseos para la gran cantidad de gente que intenta recuperar la normalidad. Les tomó menos de un minuto encontrarse en una nueva y devastadora realidad.

Nosotros seguimos flotando en algún rincón del Mar del Sur un poco desconectados del resto del mundo. Tenemos correo electrónico, asei como teléfono satelital, llamado el telefono de la moral, para mantenernos en contacto con nuestros seres queridos. Además recibimos resúmenes de un par de diarios, el NY Times y el USA Today, así que aún cuando estamos un poco aislados, no podemos escaparnos de noticias como estas.

Uno de los chicos con los que comparto el camarote está casado con una chica japonesa. Ella estaba con su familia en Tokio el día del temblor. Afortunadamente se encuentran bien, pero cuesta trabajo imaginar lo que vivirán en los meses por venir. La mejor de las suertes para todos ellos.

Como ya has oído, el terremoto causó un tsunami que llegó a afectar las costas de América del Norte (Canadá, EU y México). Alguien me preguntó en el foro si nosotros habíamos sentido el tsunami acá en el barco. No lo hemos sentido por un par de razones que me planteo explicar aquí. Para entender una de estas razones, es necesario entender los fundamentos básicos de las olas, ya que los tsunamis no son más que ondas que se propagan en la superficie del agua. Por favor díganme si estas mini lecciones no son bienvenidas en el diario este, y si les parecen muy sencillas o muy complicadas.

Cuando una ola pasa, las partículas en la superficie del agua se mueven describiendo un círculo: hacia arriba, adelante, abajo y atrás, para regresar a casi el mismo sitio donde empezaron. Puedes ver esto la próxima vez que vayas a la playa. Ubica un pájaro flotando en el agua y vele describir el círculo al pasar una ola.

El movimiento circular disminuye con la profundidad Las partículas justo debajo de la superficie describen un círculo menor que las que están en la superficie. Los círculos se van haciendo más pequeños hasta que se llega a una profundidad en la que las partículas casi no se mueven. Esto ocurre a un profundidad que es 1/6 a 1/7 de la longitud de la ola (la longitud de la ola es la distancia entre dos crestas, mira el dibujo de abajo). A estas olas se les llama 'olas de aguas profundas'.

Cuando la profundidad es 6 o 7 veces menor a la longitud de la ola, las partículas en contacto con el fondo siguen en movimiento, pero ya no lo hacen en círculos sino en elipses. Las olas se modifican mediante la interacción con el fondo. Los oceanólogos le llaman a este tipo de olas 'olas de aguas someras', y dicen que las olas tocan o sienten el fondo. Las olas disminuyen su velocidad al llegar a aguas más someras. Acaban reduciendo su longitud, lo que las obliga a crecer en la vertical (aumentan en amplitud). Las olas se vuelven inestables cuando la profundidad continúa disminuyendo, y acaban por romper. Estas son las olas que vemos en la playa y que los surfistas tanto quieren.

¿Cómo se sabe cuando toca fondo una ola? Al comparar su longitud con la profundidad del agua. Como dije antes, si la profundidad es cerca de 6 o 7 veces menor que la longitud de la ola, entonces las olas han tocado fondo. Veamos que tipo de olas son más comunes en el océano.

Las olas dominantes en mar abierto tienen una longitud de 150 metros. Estas olas se mantienen como olas de aguas profundas hasta que llegan a una profundidad de 25 m (25 m = 150 m / 6). La mayoría de las olas que vemos en la playa cuando no hay un swell grande sienten fondo en aguas más someras que los 25 m. Los buceadores autónomos saben que en las costas del Pacífico hay que sumergirse por debajo de los 10 o 13 metros para evitar el movimiento causado por el oleaje.

Los tsunamis son olas de aguas someras aún cuando viajen sobre unas profundidades de 5 km (el promedio aproximado del Océano Pacífico), ya que pueden tener longitudes que superan los 100 km. Son muy largas, pero tienen una amplitud muy pequeña cuando están en alta mar. Los tsunamis, que significa 'olas de puerto' en japonés, son extremadamente destructivos en zonas costeras porque su amplitud crece conforme el agua pierde profundidad, como cualquier ola de aguas someras. La diferencia es que los tsunamis se contraen mucho más en la horizontal, lo que hace que crezcan mucho más en la vertical, alcanzando decenas de metros. Que tanto crecerá un tsunami depende de la batimetría local. Pueden crecer mucho en una bahía y crecer menos en una playa cercana.

Todo esto para decir que hay dos razones por las que no hemos sentido el tsunami. La primera es que el tsunami viajó principalmente hacia el este, y no tanto al sur. Aún cuando hubiese viajado hacia nosotros, estamos en aguas con una profundidad tal que el tsunami seguiría siendo muy largo y plano. Es por eso que las alertas de tsunamis dirigen a la gente a poner sus embarcaciones en aguas profundas y no en los puertos.

Seguramente escuchaste en los noticieros que el tsunami cruzó el Océano Pacífico a velocidad de jet. Si los tsunamis son olas como las demás, ¿cómo puede viajar tan rápido si las olas en la playa van much más lentas?

Las olas de aguas profundas se mueven a diferentes velocidades de acuerdo con su longitud (en idioma científico se les llama dispersivas). Las olas más grandes se mueven a una mayor velocidad. Por otro lado, todas las olas de aguas someras se mueven a la misma velocidad mientras se encuentren a la misma profundidad (ondas no-dispersivas), ya que su velocidad depende esencialmente de la profundidad del agua. En realidad la velocidad también depende de la fuerza de la gravedad, la cual es básicamente constante a lo largo del océano. Para los que les gustan las matemáticas, la velocidad de ollas de aguas someras se calcula: v = √(gh), donde v = rapidez, g = aceleración gravitacional, h = profundidad del agua, y √ = raíz cuadrada.

Cualquier ola que sea somera a 5 km de profundidad, utilizando número redondos, viaja a 220 m/s (v=√(10m/s2 * 5 000 m) = 223 m/s). ¡Es una gran rapidez! Convirtámoslo en unidades más familiares: 220 m/s ≈ 800 km/h ≈ 500 miles/h. El Océano Pacífico alcanza mayores profundidades en algunos sitios, por lo que el tsunami puede viajar incluso más aprisa.

Espero que esto te ayude a entender un poco más a los tsunamis. Quisiera no haberme interesado en escribir sobre tsunamis en este diario, ya que eso significaría que no habría habido un temblor tan grande en Japón.

Comments