Finally, a week later, I present to you the materials from Dr. Alex Orsi's science talk. This might be the most technical entry of the journal, but it is also the most important as it presents preliminary results of the science being done aboard. It has more acronyms that I would like, so I ask you to be patient to the text and to read it a couple of times to fully understand the main idea from the cruise, which is spelled on the title.

Anne Marie, a PolarTREC teacher that finished her expedition two months ago along the very same waters we have been navigating, asked me a very hard question to answer. Before I get to her question, let me recommend you read her journal so you can make a simple comparison and observe the most obvious changes that two months brought to these waters. Her expedition was on a much bigger Swedish icebreaker, the Oden, since they were navigating through thick ice. The scientists aboard came out of the ship while on station to sample the ice, not the liquid water like we are doing.

Back to Anne Marie's question: 'It's been over 2 months since I finished my expedition on the Oden and I am grappling with the challenge of educating my students, parent, teachers, and the public about Antarctica and going beyond the 'penguins, seals, and icebergs' topics. What do you think is the most important information, or the 'Big Idea' that you will strive to share when you get home? What do you consider the 'key message' that you want people to learn about Antarctica and your research?'

I give thanks to Anne Marie for making me think about this very important question before I find myself facing that problem two months from now; after all, the whole reason for me being in this expedition is to do outreach for the science that is being done aboard, to 'educate my students, parent, teachers, and the public about Antarctica' as Anne Marie well wrote. There are many TV shows and magazines with professional photographers that provide you with much better images of penguin seals and icebergs than mine. So, what are the 'Big Idea' and the 'key message'?

On my vague response to Anne Marie I said the following 'the big idea I want to share about Antarctica is its fragility and the importance of scientific research to understand it. I wish I would know more about the results of our measurements and be able to speak more knowledgeably about the changes that the processes that provide sea water with its properties are going through.' The science talk of last week gave me a lifeline.

I am by no means an expert but Dr. Alejandro Orsi, a Professor of Oceanography at Texas A&M University, is. He helped me today by teaching us about some of the links between climate change and the Antarctic Ocean. Our Co-Chief Scientist gave a great talk entitled 'The Southern Pacific Ocean: an Alley of Global Change?'

The suggestive title of his talk comes from the evidence that the Southern Ocean is an active player in climate change. The basic premise of his talk, as I understand it, is: climate anomalies that arrive to the Southern Oceans from the north generate new anomalies by altering the multiple air-sea-ice interactions taking place over the vast Antarctic oceanic and continental shelf regimes. The new anomalies are then exported back to the north by Antarctic waters involved in the global Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC). This north-south exchange of anomalies constitutes the "Alley of Global Change" that Alex referred to in his talk.

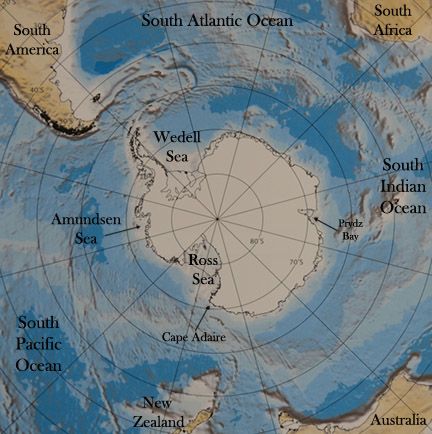

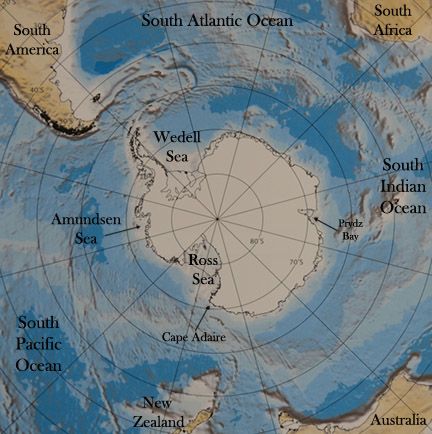

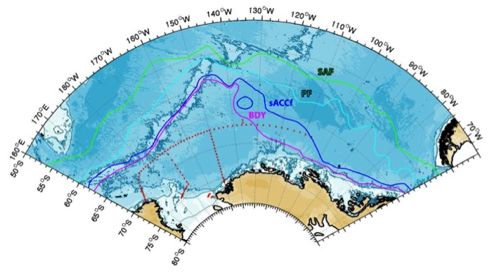

I will first present a basic description of Southern Ocean circulation and then explain what anomalies come from the north to disrupt this setting. Here is a map of Antarctica with some place names that I will refer to in the text.

