This journal brought to you by:

- Mrs. Garay and her students at Redd School

- Becky Shimp and the 6, 7 and 8 grade students at St. Edwards School

- Amy Bogdal and her 4th and 5th grade students at Shelby Oaks Elementary

- Jane Gillespie and her 6th grade Sparks students

- St. Philomena Junior High

A Closer Look at … a Weddell Seal’s Lungs

As you know, seals are mammals. Do you remember the defining characteristics of mammals?

1) Mammals are warm blooded

2) Young are born alive as opposed to developing inside an egg

3) They have fur or hair on their bodies

4) Every mammal is a vertebrate – they have a backbone

5) Mammals feed milk to their young.

And finally, mammals also have lungs which make them different - than say a fish. In order to breathe, seals have to have access to air, and Weddells do that by using holes or cracks in the ice.

Let’s review how lungs work for mammals

First, mammals (including humans) inhale air, which contains oxygen, through their nose or mouth. That air fills the lungs, which are made of a stretchy tissue that easily expands. The lungs take in oxygen from the air and send it to the blood and store it in a molecule called hemoglobin, to circulate through the body. At each cell in the body, oxygen is exchanged for a waste molecule called carbon dioxide. These waste molecules are carried through the bloodstream back to the lungs where they are expelled every time you exhale….pretty amazing.

You probably already know what bones surround the lungs to protect them – the rib cage. If you push your ribs or chest bones in, will you make your chest cavity smaller? No! And that’s good – those bones are there to protect our important organs. So do you know what muscle helps our lungs expand and compress when we inhale and exhale? The diaphragm! It is a strong wall of muscle that allows air to enter the lungs by moving downward or pushes air out by moving upwards.

So what’s different about a seal?

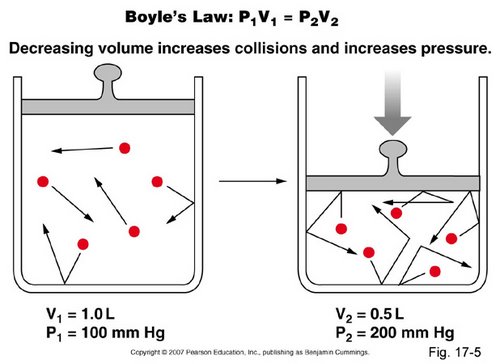

Weddells have a different kind of chest cavity that is a lot more flexible, so that it actually does compress to get smaller. Why do they need that? Because they make really deep dives, and the further down they go underwater, the more pressure there is. When a seal dives, the water pressure forces the air spaces in their bodies to get smaller. Once they dive to about 70 meters deep, the volume of air in their lungs has reduced to about 15% of its original volume, their lungs collapse, and their chest cavity gets smaller.

So where does all that air go? Really, it just gets smaller. There’s a rule in science that says if you have a certain volume of air and you decrease the amount of space it can take up without changing the temperature - the pressure increases. That’s Boyle’s Law. When the lungs collapses, oxygen exchange between the blood and lung essentially stops and the seal must rely on just the blood and muscle oxygen stores.

Have you ever tried to dive to the bottom of a deep swimming pool? How did it feel? Your ears might have felt a pop, or your head might have started to hurt. That’s all from the water pressure. Humans have extra air spaces, like our sinus cavities behind our nose and eyes. Under pressure from deep water, those spaces start to hurt because the water pressure is forcing them to shrink to a smaller space. The good news for seals is that they don’t have any extra air spaces, so it’s not painful for them to dive to great depths!

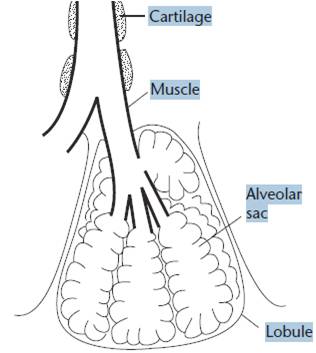

Unlike us, marine mammals have flexible chest walls and specialized structures with allow the tiny air sacs in the lungs, alveoli, to completely collapse followed by the airways to which these sacs are attached. These same structures also allow the lung to reinflate. Aveoli in the lungs are coated with surfactant (a white soapy substance) and seals often cough this up which aids in reinflation after diving.

