This journal brought to you by...

- Ms. Tony’s 6th grade students at St. Philomena’s School in Illinois

- Ms. Allen and Ms. McIllwain’s 3rd grade students at Germantown Elementary

- Ms. Blanchard’s ESL classes at Fox Meadows Elementary

- Ms. Alm’s 4th grade students at ECS

- Bradley Stubbs in 1st grade at Crosswind Elementary

Weddell Seal’s Fur & Molting

As mammals, Weddell seals have fur all over their bodies. And what fur they have! Look at this Weddell’s gorgeous coat! Weddell seals usually have silver-gray fur, often dotted with lighter spots. The fur is short, only about 1 inch long. It’s straight and much denser than the hair on our heads. When Weddell seals are first born, they have a fluffy, light gray coat with lots of warm, downy hairs.

Adult Weddell seal don’t have much down hair, because they don’t need it. They have a thick layer of blubber to keep them warm.

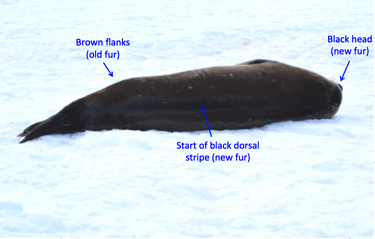

But Weddell fur doesn’t always look this sleek and shiny. Check out this seal’s coat – it’s brittle, brown and dry! Are some Weddell seals just prettier than others? No! So, what’s going on?

Molting is essential

Each year, Weddell seals molt or shed their fur. After an entire year of wearing the same coat of fur (in seawater, cold temperatures and wind), their fur gets brown and dry. So, in January and February, it is time to replace it with a nice, new silver coat. This isn’t unusual; all mammals have to replace their fur. You may not notice it, but even we fall into this category! Humans are constantly losing skin and hair. Unlike us, Weddell seals replace their fur at a certain time of year, instead of continually. That’s what makes the change so dramatic. Sometimes, we will find a seal that is halfway through the process!

Fur, ice and sun

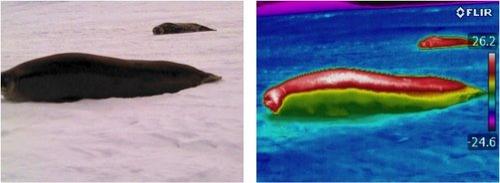

Weddell seals are often seen ‘hauled out’ on the ice every year between October and February. This is spring and summer in Antarctica, and the seals are taking advantage of the ‘warm’ sun. While it doesn’t feel all that warm to me, to a Weddell seal, it’s a little like sunbathing! But instead of a tan, they get a new fur coat! And the warmth of the sun actually helps the molting process. Their new hair grows faster if their skin is warm. That’s one reason why seals don’t spend as much time in the water this time of year.

Before we begin examining a seal, we take a thermal image of it. This is amazing! Thermal imaging is basically a photograph that shows the temperature differences of the seal's body. The warmer the area, the more likely the seal is to molt there. Check out this thermal image of one of the seals spotted last year. Notice the ‘red’ stripe down its dorsal side. The red color indicates that the seal was about to shed in that area.

An expensive new coat

Growing an entirely new fur coat is expensive! No, these seals aren’t spending money to get this new coat. They are spending energy! A seal’s fur is made of protein, like our hair, and making protein uses energy. Since seals need to keep their skin warm during the molt, they use energy to do that. Do you see a problem with that?

If the seal is using energy to keep its skin warm, more of the seals heat is lost to the environment. The seal then needs to burn more calories to maintain the same core body temperature. Seals also use up stored energy (body fat) just to keep their bodies running while they’re molting, since they can’t get in the water to look for food very much while they are keeping their skin warm.

These energy ‘costs’ add up to a lot!

Another energy-expensive task for these seals is giving birth and nursing their pups. Raising a pup is so expensive that over the course of the nursing period (about 6 weeks), the new mom loses about 30-40% of her body weight! Wow, that’s a lot!

It is not likely that a female seal will do these ‘expensive’ tasks at the same time. First comes nursing, then molting. This is smart! You don’t want to spend all of your energy at once! Most seals that have a pup don’t start molting until at least a month after weaning their pups. This way, they have a break after nursing, which they use to find lots of food and gain weight. The weight they gain can then be the fuel that powers them through molting.

Fur sample science

The molting process is one of our main focuses this year out on the ice. Weddell seals have a very specific time frame for their critical life history events, like pupping and molting. Our research team wants to better understand these ‘big events,’ and how environmental factors may affect these changes.

So, how do we do this?

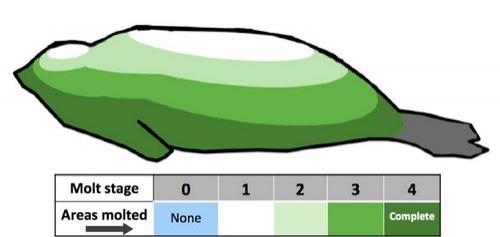

First, we observe which seals are molting and how far along in the molt they are. Weddell seals molt their fur in a pattern. First, they shed the fur on the tops of their heads and their backs. Next, they shed a bigger stripe on their backs. The stripe gets wider and wider until the seal has new, silver fur all over. Based on how much fur is molted, we can put the seal in a molt category. Then, we can see how many seals were in category 0,1,2,3 or 4 at different times, and if their molt category is related to whether they had a pup or how fat they are.

Every time we capture a seal, we also take a small fur sample and a skin sample. We study these samples in the lab. They can actually tell us a lot – what the seals have been eating, what stage of growth their fur is in, whether it is new fur or old fur, and lots of other stuff. To get the samples, we shave a little patch of hair.

This shaved patch serves another purpose. We’ll be trying to find these seals again in January. The first thing the research team will do is see if the hair in that shaved patch has grown back! In the past, we’ve seen that the seals that had not had a pup, the ‘skip breeders,’ had completely regrown their hair. The new moms, on the other hand, had little to no growth in the shaved patches.

Why aren’t the new moms re-growing their fur? It looks like the ‘skip breeders’ are molting earlier than breeding moms. Why is this happening? Our research team is trying to figure that out, but they do have a hypothesis!

Remember how expensive raising a pup is? The ‘skip breeders’ that did not recently have a pup didn’t have to spend all that energy, so they have more stored up. This means they have the fuel they need for the molt ready early in the summer. It is in their favor to molt sooner, so that they don’t have to molt at the end of summer when it starts to get really cold. At least that’s what the scientist hypothesize. The sooner they molt, the sooner they can get back in the water and start rebuilding their energy stores again, too!

How do they build energy stores?

They eat, eat, eat!

This is our hypothesis, and right now, we are learning whether fatter seals are growing fur before skinnier seals. With the samples and measurements we take, we can figure out if food and energy are, indeed, what control when a seal molts.

Who knew you could learn so much from a little sample of fur?

Comments