Winds and currents

Some of the strongest prevailing winds in the world blow around Antarctica from west to east. These southern polar westerlies are particularly strong because there are no continental barriers to slow them down like other northern atmospheric jet streams are around the world.**

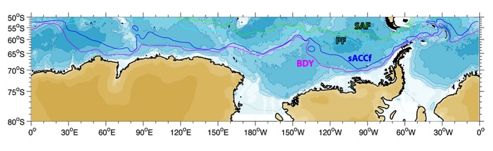

There is a similar ocean current around Antarctica that also flows uncontained by continents on its path. This is the Antarctic CircumpolarLocated or found within the Earth’s polar regions. Current (ACC) that flows from west to east. The current is actually made out of different jets. We can identify at least three of them within this current system.

Another strong current in the Southern Ocean is found farther to the south of the ACC and flowing in the opposite direction, that is toward the west and nearly along the continental shelf break. This is the Antarctic Slope Current (ASC), it is not as strong as the ACC and it does not continuously circumnavigate Antarctica: it collides with the ACC after turning around the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula from the Weddell Sea.

Water masses

We have seen in this journal that we can use the seawater properties along our cruise to identify three basic water masses. We have identified the Antarctic Surface Water (AASW) as fresh and cold water. This water mass shows a great deal of variability reflecting seasonal influences, like the summer warming and freshening caused by the melting of sea ice.

Over the largest Antarctic continental shelves near-freezing surface waters increase their salinity due to extensive brine release during sea ice formation and become much denser than AASW, the so called Shelf Water. At a few sites SW nears the shelf break from the south and sinks to great depths entraining less dense ambient waters, thus forming the familiar Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW). Northward outflows of AABW along Deep Western Boundary Currents fill most of the abyssal layer of the world ocean. A voluminous water mass of the Southern Ocean is found sandwiched between the AASW and AABW is the CircumpolarLocated or found within the Earth’s polar regions. Deep Water (CDW). I have previously mentioned that this water mass is the long term mixing product of AABW and deep waters entering the ACC from the north in each ocean basin, that is the North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW), Pacific Deep Water (PDW) and Indian Deep Water (IDW) [see schematic from Schmitt paper used in the blog before].

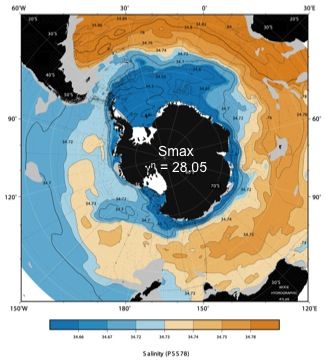

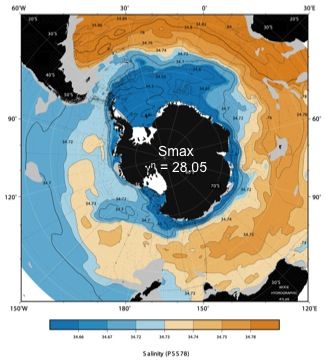

Let us focus on the fate of the NADW in the Southern Ocean, since it is the only source of salt for the CDW that reaches the Antarctic shelf break, where it is also warmer than the AASW above and AABW below. Saline CDW would first need to cross the ACC, and that is not an easy task because the current is very strong. The picture below is a map of the warm and salty signal of the NADW arriving to the Antarctic CircumpolarLocated or found within the Earth’s polar regions. Current in the southwestern Atlantic Ocean. The orange shades (tongue) indicate how the NADW becomes less salty as it travels towards the east around Antarctica progressively mixing with the fresher waters above (IDW and PDW) and below (AABW). The lower portion of this water (the Lower CDW) crosses the ACC and shoals towards Antarctica, e.g. some of it arrives to the shelves of the Amundsen, Ross and Weddell seas. This image is from the amazing WOCE Southern Ocean Atlas. I have used several of the images below. It is great as a classroom resource.

