Data Collection Continues

Both yesterday and today we spent long and productive days on the fjord. The weather was gorgeous today! It was around 8°C (46°F) with very little wind and bright sunshine. We spent most of the day doing bathymetry (mapping the seafloor) which is very slow work, but with weather like this it was so pleasant to just be out on the water.

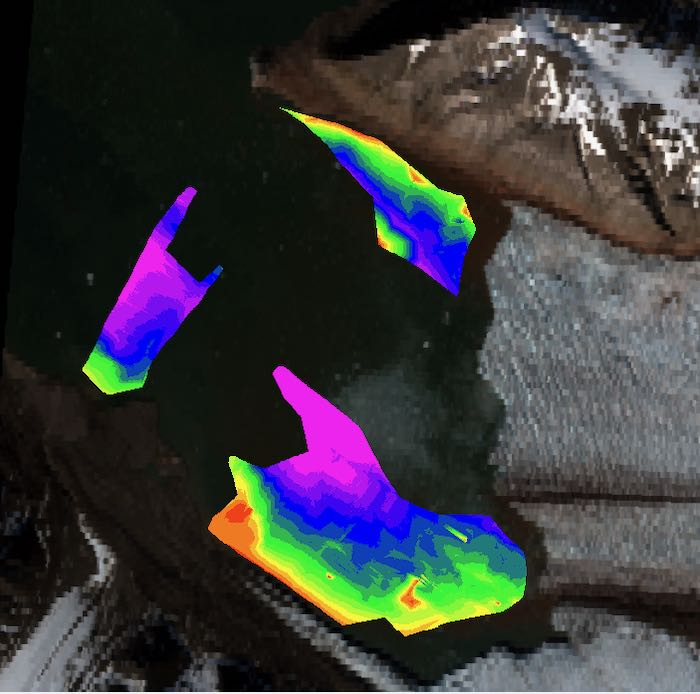

The seafloor is taking shape

The bathymetry work is really coming together. As of yesterday we had mapped three pretty large sections in front of Kronebreen and Kongsvegen Glaciers. Here’s a preliminary image of the data so far. You’ll notice a large section in the middle that we haven’t been able to map yet - that’s because it’s almost always chock full of icebergs that we can’t drive through!

Seeing the map emerge is really amazing. Although it’s depressing to realize that this area is newly exposed because of the rapid retreat of the glaciers (because of climate change), it’s interesting to realize that we may potentially be the first people to map some of this part of the ocean floor.

Awaiting the surge

We’ve been monitoring a large upwelling plume in front of Kongsvegen, that another research group here has also been watching carefully. They are interested in how glacial lakes drain, and there is a huge lake forming way up on the glacier which has not yet drained. If it does so in the next week, we’ll be watching that plume to see if that’s where the water will flow out. Where that spot is, looks like a cave that seems ready to collapse!

On to Kongsbreen

Our work today was in front of the third glacier in our study area, called Kongsbreen GlacierA mass of ice that persists for many years and notably deforms and flows under the influence of gravity.. This glacier is smaller, and not as active as the other two, and much of the glacier is now grounded on bedrock above the water level. But it is still flowing forward, releasing plenty of sediment from a few different plume areas, and calving off icebergs. In fact, while we were there we witnessed a pretty spectacular calving event, which I was super lucky to capture on video!

Just like the other two glaciers, it’s quite notable how much the glacier has receded since I was here ten years ago. I don’t have great photos from this area from 2011, but I’ll work on trying to illustrate this in a future post.

I had some time to do a little drone flying today, which allowed us to view in more detail how water is flowing under Kongsbreen GlacierA mass of ice that persists for many years and notably deforms and flows under the influence of gravity. to create the sediment plumes. You can see how the sediment comes way out into the fjord in the picture below. To get the vantage point I wanted, Xander and I got out on the amazingly beautiful island of Colletthøgda between Kronebreen and Kongsbreen Glaciers, and then hiked up about 100 meters up to look over the glacier. (If you’ve been following my blog, last week when I had to do an emergency landing, it was on the other side of this island.

Looking back in time

I was also able to do some flying on an island across from Kongsbreen GlacierA mass of ice that persists for many years and notably deforms and flows under the influence of gravity. that has only recently covered in glacial ice (less than 20 years ago). Although it’s depressing to realize how much ice has been lost, it’s another opportunity to visualize features that glaciers leave behind. Again it makes me think of what the Boston area probably looked like at the end of the last ice age, around 15,000 years ago!

Check out this video I made from the drone footage I took today. My 7th graders might recognize the terms glacial erratics, glacial scarring and kettle ponds, all of which are visible in this video. Also visible are really interesting features called thrust ridges, which are deposits of sediment left behind when different sections of the glacier push up against one another and concentrate the deposits. You can see a cross-section from Kongsvegen GlacierA mass of ice that persists for many years and notably deforms and flows under the influence of gravity. here, and then you can see the deposits left behind in this photo.

Wildlife Sightings

Yesterday as we were winding our way through the icebergs we saw several large bearded seals! Here is a video compilation that I made of several of our seal sightings.

Comments