In the Dark

For the past week we have been trying to get our final samples of the summer season here in the Dry Valleys. Our last sampling expeditions have been delayed by weather so the last few days have been all in the lab looking to finish up anything we can.

The team has been lightheartedly talking about this part of the data collection for weeks - with a certain ominous subtext. You see, we have taken hundreds of samples this season. We extracted the organisms and identified and counted along the way. Everyone on the team chipped in to get the task done accurately and efficiently. All of this time consuming work has been spread out over time.

In the geo-chem lab, Meredith and Sarah have been taking every one of those samples and completing the chemical tests which tell us the pH, conductivity, and moisture content of the soils. They have spent many late nights running extracts from soils that are going to be packed up and shipped to their university for analysis of nitrogen, salts, organic and inorganic carbon, and metallic ions.

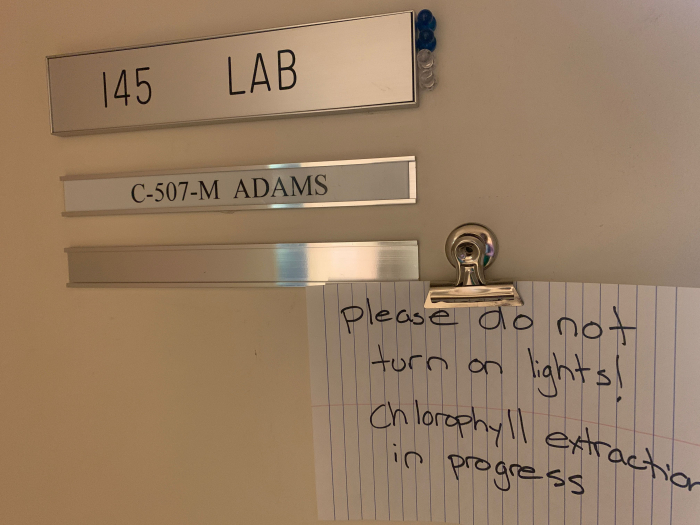

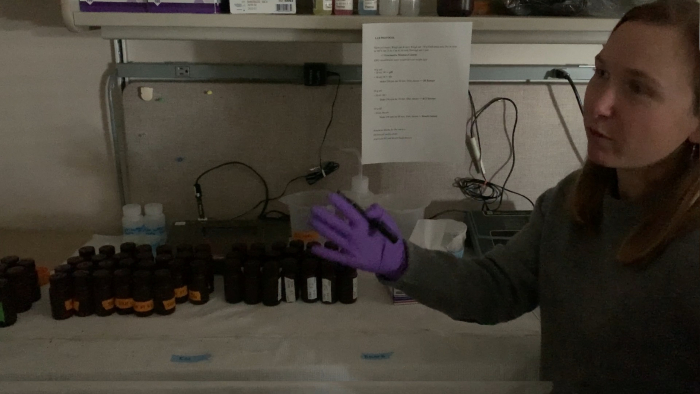

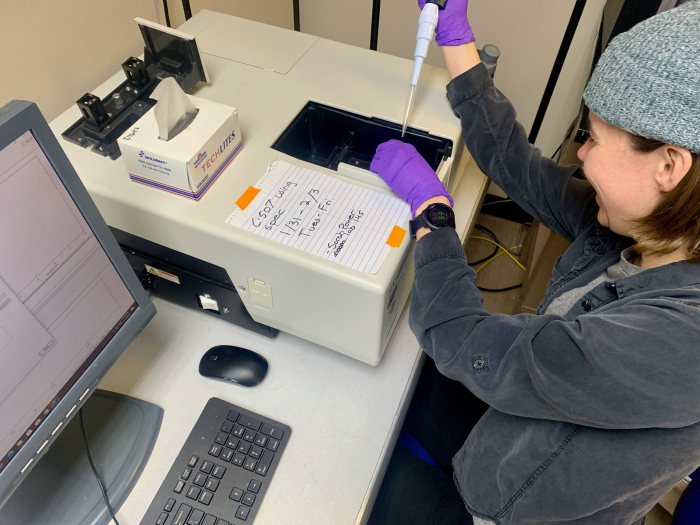

But one test has to be run on a tight, uninterrupted schedule. That means, once we have all the samples, we can start. Along with the complex steps and time sensitive nature, it also has to be done in a light-free environment - aka - the dark.

In most ecosystems, the energy for a food web starts with light from the sun. This light is captured through photosynthesis and used by producers like alga, bryophytes (mosses), and cyanobacteria to make food. These organisms take carbon dioxide from the air and combine it with water and light energy to make molecules that store energy. This is thought to be the source for the carbon that is then used by other organisms to live and grow.

The measurements we are running will tell us how much chlorophyll is in a specific amount of soil. In forests and grasslands this would be insignificant compared to the plants growing above the soil, but in this ecosystem, soil is where the producers live. By measuring the amount of chlorophyll in a soil sample, we can estimate the amount of energy and carbon that is brought into the soil food web through photosynthesis.

One of the biggest questions in the Dry Valley ecosystems is where does the carbon come from. Many studies have investigated the question of where different nutrients come from (or are not coming from). There are lots of gaps in our understanding of how different nutrients move through ecosystems. There is much interest in carbon because it is the building block of all life on earth. It is also a crucial component to greenhouse gasses that control the temperature of Earth itself.

We will never understand every aspect of our ecosystems but our knowledge is cumulative. Each time a new discovery is made here or new understanding is developed from the research, many new questions crop up. These new questions drive the next generation of research. If we can understand how carbon moves through ecosystems better, we can make better models of how the planet functions. Better models shed more light on understanding climate, climate change, and ways to address it. Lots of questions remain for future scientists. As you can tell from the dynamics of our team, there are many young scientists taking up the challenges.

No Groundhogs to tell us the weather

It's Groundhog Day eve in the US as I write this. On Groundhog Day we use the signs of nature to make predictions about the changing of seasons. I wonder what change people would note here in the Dry Valleys. One thing we are all noticing is more cloudy days and a sun much lower on the horizon. Maybe, once we understand the Antarctic nematodes better, they too can have a day celebrating their weather predicting abilities...

Comments