Up, Up and Away (toward Lorne Automatic Weather Station)

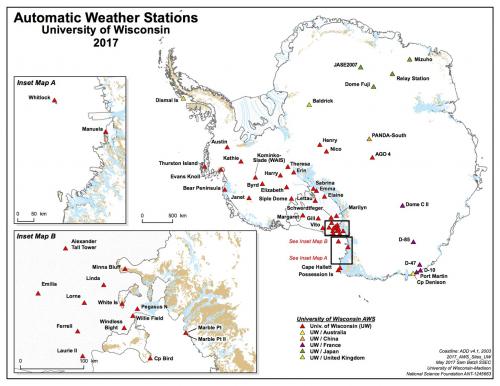

This journal entry is a rather exciting one for me as it describes my first venture to an Automatic Weather Station (AWS). Many of the Automatic Weather Stations in Antarctica are dispersed across the continent and require some means of travel. I have shown a map of the distribution of AWS units across Antarctica in a previous journal post but will also include it here as a source of reference (See Insert Map B).

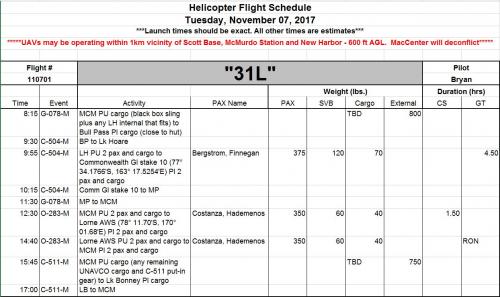

Although there are rare exceptions, no AWS unit is accessible by vehicle and thus can only be visited either by helicopter (for those in fairly close proximity to McMurdo) or by Twin OtterA highly maneuverable utility aircraft developed by de Havilland Canada. It can be flown slowly and in tight circles, and is designed for 20 passengers, short takeoffs and landings, and often used for cargo, passengers, and as a science platform. aircraft (for those a farther distance away). Although we have been on the flight schedule (helicopter and Twin OtterA highly maneuverable utility aircraft developed by de Havilland Canada. It can be flown slowly and in tight circles, and is designed for 20 passengers, short takeoffs and landings, and often used for cargo, passengers, and as a science platform. flights) since I arrived at McMurdo Station, it has generally been disappointing as the flights have not been able to happen. Reasons for this include a low priority on the flight list, inclement weather, and fuel availability. On this day (November 7, 2017), it turned out that we were on the schedule for flights on both the helicopter and the Twin OtterA highly maneuverable utility aircraft developed by de Havilland Canada. It can be flown slowly and in tight circles, and is designed for 20 passengers, short takeoffs and landings, and often used for cargo, passengers, and as a science platform.. The Twin OtterA highly maneuverable utility aircraft developed by de Havilland Canada. It can be flown slowly and in tight circles, and is designed for 20 passengers, short takeoffs and landings, and often used for cargo, passengers, and as a science platform. flight did not occur but the helicopter flight was a go.

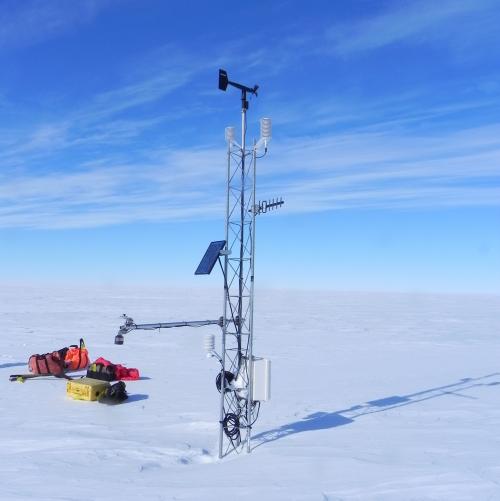

Later that day at 12:30 pm, we would be on our way to Lorne AWS. So, what exactly would we be doing at Lorne AWS and how long would it take? The primary objective of the flight was to reset the modem clock, ensuring that data transmitted from the array of sensors in an AWS unit is stamped with the correct date and time. We had also planned to raise the tower (actually the sensors) by approximately one foot. However, before any of this could be accomplished, we would have to access the power supply or battery box. The battery box is shown in the photo of Lorne AWS at the bottom of the tower, secured in the snow.

For the second question, “How long would it take?” is not as important as the question, “How long would we have at the site before the helicopter pilot had to return to base?” We were given approximately two hours to complete our scheduled tasks. As for every flight planned to an AWS site, preparation and planning are the two most important aspects and require focused attention. Because flights are costly and in high demand, one does not want to get to a site only to realize a tool was left on the on the lab table or the proper sized wrench was not included in the tool kit. Days prior to the scheduled flight, Carol and I were in the lab, going through each of the proposed steps in the process and ensuring that we had the appropriate tools as well as extras of the rather small and easy to drop screws, washers, and other related hardware. However, all of the preparation invested for an upcoming flight does not take into account one very important aspect: the facts on the ground. It had been almost one year since Lorne AWS had been inspected without any visual indication or observations of what the state of the AWS was since that time. Nevertheless, we pooled all of the tools, tool bags, equipment and supplies needed for the upcoming flight, made sure they were all weighed and tagged, and then transported them to the helipad 45 minutes prior to the flight. Everyone who is scheduled for a helicopter flight is required to undergo a safety briefing. In addition, we were fitted with a helmet and weighed prior to being escorted to the helipad. The helicopter we would be flying on was an A-Star helicopter, shown in the photo below.