How does a seal get enough air?

Weddell seal lungs really are amazing! Not only can they compress on a dive, but they are much larger than our lungs, which means they have more space to take in air when they are not diving. Before Weddells go for a dive, they will take several huge breaths to fill their lungs with oxygen. Their lungs send that oxygen to their blood and muscles to be stored for later use on the dive. Then they exhale all the remaining air in their lungs to make it easier for their lungs to collapse on the way down. Think about what you do before you jump in the pool: you probably take a big breath and don’t let it out. You are trying to save the air in your lungs so you can use the oxygen in your lungs while you are underwater, but seals do the exact opposite!

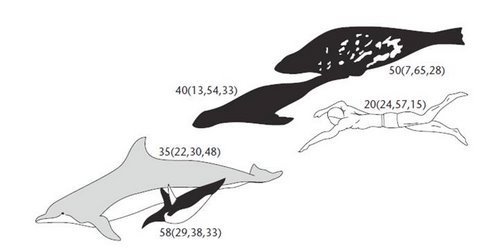

Since Weddell seals collapse their lungs during a dive, what other ways do you think they might be able to get oxygen to parts of their body? Believe it or not, Weddell seals actually store oxygen in their tissues like an internal scuba tank. This ‘scuba tank’ is divided into three compartments – oxygen stored in the lung, blood and the muscle. Diving animals such as the Weddell seal have higher concentrations of oxygen carrying pigments, hemoglobin and myoglobin in the blood and muscles.

How long can a Weddell seal stay underwater?

Typically, a Weddell will dive for about 20 minutes and then come up for air. Dives longer than 20 minutes cause a build-up of lactic acid. Have you ever exercised and felt sore the next day? That’s because your body used all its oxygen and started to produce energy without oxygen by building up lactic acid – this is called anaerobic metabolism. Weddell seals do occasionally dive for over an hour – the longest dive reported for a Weddell is 89 minutes!

How deep to Weddell seals dive?

On average, Weddell seals tend to dive less than 300 meters but occasionally go as deep as 800 meters. Near the coast where the water depths are shallower, they tend to dive to the bottom of the ocean in search for prey. This is, known as benthic diving. However, as the seals travel further from land, the water becomes deeper. You might think that they dive deeper, but they usually don’t. They still tend to dive between 150-300 meters. Because they are not diving to the bottom, this type of diving is called pelagic diving.

Where do Weddell seals go and what do their dives look like?

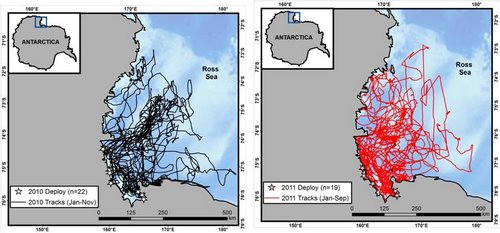

Previously, Weddell seals were thought not to travel very far from the coast. That is why our research is so exciting! The seals we have tagged have travelled over 500 kilometers out to sea near the continental shelf before returning to pup, breed and molt. You can see from the two figures below that the Weddell seals travelled far out to sea during the first two years of the study (2010 and 2011).

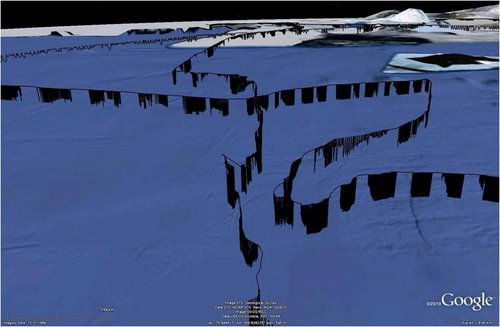

So we can see where Weddell seals go, but what are they doing underwater? This unknown behavior is one of the things that makes this project so exciting. While we can see land animals move and migrate across the landscape, we usually have no idea what marine mammals are doing underneath the water. Below is one image showing all the dives from one animal throughout the year.

Comments