Ending the Experience but not the Momentum

It’s been three weeks since my Alaskan expedition ended. On Friday, June 25th, I made my way down the Dalton back to Fairbanks (a quite uneventful trip down the Dalton, might I add) where I then began my journey home the next day. Two long flights and a short drive got me home to see my family in Alabama, and two days later I drove the 16 hours back up to NYC.

Over the past weeks, I’ve been mulling over summarizing the experience, as this summary journal was due to be posted quite a while ago. The first week back I asked myself “How does one adequately summarize a life changing adventure?” To which, I’m not sure I ever found the answer although I have now written something as I am posting it for your reading pleasure today.

But more recently I’ve begun to think about how summaries feel like “the end”. You know, “I finished the book, and here’s what it was about”, “Here’s what we learned today in class”, etc. When the experiences are really fun and energizing, endings can be hard, so in writing this blog, I have a newfound respect for my students who struggle to summarize their learning at the end of a fun day of class. It’s also hard when there is no obvious end. I have left Toolik, but the work I was doing started before I got there and is continuing now and will continue, with any luck, for many years.

All that being said, I’m going to try and focus this blog on the momentum I’m carrying with me through summer and then into the classroom this fall. This, of course, is not actually an ending, but a new beginning for me as I can now utilize my experiences to build stronger lessons this upcoming school year.

Science is Messy

This was perhaps the most spoken theme of the trip, and also the fallback phrase to summarize anything that wasn’t perfect… especially when it comes to method development and/or data collection. Would we like to measure NDVI of a plant in situ right before and right after it rains? Yes! Are we likely to be able to get those measurements and hold all the constant variables constant? No. #scienceismessy! Oops, I missed that tram time! Well, I’ll just make a note and write down the time that I noticed. #scienceismessy!

And while it seems like an easy catchphrase, it actually is a very delicate and complex idea, which requires a lot of confidence (developed over years of experience). As a group, when something began to get messy, we often discussed options for “limiting the mess,” looking to one another to gain that necessary confidence, before falling back on “oh well!”

For science teachers, there’s always a struggle to create lessons and labs that are realistic enough to showcase how messy data collection (and the data itself) can be, while being clear cut enough to support students in their understanding of the concepts we’ve been studying. I think most science teachers would recognize that as important as it is to know and understand the theories being taught, developing that sense of self-confidence during “messy” or “real” data collection or analysis is just as critical.

For myself, as a chemistry teacher, developing authentic “messy” science for my students can be extra daunting due to the higher level of safety precautions that are often required. But I think I’m coming to realize that at least talking about it is important, including stressing where precision is (or is not) important and valuable. For example, it’s generally important to measure out as close to 0.23 grams of the reactant (if that’s what is specified), but you don’t need to have exactly 750 mL of water in the water bath you create.

I find myself thinking now about the distinctions between lab-based sciences and field-based sciences and how developing this sense of confidence differs between the two. I found that for myself it feels easier to be confident in allowing messiness to exist when I’m in the field versus when I’m in the lab, which seems to make sense. It’s easy to write off things like humidity and temperature when you have little room to control them. I wonder now how miniature field experiences for my students may help them to gain this sense of maturity in their own scientific endeavors.

Science is Collaborative

I learned pretty quickly before my trip that it can be hard to explain what exactly Toolik Field Station is to those who are unfamiliar with the idea of a “research station”. “Remember, it’s not a town! I can’t buy anything there!” I would constantly remind my students as they came up with packing lists for me based on the Alaskan ClimateThe average weather over a particular region of the Earth. Climate originates in recurring weather phenomenon that result from specific types of atmospheric circulation..

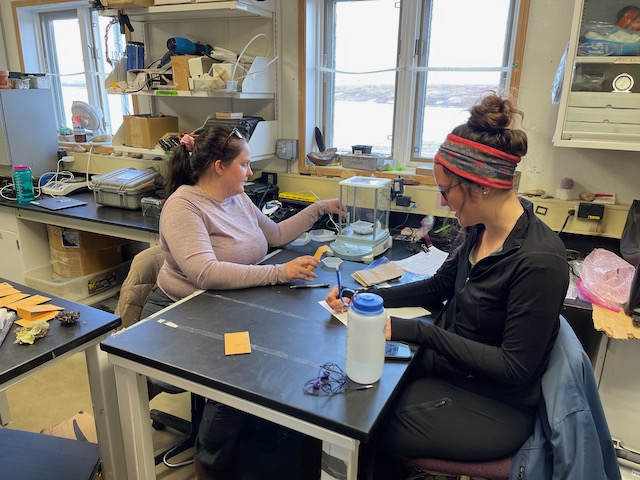

Although Toolik isn’t a town or even a village (although I’m not entirely sure what the definition of a village is), it is definitely a community, complete with many individuals such as scientists from varying groups across the country and essential staff who make sure the camp (and the humans in the camp) are functioning safely. And the best thing about this community, to my delight, was how on board everyone was with assisting everyone else, and how much interest everyone had in each other’s work.

I’ve spoken before about the sciences being interdisciplinary–that biology bleeds into chemistry, which bleeds into physics (and back). And while this was definitely evident at Toolik, what was even more evident was the need for scientists to have skills outside the science field in general. I don’t know if I can count all the times we went into the workshop for “arts and crafts,” where we would fashion a clamp for an instrument or build a buffet table to place berries on.

I think it’s important also to note here that there are so many pieces and roles that are important to make sure that science research is able to be done, and there are so many people that fit into those roles. I think often people think to be involved with science means that you have to be someone who comes up with projects, collects data, analyzes data, and writes and publishes papers, but that just isn’t true. There were many people who worked at Toolik who solely were there to collect data to be published elsewhere. There were people who worked in roles to support the scientists. And those roles and collaborations are just as vital to having the research complete as the scientist themselves.

Science is joyful!

As I wrote the title for this last theme, I started laughing because there were so many times that science was rather irritating (as opposed to joyful) on the trip: having to postpone tram runs over and over due to the weather, accidentally unplugging the Jaz spectrometer during set up and having to start all over, having voles eat all our thaw depth markers, etc. To be clear, there is a great range of emotions while doing science, and in field science in remote areas, where you have even less control over what you’re doing, the range grows even broader. So in writing “science is joyful”, I’m definitely not trying to negate the angers and frustrations science can bring—they are ever-present (and will forever be).

But, if you’ll allow me to get slightly philosophical, there’s something joyful in having irritations in the process, because it makes for a greater satisfaction when you fix the problem, or if there isn’t a good fix other than time, it makes for a better story in the end. I don’t think field science would be nearly as joyful or fun if everything ran smoothly and perfectly. It also allows the joyful times to be even more joyful than otherwise.

There’s a uniqueness to the joys of field science however. Being able to tell my family and friend I “escaped” a grizzly bear, while not joyful during the experience, is something I will always hold with me. Remembering how every day it wasn’t cloudy I took the same exact picture of the mountains because it was just so beautiful. There’s something fantastical about being in such a beautiful location, despite the irritations (and mosquitos).

Now that I think about it, I guess lab science has its ups and downs, as well. Though they don’t usually involve grizzly bears.

- < prev

- 24 of 24

Comments