Both Carol and I got into the helicopter. Seeing as this was my first time in a helicopter, I got to sit in the front passenger seat next to the pilot, Bryan. I was incredibly fortunate to stare out into the Antarctica landscape from a front row seat, taking in the gorgeous views. Below are photos from the helicopter ride.

Of course, there was no way I was going to let this opportunity pass without a selfie with the pilot.

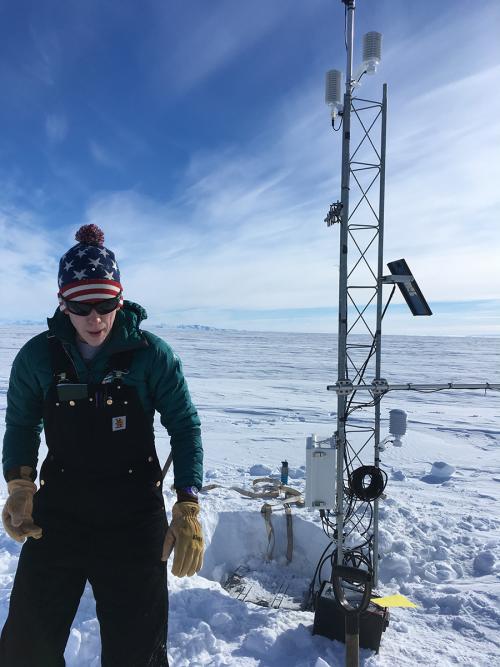

Both Carol and I exited the helicopter and retrieved all of our gear from the storage compartment cage on the side of the helicopter. We then proceeded to the site to begin our work. Below is a photo of Lorne AWS before we started our work.

Do you notice a difference between this photo and the photo of Lorne AWS located earlier in the blog? Yes, you are correct! The Battery Box is not visible in the current photo. It is there – hidden under approximately two feet of snow! This is what we had expected and came prepared with shovels to begin the process of removing the snow and exposing the battery box. We dug until we reached the top of the battery box and then began clearing out the snow accumulated along the sides of the box. Once a trench was cleared, we pulled on the box, hoping it would budge… but no luck. Since the box contains three batteries each weighing 70 pounds apiece, it was to be expected. We opened the box and removed one of the batteries, placing it in an empty battery container, thinking that reducing the weight of the battery box from 210 pounds to 140 pounds would make enough of a difference that the entire battery box could be moved. Again, no such luck. It would turn out that a layer of ice had formed on the bottom of the battery box, creating a significant resistance to our best efforts, posing a challenge that we could not overcome. The tools that would be needed to detach the battery box from the frozen layer would be a smaller shovel to make removing snow from within the trench a little easier and an ice pick to break and remove the ice layer. With the time allotted by the helicopter pilot slowly coming to a close, we secured the site until a future return flight could be arranged to continue the tasks at Lorne AWS.

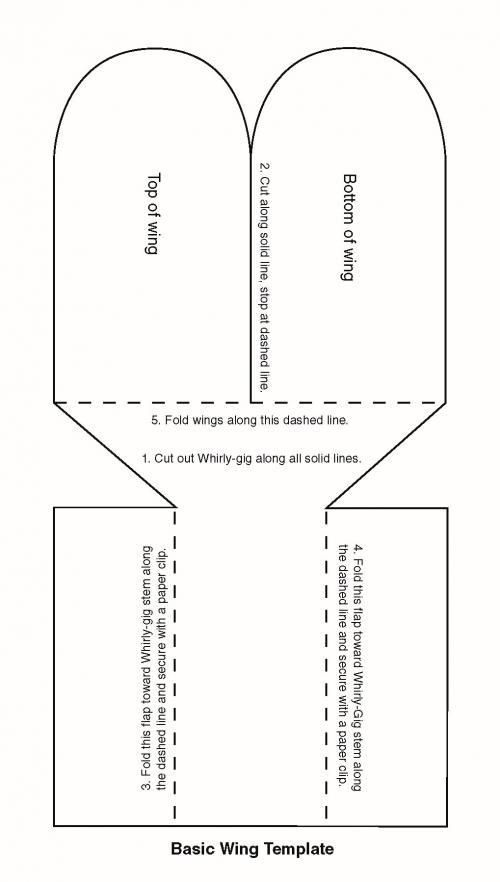

Now that you have read about a helicopter flight, it is time to investigate the falling time of paper helicopters with Anastasia.

Coming Up Next: McMurdo Station in Antarctica is a very small, tight-knit community with less than a thousand residents over a typical summer at any one time. Yes, McMurdo Station is a small world. But I would have no idea just how small that world could be!

Comments