There are four mayor areas where Antarctic Bottom Water is produced: the Weddell Sea, on the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula, is thought to be the biggest formation site. It produces a very cold and relatively fresh type of AABW. The Ross Sea, where we began our cruise, is the second most important producer of AABW, and it has historically been known to produce cold and very salty type. The Adélie Sea and the Prydz Bay in the Indian Ocean sector also produce fresh AABW.

The extremely opposite scenario is seen over the continental shelves of the Amundsen Sea and West Antarctica Peninsula (WAP). Warm LCDW floods those margins either delaying or completely preventing the formation of sea ice in the winter. That is also the reason why the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula is one of the few parts of the entire coastline with no large ice shelves.

Changes in the Southern Ocean

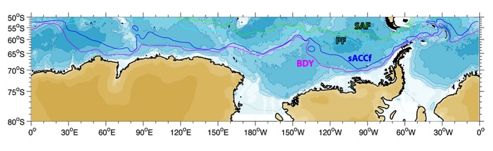

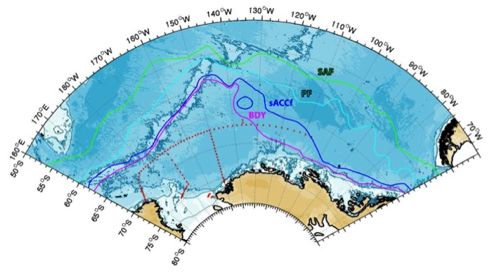

Alex Orsi was so generous with his time that he wrote what follows. Observational atmospheric studies have shown that the Antarctic westerlies have intensified and moved southward in past decades as a result of global warming. This is a climate anomaly arriving to the Southern Ocean from the north. Consequently the Antarctic CircumpolarLocated or found within the Earth’s polar regions. Current has also shifted polewards in response to that large-scale atmospheric change. It is well-known that prominent bathymetric ridges in the Southern Ocean effectively constrain the path of the ACC, for example the Southwestern Pacific Ridge limits the poleward extent of that current. But in the southeastern Pacific there are no such limiting topographic features, and the ACC is "free" to fluctuate in the north-south direction. This oceanic response to wind patterns can be inferred in the data collected during our cruise.

The southward motion of the ACC may increase the availability of relative warm deep water (LCDW) to the shelves further to the south, thus altering melt rates of glaciers at their floating base and grounding line. This has been recently observed in the Pine Island GlacierA mass of ice that persists for many years and notably deforms and flows under the influence of gravity. (PIG) at the southern edge of the Amundsen Sea, where we are headed today.

There is a series of troughs in this shelf that helps to channel the LCDW inflow to the south. Here the bottom water is warm and flows inshore, and it is able to reach and melt the base of the PIG. Basal melt produces a very cold but also anomalously fresh type of AASW that is less dense than LCDW. As this locally produced surface water moves away from the ice shelves and reaches the shelf break, the strong westward-flowing Antarctic Slope Current (ASC) described above carries the local fresh water anomaly downstream, towards the Ross Sea.

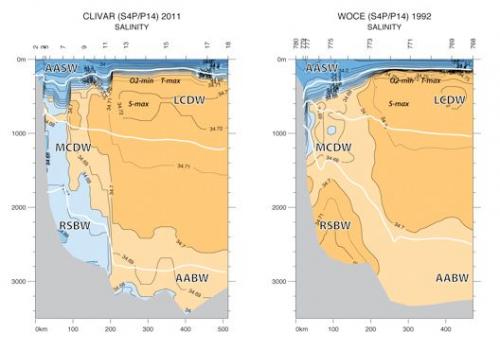

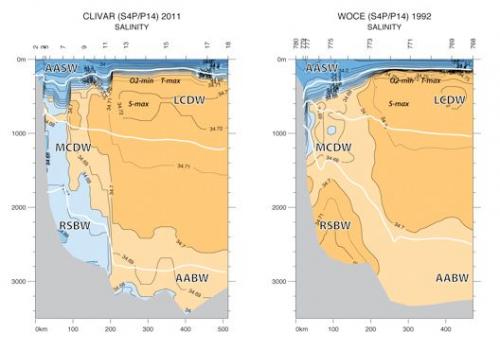

The arrival of any type of fresh water anomaly to the Ross Sea has important consequences, because that shelf is an important formation site of AABW. Even if the total amount of AABW formed in this area each year were unaffected by this anomaly, the characteristics of the end mixing-product will most likely reflect the change in one of its source water masses. In fact observations from this cruise show that one of the outflows of newly formed Ross Sea Bottom Water (RSBW) is much fresher than it used to be in previous decades. The figure below shows two cross-slope vertical sections of salinity occupied just downstream of Cape Adare; the one on the left is from 1992 (WOCE S4P) and the other one from the beginning of this CLIVAR repeat cruise. The vertical axis has the depth in meters and the horizontal axis is the distance traveled by the ship in kilometers. Note the overall salty ("orange") deep and bottom layers in the older section, compared to the much fresher ("bluish") picture at present time.

