Unexpected Mission

If you are using the map tab at the top of the journal page, you may notice that we have made a slight turn to the west instead of continuing NE towards the Le Maire Strait (in southern Argentina). Last evening, we received a request from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to adjust our course in order to recover a disabled underwater glider. An image of one type of underwater glider is shown on the Woods Hole Oceanographic Instititution information page on gliders. The gliders are autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that are programmed to record information such as salinity, temperature, currents, chlorophyll levels, etc. The autonomous nature of these gliders allows them to collect large quantities of data over long periods of time. The glider in question has not been working properly for some time, therefore, a request was made to collect the glider from the Drake PassageStrait, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans between Tierra del Fuego and the South Shetland Islands. Located about 100 mi (160 km) north of the Antarctic Peninsula, it is 600 mi (1,000 km) wide. and return it to port for maintenance/data recovery. After about two hours of searching, we located the glider around 1000. Look at the picture below to see why it took some time to find.

Permission was required to bring the equipment aboard the vessel. The glider was located in a position within the Chilian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). These zones generally extend to approximately 200 nautical miles from land. EEZs were established under the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea (1994). Under these laws, EEZs were established to provide nations with the exclusive rights to these areas. This includes marine scientific research. Permission was granted around 1200 and the glider was on deck by 1230. We resumed our course soon after. Tomorrow, we should reach the Le Maire Strait and, in another day and a half (or so), reach the dock in Punta Arenas, Chile.

Packing Update

The packing process is in full swing on the RVIB Palmer. Equipment must be cleaned, inventoried and stowed for shipment. The science team must account for everything that was originally brought aboard the ship. If they brought it, it must either be part of the return shipment, part of the recorded chemical waste, part of the sample shipments, or part of the general waste. With four different lab groups occupying the same lab spaces for the past 5 weeks, materials are all over the place. The teams are working hard to ensure paperwork is correct and materials are secured for shipment before we reach port late Friday/early Saturday.

Zodiac Ops

My time aboard the RVIB Palmer has been full of learning opportunities and new experiences. I have documented most of these experiences as they happen (or just a few days after). There is one experience, however, that I decided to save for one of my last journals. This experience will forever be one of the most amazing experiences of my life. In late September, while sampling seawater in Duse Bay (in the Bransfield Strait), we had the opportunity to board the small boats (Zodiacs) in order to collect ice samples. I mentioned collecting ice samples in last Saturday's journal, but there were definitely some differences between the two operations.

In last Saturday's ice collection operation, the ice was collected specifically in locations with sea-ice algae. The collection in Duse Bay was done specifically to collect ice from a region near land. In a number of previous journals, I have mentioned the low levels of iron in the Southern Ocean. The main areas where higher iron levels are detected are in coastal regions. This is because of the sediment that enters the water from the land.

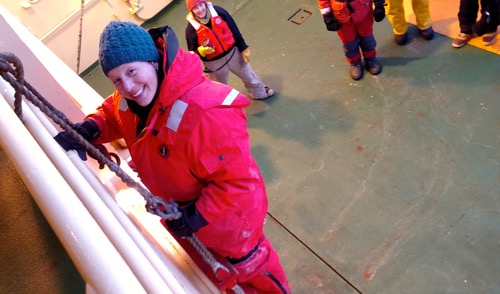

The second difference between the sampling in Duse Bay and the ice sampling from this past weekend is that I was directly a part of the process. Selfish...yes. Sorry...no. To collect the sediment-filled ice, the science team boarded small rigid inflatable boats or RIBs (often referred to as a Zodiacs because of the manufacturing company) to get as close to the ice along the shore as possible. The night before the small boat operations, science team members attended a training session on the main deck.

I was assigned to Small Boat #1 along with the ice collection science team and Marine Technicians Holly Martin and Jullie Jackson.

We left just after breakfast. The weather was great - light winds and calm seas. We sampled ice from the shores a few miles from the RVIB Palmer. We were right up against the fast ice (ice that is still attached to land). From a distance, this ice appears as a thin layer. Close up, the ice was at least 1-2 feet thick (sometimes more). Being close to the water provided a completely different perspective of the water, the ice and the surroundings. The collected ice was bagged and stowed for the ride back to the ship.

Consolation Prize(s)

During our sampling, the winds picked up and small waves filled the bay. This made for a wet, bumpy ride back to the RVIB Palmer. No one made it back to the ship without a good dousing (or two, or three, or many) of water from the waves. Our consolation? First, ice samples that will allow the trace metal team to analyze isotopic signatures from land. This type of sampling is very rare in this area. Understanding more about the isotope signatures can help scientists understand how the metals and other nutrients from land are influencing the waters in the area. The second consolation came in the form of our seal sightings. The Duse Bay area contained a large amount of fast ice - a perfect location for resting seals. Hundreds of crabeater seals were resting on the fast ice in the bay. While aboard the small boat, we had a eye-level view of these seals. At our closet point to the ice, Dr. Kristen Buck was busy sampling the ice and many of us were busy taking photos of the seals.

Comments