High above the sea on the cliffs at Zapadni Dip or as we call it "Zap Dip", we get to observe the ebb and flow of life around the edge of the southern Bering Sea. Each day that we come out on our watches at the murre colony our job is to record data about the feeding by the parent birds to their hungry offspring.As the days have turned into weeks, we have seen some of these chicks grow and develop and leave the nest. Others are not so fortunate. A turn of events that to our eyes, seems so random as a squabble by two neighboring birds that results in a chick or an egg getting knocked from the narrow ledge to the pile of rocks below. The invariable result? A meal for the Arctic Foxes that patrol the rock piles waiting for just such an event to occur.

While it may seem sad to us to lose young birds this way, it is part of life on a murre colony as it has been for thousands of years. Some chicks fledge, some don't make it. From a scientific perspective, we should think about what we are seeing happen on that colony. Each day the parent birds are making foraging trips, sometimes close to the island, perhaps at other times out near the "shelf" a steep underwater drop off into the Pribilof Canyon. When they make these trips they are either looking for food for themselves or for their chicks. Typically the birds are eating small fish, Euphausiids (krill) and occasionally squid or other mollusks and some crustaceans.

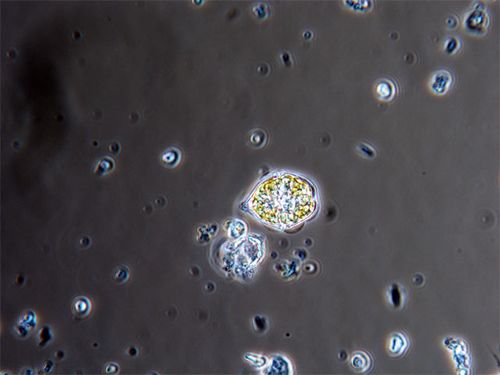

These prey items that are being eaten by the murres had themselves, been very busy devouring smaller creatures such as copepods and other zooplankton, which in turn are eating even smaller zooplankton or phytoplankton. The phytoplankton absorb various nutrients from the seawater and use energy from the sun to live and to grow. The Bering Sea is a very productive environment that is rich with these microscopic organisms.

In other parts of Alaska, the salmon play a very important role in the transfer of nutrients from the ocean up into the watersheds. As the salmon spawn and move up into the tributaries, they are eaten by things like bears and other predators. The salmon carcasses scattered about the ground and the waste from the bears provide needed nutrients for the different plant species that support the web of life on the mainland of Alaska. Here in the Pribilofs, the seabirds and the fur seals play a similar role in the transfer of energy from the Bering Sea onto the islands, where small, but very complex food webs occur.

I remember one day standing near the bottom of a group of cormorant nests and noticed the piles of waste being mined by beetles and other insects. These "processed" nutrients from the sea are being used by terrestrial insects, which might become food for the Pribilof Shrew, which in turn might be eaten by the Arctic Fox.

On just one night on my watch I had the good fortune to witness three different events that prompted the writing of this journal entry. The first, an obviously sick or injured Thick-billed Murre was sitting near the edge of the water down below. Not too far away there were a couple foxes sniffing around for fallen eggs or chicks. While I was there until late that night and the bird was hanging on, by the next morning there was no bird present at that spot. What did this event mean? A boon perhaps, for a fox that hadn't had a meal for a couple of days? A tragedy for the bird's chick waiting back at the nest? Or maybe a lucky day for the fish that would not get eaten by a murre that night?

Later that evenig, a short distance out in the ocean, a small pod of Orca whales passed back and forth within my field of view. Within parts of their range, there are populations of Orcas that don't travel very far. These whales staying fairly close to the place that they were born and feed mainly on salmon and other large fish that they often catch by working cooperatively as a group. Other populations of Orcas are more transient, ranging far and wide thoughout the ocean. These whales are feeding mainly upon marine mammals such as larger whales and seals. The group of Orcas working the seas around St. Paul Island are likely searching for Northern Fur Seals as a meal. These large seals would provide the Orcas with a valuable source of fat to provide the needed fuel to keep them alive and healthy in the cold Bering Sea. It took many trips out to the fishing grounds for the seals to build up those fat reserves in the first place, again think transport and transfer of energy.

My last observation of the evening was quite a thrill. Since we'd started our nest observations, I'd noticed how much larger the chick in nest #22 was in comparison to others nearby. Although it appeared to be about a third of the size of its parents, it was fully feathered and seemed to grow larger by the day. On this particular evening, chick #22 decided to jump. It leaped from the nest and was escorted down to the water by its father as it half flapped, half glided its way down to the Bering Sea. I saw it paddle alone, out to a calm stretch of water, away from the waves that were breaking on the shoreline. A few minutes later, it was joined by its father and together they swam on out to sea.

Most birds don't leave the nest until they are about ready to fly and to find their own food. Murres are somewhat unique in their chick rearing strategy. The fledglings leave the nest and hopefully reach the water in that desperate jump that they make. If they do reach the water, the male bird provides care for the youngster at sea for a period of time until the young bird can catch dinner on its own.

It was quite a thrill to see that young bird fledge. Even though we are watching these birds diligently, it was an event that could be easy to miss if you happened to glance down to record some field notes or otherwise had your eye off of the colony. I was fortunate to see that little bird successfully negotiate that airspace over the rocks and the foxes down to the safety of the sea. Whether we live in the Chesapeake Bay region or out here in the Bering Sea, if we look carefully at the natural world, and pay attention to the relationships that exist within it, we can see that everything is connected and has a place within the web of life.

Comments