It is clear that new bottom waters sinking near the shelf break of the western Ross Sea are fresher than they were almost 20 years ago. This change in water properties will have a significant impact on the rest of the abyssal ocean, since AABW outflows to the north are the primary suppliers to the lower limb of the global Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) mentioned before. As this Antarctic anomaly propagates to the north it completes the exchange along the "Alley of Global Change".

The Ross Sea could experience a shift in modes of circulation in the future, at least in terms of cross-slope exchange with the deep ocean. Hypothetically the Ross Sea could become the next Amundsen Sea, if at some point LCDW is to become more available to the base of the Ross Ice Shelf (RIS) and begins to melt it. In February 2010 our team from Texas A&M University sailed on the Oden icebreaker to deployed two moorings along the first likely entry point of LCDW to the eastern Ross Sea shelf, just west of Cape Colbeck. From the analysis of the multiple 1-yr time series of ocean currents and seawater temperatures and salinities that were recovered on this cruise (see journal March 20), we might find evidence of warm water pulses toward the RIS and ensuing "super-cooled" outflows. Let us hope that this is not the case, and that the world's largest ice shelf remains stable for a few more centuries.

The big idea

This is the big idea I want to communicate to my students, their parents and the general pubic about Antarctica. Antarctica is remote but fragile. We need to understand the processes that create and shape this unique environment, and how these processes respond to global changes originated very far away. We only have one Antarctica. It is through the work of dedicated scientist like Alex and others aboard the ship, that we will be better prepared to face future challenges in this corner of the world. Specifically, we have found that the properties of deep seawater formed in the Ross Sea are changing due to the displacement to the south of the ACC that is a consequence of the displacement of the South Polar Westerlies also to the south in response to climate change. The change in properties of deep waters, freshening in this case, will very likely have an impact on the world's abyss.

Alex's talk covered a lot more material that what is presented here, which I unsuccessfully tried to soak up like a sponge. I plan to keep on asking him questions around this topic during the upcoming couple of weeks; you should do the same. Take the opportunity to talk to an expert oceanographer, send me your questions and I would ask Alex about the extremely important work he is doing.

I would like to thank Alex for his unlimited patience that allowed me to understand what I present here.

Mensaje clave: Cambios en las propiedades del agua marina ligadas al cambio climático

Finalmente , una semana más tarde, te presento el material de la charla del Dr. Alejandro Orsi. Este diario pudiera ser el más técnicos de los que he escrito, pero también es el más importante ya que presetna resultados preliminares del crucero. Tiene más acrónimos de los que yo quisiera, así que te pido que le tengas paciencia al tecto y que lo leas al menos un par de veces para que puedas entender la idea más importante del crucero, que esta escrito en el título del diario de hoy.

Anne Marie, otra maestra PolarTREC que terminó su expedición en estas mismas aguas hace dos meses, me mandó una pregunta al foro difícil de contestar. Antes de ver su pregunta, te recomiendo que leas su diario de expedición para que puedas observar los cambios que dos meses han traído a estas aguas. Su expedición fue en un rompehielos mucho más grande, el Oden de Suecia, ya que navegaron por hielo más grueso. Los científicos de abordo salieron en las estaciones a muestrear el hielo en vez de muestrear el agua líquida como hacemos nosotros. Suena muy interesante, ¿no crees?

Regresemos a la pregunta de Anne Marie:

'Hace más de dos meses que terminé mi expedición en el Oden y sigo enfrentando el reto de educar a mis estudiantes, papás de los estudiantes, maestros, y el público en general sobre Antártica más allá de 'pingüinos, focas y témpanos de hielo'. ¿Cuál consideras es la información más importante que quieres transmitir, o la 'Gran Idea' que intentarás comunicar a la gente cuando regreses? ¿Cuál piensas que será 'el mensaje clave' que quieres que la gente aprenda sobre Antarctica y tu investigación?'

