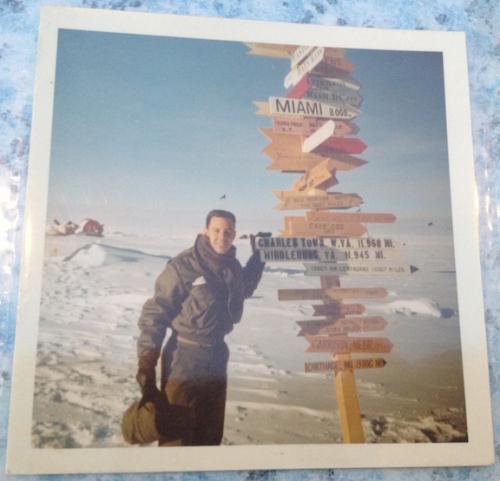

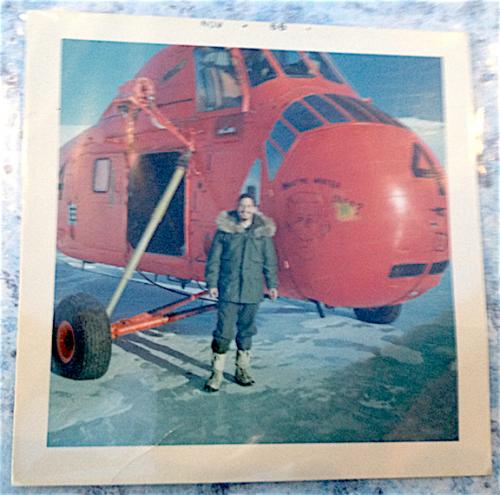

In the austral spring of 1966, Ned Goldsmith was a young US Navy lieutenant assigned to McMurdo Station to fly helicopters. Over the course of a few deployments in the late '60s, Goldsmith was a witness to, and sometimes a participant in, some pioneering exploits of Antarctic aviation. A decade after the International Geophysical Year and the establishment of McMurdo Station, Ned and the scientists he carried aboard his Sikorsky H-34 were still among the first to stand on certain parts of Antarctica, visiting places literally no one had ever been. Now in his seventies, Ned - a neighbor and friend of mine in Washington State - found out that I was headed to Antarctica 50 years after his first deployment, and he and his son, Chris, invited me to dinner to share some photos and stories.

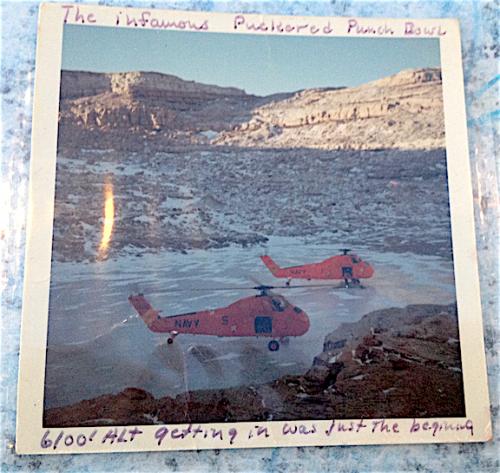

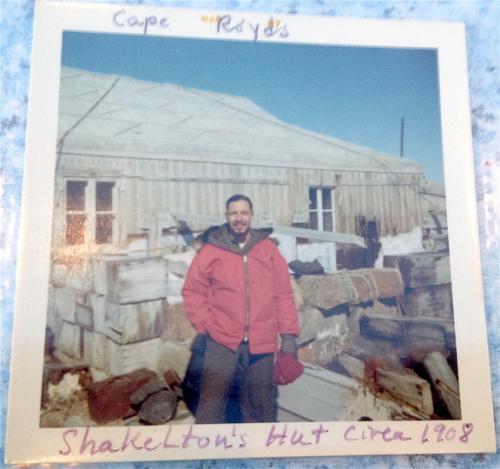

"I wasn't fond of helicopters," Ned confided while I flipped through his photo album. "I thought you said you hated them," Chris, a pilot himself, rebutted. Chuckling, Ned replied, "Well, that's true. And the H-34 was always finding new ways to tear itself apart. Before each flight I used to open up every door and hatch and stick my head in. I didn't know what I was looking for but I could tell when it wasn't right." Amid stories of waterspouts, whiteouts, and flying backwards in severe winds, Ned mentioned that one of his greatest achievements was landing a geology crew in the crater of an extinct volcano at 6100ft/1860m. "Of course, the rim of the thing was at 7100ft (2165m) and getting back out was pretty wild," he offers. Over the course of a two hour meal, our conversation ranges from helicopter flight training, to chaperoning visits of the historic explorer's huts, to the distinguished visitors that flew with Ned, to the food on Station. One common theme runs the length of our discussion: Ned is grinning widely and laughing frequently, remembering his time in Antarctica with fondness.

The Sikorsky H-34s have long since been retired and Navy helicopter support for Antarctic operations ended in 1996, replaced by Petroleum Helicopters, Inc, a private contractor. But Ned Goldsmith and other resourceful pilots and aircrews that followed him have been making remote science possible in Antarctica for 60 years. Tomorrow, weather permitting, I'm excited to fly with the pilots of Helo Ops in their red helicopters out to Granite Harbor for some end-of-season field work with the team. I'm even more excited to have a helicopter story to tell Ned when I return home next month. And to let him know that food science still hasn't perfected powdered milk.

Comments