At the end of most days I find myself in the dining hall. It's the social hub of camp, warm, a great place to write, and has a spectacular view of the Brooks Range. Many nights as I'm winding down, two people are drinking coffee and just starting their day. Trevor and Adeline head out to the field while most of us sleep. The duo from the University of New Mexico spends every day from 2:00 AM until 10:00 AM observing birds. After learning about what they do, I was eager to join them in the field.

After a short nap and throwing some gear in my pack, I met up with Trevor and Adeline in the dining hall. Trevor is a Ph.D student, and Adeline is an undergraduate research assistant studying biology at UNM. Prior to heading out to our trucks, I asked Trevor to explain what he does. Trevor uses data collected by volunteers from the North American Breeding Bird Survey, and the Christmas Bird Count. "Most of what I do involves sitting in front of a computer," Trevor explained.

This summer Trevor and Adeline are counting absolute abundances of birds at study sights here at Toolik (arctic tundra), and south in Fairbanks (boreal forest) to compare energy flow in different bird communities. What they are essentially interested in is the comparative energy use of migrant birds vs. resident birds in different areas. Trevor explained that as you move north, more resources get used by migrants than residents. For example, Florida's birds are primarily resident species, as you move north towards Canada you find more migratory species. He further explained that from the boreal forests north into the arctic tundra as much as 70-100% of the resources are used by migratory birds. I later read that only 11 species of bird can live year-round in the arctic, while the migrant birds in the arctic consist of nearly 90 species!

The first step in the bird team's study is to find out what species of birds are up here, and how many there are. Then the team uses the body size of birds to estimate their energy use (bigger birds would use more energy). As the clock approached 2:00 AM we loaded our packs into trucks. I opted to drive separately so I wouldn't have to stay out the entire night. I was relieved to not have to put my usual rubber boots on after a long day of work in the field already and chose to wear my hiking boots. I would later learn that this was a mistake.

We drove north on the Haul Road to Imnavait Ridge, next to the site of the Weintraub Team's plots described in my June 9 journal entry. Tonight's observations would be made on one of 4 plots. Each plot is 1 square kilometer in area with 16 evenly spaced observation points. With the help of a GPSA Global Positioning System (GPS) is a satellite-based navigation system used to track the location or position of objects on the Earth’s surface., we hiked down the valley to the first observation point. The team sits quietly for eight minutes at each point, noting the calls they hear and trying to get a visual confirmation of each bird. These eight-minute observations are called "point counts." Within seconds, Trevor and Adeline are identifying bird calls that I can't even here. They are so accustomed to making these types of observations that they seem to be picking up on subtle things that I don't normally notice. In contrast, Adeline mentioned that she hadn't noticed any spiders running around the tundra, while I can't help but notice them everywhere.

Although the sun remained low on the horizon, it was slowly working its way back up. Walking to our first point we saw three very noisy and very busy Jaegers. These playfull birds have been described as "carnivorous pirates," as they are known for steeling food from other birds. Despite the nickname, it should be noted that they are also skilled predators in the tundra. Unfortunately I obtained virtually no good bird pictures on this outing. I quickly realized that birding is much more fun with binoculars, and chose to put down my camera to pick up a pair.

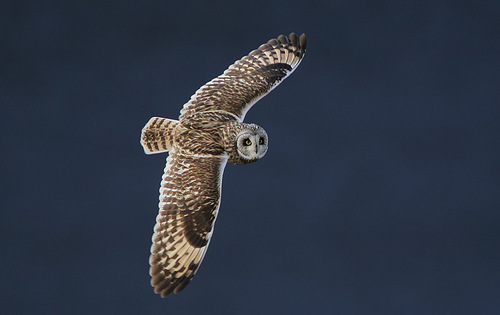

Walking to our second point we came very close to a Northern Harrier who quickly shot up out of the tundra, and seemed less than pleased by our presence. Trevor quickly identified this large raptor as a male, and later spotted a female. It was amazing to watch Trevor and Adeline debate if they were hearing the call of two separate birds until they spotted the second Harrier. Shortly after, Trevor pointed out what turned out to be my favorite bird of the evening. Peering through the binoculars, I watched a Short-Eared Owl soar across the tundra and land in front of a small boulder.

I tried my hand at recognizing the call of the more common birds like the Golden Plover, and the Savannah Sparrow, but by far the most abundant bird in the area is the Lapland Longspur.

After several point counts, I decided it was time to make my way back to the truck. I thanked my hosts and slogged through the tundra towards the truck. I displayed far less skill avoiding streams and low points than when Trevor and Adeline were leading the way. About half-way to the truck I realized that I did not know the gate combination to the access road to get out of our research area. By this point the bird crew was further off, but the low-angle light of the sun at that time of night made some amazing colors on the tundra so I enjoyed the views. After getting the combination and making a second attempt at traversing the bird observation plots, I was warm behind the wheel of the truck. I arrived back at camp at 4:30 and was thankful for an opportunity to sleep in.

I dried my soggy feet, caught a good night's sleep, and met up late with Team Spider to finish off our Friday with some work around the lab and another check of our pitfall traps.

Comments