Le agradezco a Anne Marie por hacerme esta pregunta tan importante antes de que termine mi expedición y me encuentre frente al mismo reto dos meses de aquí en adelante; después de todo, la razón principal para que yo pueda participar en esta expedición es el divulgar la ciencia que se hace abordo, para 'educar a mis estudiantes, papás de los estudiantes, maestros, y el público en general sobre Antártica' como bien dijo Anne Marie. Existe un número infinito de programas de televisión y revistas con fotógrafos profesionales que tienen muchas mejores imágenes de pingüinos, focas y témpanos de hielo de las que yo puedo presentarte. Así que, ¿cuál es la gran idea o mensaje clave?

En mi respuesta vaga a Anne Marie escribí: 'La idea principal que quiero transmitir es la fragilidad de Antártica y la importancia que tiene el trabajo científico para entenderla. Quisiera saber más sobre los resultados de nuestras mediciones para poder hablar sobre los cambios que han sufrido los procesos que determinan las propiedades del agua de mar en esta región', Y bien, la charla científica de hace una semana me tiró un cable.

Yo no soy un experto en el tema, pero el Dr. Alejandro Orsi, profesor de oceanología en la Universidad Texas A&M, si lo es. El me ayudó al enseñarnos sobre las nexos que existen entre el cambio climático y los Mares del Sur en una charla titulada 'El Oceano Pacifico del Sur: ¿un callejón para el calentamiento global?'

El título sugestivo viene de la evidencia que muestra a los Mares del Sur como actores activos en el cambio climático. La premisa básica de la charla, como yo la entendí, es: anomalías climáticas llegan al océano Antártico desde el norte y generan nuevas anomalías en estos océanos al modificar las múltiples interacciones entre el aire-mar-hielo que ocurren en el océano y sobre las plataformas continentales. Las nuevas anomalías son exportadas hacia el norte por las aguas de la Antártida que están involucradas en lo que se conoce como Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC). Este intercambio de anomalías entre el norte y el sur constituyen el callejón del cambio climático al que se refirió Alex en su plática.

Primero te presentaré el escenario básico que gobierna las aguas de la Antártida y después explicaré las anomalías climáticas. Aquí un mapa de la Antártida con los nombres de los lugares a los que haré referencia en el texto.

Vientos y Corrientes

Algunos de los vientos predominantes más fuertes del mundo soplan alrededor de la Antártica del oeste al este. Estos vientos son particularmente fuertes porque, a diferencia de otros vientos fuertes, éstos no se topan con barreras topográficas que los frene.

Existe una corriente oceánica similar que se mueve alrededor de la Antártida que tampoco se topa con algún continente en su camino. Esta es la Corriente Circumpolar Antártica (ACC, por sus siglas en inglés), que también circula de oeste al este. La corriente es en realidad un conjunto de fuertes chorros. Podemos distinguir al menos tres principales chorros en esta corriente. De hecho, Alex fue el primero en identificar el chorro más sureño.

Otra corriente fuerte en los Mares del Sur está más pegada a la costa, sobre la pendiente de la plataforma continental, y circula en dirección opuesta al ACC. Esta corriente no es tan fuerte y no logra circumnavegar a la Antártida; choca con la ACC después de librar la punta de la península Antártica en el Mar de Wedell.

Masas de agua

Hemos visto con anterioridad en este diario que podemos usar las propiedades del agua de mar para identificar tres masas de agua en estas regiones. Hemos hablado del agua muy fría y dulce del Agua Superficial de la Antártida (AASW). Esta agua muestra gran variación en respuesta a las estaciones; por ejemplo, el agua se calienta y se vuelve menos salada en verano por el deshielo en superficie.

Sobre las plataformas continentales más largas de la Antártida las aguas que están muy cerca del punto de congelación se vuelven más densas que el AASW por la salmuera que libera el agua que se congela. En algunos sitios, esta agua se mueve hacia el norte hasta el borde de la plataforma continental donde se hunde a grandes profundidades y se mezcla un poco con aguas ambientales menos densas hasta formar la ya conocida Agua de Fondo de la Antártida (AABW). Esta agua fluye hacia el norte a lo largo de corrientes de grandes profundidades que ocurren en la parte oeste de la cuenca (Deep Western Boundary Currents) y se desparrama por el fondo de todos lod océanos. Una masa de agua de gran volumen se encuentra a profundidad media entre las otras dos. Esta es el Agua Profunda Circumpolar (CDW). Antes dije que esta masa de agua es producto de la mezcla de las Aguas Profundas del Atlántico Norte (NADW) con otras aguas sin dar mayor detalle. En realidad también contribuyen en su formación aguas del Pacifico Norte (PDW) e Índico Norte (IDW). Todas estas masas de agua se mezclan en la corriente circumpolar (ACC).

Enfoquémonos ahora en la transformación del NADW en los Mares del Sur, ya que es la única fuente de sal para el CDW que llega a la plataforma continental de la Antártida, donde también es más cálida que la AASW que le queda arriba y la AABW que le queda debajo. El agua salada de la NADW tiene que cruzar la Corriente Circumpolar Antártica (ACC) antes de llegar a la plataforma continental, cosa nada fácil ya que la ACC es muy fuerte. El mapa inferior muestra la señal salada de la NADW al llegar a la ACC en el suroeste del Océano Atlántico. Los contornos naranja muestran como la NADW se vuelve menos salada al viajar hacia el este alrededor de la Antártida conforme se mezcla con las aguas más dulces de superficie (IDW y PDW) y del fondo (AABW). La parte inferior de esta masa de agua (LCDW) cruza la ACC y se vuelve menos profunda hacia Antártica, i.e. parte de LCDW llega a las plataformas continentales en los mares Amundsen, Ross y Wedell.

Hay cuatro áreas en las que se produce el Agua Profunda de la Antártida (AABW): el mar de Wedell, al lado est de la península Antártica, se considera el área de mayor producción. Esta zona produce un tipo de agua del AABW muy fría y relativamente dulce (poco salada); el mar de Ross, donde iniciamos el crucero, es la segunda área de mayor producción de AABW, e históricamente ha producido agua del tipo fría y salada. El mar de Adélie y la bahía de Prydz en el sector del Océano Índico también producen AABW del tipo frío y dulce.

La situación completamente opuesta se observa en las plataformas continentales del Mar de Amundsen y la parte Oeste de la Península Antarctica (WAP, por sus siglas en inglés). El agua cálida de la LCDW alcanza esas márgenes lo que retrasa o previene completamente la formación de hielo durante el invierno. Esta es la razón por la que el lado oeste de la península es una de las pocas partes de la costa Antártica que not iene grandes plataformas de hielo.

Cambios en los Mares del Sur

Alex Orsi ha sido muy generoso con su tiempo y ha escrito esta sección. Los errores de traducción son míos. Estudios observacionales de la atmósfera han mostrado que los vientos del oeste alrededor de la Antártida se han intensificado y desplazado hacia el sur en las últimas décadas como respuesta al calentamiento global. Esta es una anomalía que llega a los Mares del Sur desde el norte. Como consecuencia, la Corriente Circumpolar Antártica también se ha desplazado hacia el polo en respuesta a ese cambio atmosférico de gran escala Es bien conocido que las cordilleras batimétricas en los Mares del Sur restringen la trayectoria de la ACC. La cordillera en el suroeste del Pacífico restringe el desplazamiento al sur de la corriente, pero en el sureste del Pacífico no hay cordillera que limite el desplazamiento, por lo que la ACC puede fluctuar libremente de norte a sur. Esta respuesta oceánica se puede inferir en los datos colectados durante este crucero, como se indica en la imagen inferior.

El movimiento al hacia el sur de la ACC puede aumentar la disponibilidad de agua relativamente caliente (LCDW) en las plataformas continentales más al sur, lo que alteraría la velocidad de deshielo de los glaciares en su base de flotación o donde tocan tierra. Esto se ha observado recientemente en el glaciar de Pine Island en el borde del sur del Mar de Amundsen, hacia donde nos dirigíamos hace unos días cuando la nueve en el hielo nos detuvo la marcha.

La plataforma continental frente a Pine Island presenta una serie de cañadas que canalizan la LCDW hacia la costa, por lo que el agua de fondo en la plataforma continental es cálida. El agua cálida llega hasta la costa donde alcanza y derrite la base del glaciar de Pine Island. Este derretimiento basal produce agua muy fría, pero anómalamente dulce para la AASW, que es menos densa que LCDW. Esta agua superficial de producción local se desplaza hacia el norte, lejos de la costa, y llega al borde de la pendiente continental, donde la corriente fuerte que fluye hacia el oeste, la Antarctic Slope Current (ASC) que se describió con anterioridad, la transporta hacia el Mar de Ross.

El arribo de cualquier anomalía de agua dulce al Mar de Ross tiene consecuencias importantes ya que esa plataforma continental es muy importante en la producción de agua de fondo (AABW). Aún cuando esta anomalía no haya cambiado el volumen total del agua que se ha formado en esta región durante los últimos años, las características de esta agua probablemente reflejan los cambios en la zona de producción. De hecho, las observaciones de este crucero muestran que una de las salidas de la recientemente formada Agua Profunda del Mar de Ross (Ross Sea Bottom Water, RSBW) es mucho más dulce de lo que era décadas atrás. La imagen inferior muestra la misma sección de salinidad obtenida en la parte oeste del Mar de Ross en diferentes años. La de la izquierda refleja las condiciones observadas en 1992 (crucero WOCE S4P) y la de la derecha obtenida al inicio de este crucero (CLIVAR S4P). El eje vertical tiene la profundidad en metros y el horizontal la distancia recorrida por el buque en kilómetros. Nota que por lo general las aguas profundas de 1992 son más saladas (naranja) que las actuales, que se muestran más dulces (azules).

Esto muestra que el agua que actualmente se está hundiendo cerca del borde de la pendiente continental oeste del Mar de Ross es más dulce que lo que era hace 20 años. Este cambio en las propiedades del agua tendrá un impacto significativo en el resto del los abismos mundiales, ya que el AABW fluye hacia el norte y es el principal proveedor de agua a la parte inferior de la circulación Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) que se menciono antes. Conforme esta anomalía se propague hacia el norte completará el intercambio en el 'callejón del cambio global'.

El Mar de Ross podría sufrir un cambio en los modos de circulación en el futuro, al menos en lo que se refiere al flujo de agua con el mar profundo a través de la plataforma continental. Hipotéticamente el Mar deRoss se puede convertir en el siguiente Mar de Amundsen si en algún punto LCDW llega a la base de la Plataforma de Hielo de Ross y la derrite. En febrero del 2010 el equipo de Alex de la Universidad de Texas A&M navegó en el rompehielos Oden para colocar dos fondeos en las primeras dos cañadas que permitirían el flujo de LCDW a la plataforma de hielo, al oeste del Cabo Colbeck. Estos son los dos fondeos que recuperamos en este crucero (diario del 20 de marzo). Los análisis preliminares de las series de tiempo de un año que de temperatura y salinidad que se obtuvieron en dichos fondeos, presentan evidencias de pulsos de agua cálida hacia la Plataforma de Hielo de Ross y flujos hacia afuera del Mar de Ross de agua 'super-fría'. Esperemos que este no sea el caso, y que la plataforma de hielo más grande se mantenga estable por muchos siglos.

La gran idea

Esta es la gran idea que quiero comunicarle a la gente para educar a mis alumnos, sus padres y el público en general: La Antártida es una región remota pero frágil. Necesitamos entender los procesos que han creado y dan forma a este ambiente único. Necesitamos entender la respuesta de estos procesos a los cambios que se originan muy lejos. Tenemos una sola Antártida. Será a través del trabajo de los científicos como Alex y los demás que se encuentran hoy en el Palmer, que podremos estar mejor preparados para afrontar los retos que se verán en este rincón del mundo en el futuro. Específicamente, hemos encontrado que las propiedades del agua profunda que se forma en el Mar de Ross han cambiado debido al desplazamiento hacia el sur de la ACC, que es consecuencia del desplazamiento también al sur de los vientos del oeste, como respuesta al cambio climático. El cambio en las propiedades de las aguas profundas en el Mar de Ross, pérdida de salinidad en este caso, tendrá, probablemente, un fuerte impacto en los abismos mundiales.

La charla de Alex cubrió más material del que aquí presentamos Alex y yo. Intenté infructuosamente absorber como esponja todo lo presentado por Alex, y planeo seguir preguntándole sobre el tema en los pocos días que nos quedan abordo. Te invito a que hagas lo mismo. Aprovecha la oportunidad de hablar con un oceanólogo experto y mándame tus preguntas par que se las haga llegar a Alex.

Le agradezco a Alex si infinita paciencia que me ha permitido entender mejor lo que aquí presento.

Comments