February 29, 2008

*Clouds refelected off the Ross Sea *

** How do you begin to describe an experience that has taken you farther than you thought you were capable of going? The Oden Southern Ocean Expedition carried us 5000 miles from Punta Arenas, SA to McMurdo Station Antarctica. We left family, friends, and basically all human contact behind as we sailed off at the end of November. All of the madness and rush to get everything in order for this lengthy journey stayed on the shores as I watched the continent of South America disappear. We had left the dock around 5am while I slept on Nov 30, but I awakened as we travelled through the Straits of Magellan. It seemed like it took a very long time before we reached the open sea. I had no idea then about the distance we would cover in the time that we had! But the geographical distance paled in comparison to the personal limits I ever thought I was capable of reaching.

There were many "firsts” on this journey: First time out of the continental US and traveling alone; first time away from home for an expedition of this duration; first time on a ship; first time doing an oceanographic study; first time working with such a large group of scientists at the same time; and certainly the first time in Antarctica! As I saw the last specks of land fall into the horizon behind us, I looked forward to the sea that had opened up and stretched as far as I could see. I remember thinking "I am really doing this!” I prayed that I would be a real contributor to this expedition, and I wondered what lay ahead. Before long, we were alone on an endless sea that beckoned with inviting mystery!

As we began our transit across the Drake PassageStrait, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans between Tierra del Fuego and the South Shetland Islands. Located about 100 mi (160 km) north of the Antarctic Peninsula, it is 600 mi (1,000 km) wide., I thought of my classes back home and the studies we did on Ernest Shackleton’s journey. I remembered the courage we discussed about those mariners as we read of their crossing in vessels much smaller than the six story ice breaker we were traveling in. With the most meager of equipment and supplies, that group of sailors overcame insurmountable odds to survive their historical journey. Standing on the bow of the Oden with the wind pushing against me I could feel the power and the magic of the seas that has driven it’s exploration for hundreds of years. The human spirit is driven by challenge- and I was ready to take on whatever the seas would give us!

The actual transit across the Drake PassageStrait, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans between Tierra del Fuego and the South Shetland Islands. Located about 100 mi (160 km) north of the Antarctic Peninsula, it is 600 mi (1,000 km) wide. took longer than I had expected (about a week). But, it was much calmer than I anticipated, a view shared by many on the ship. I figured the worst was over- on to the ice! I settled in to a routine of work, journaling, meetings, emails home, and precise mealtimes. I also established a mandatory exercise time in the gym, and whatever time was left over, I dedicated to documenting the expedition through photography and video.

By this time, I had volunteered to help anyone who needed another hand in their science work. The first science project was the whale bone experiment conducted by PI Kirsty Kemp in collaboration with Thomas Dahlgren. In the pre-dawn hours of Dec 3, Kirsty gave me a promised wake-up call and I found her on the aft deck. I don’t think she thought I was serious about getting up to see her preparations until I showed up! Although I couldn’t help with the work at hand (attaching the whale bones to the landers), I did take pictures to record the process while I interviewed her about her work. Kirsty was patient with my questions and excited about her work. It was during this early morning interview that I realized how many wonderful new things I was going to learn. And I wondered how effective I could be in getting this back to everyone following the journey.

Sometime after we passed the Shetland Islands where the whalebone project was done, we encountered the first of several storms at sea. It was a sight hard to record except in the memories of the mind. The listing of the ship brought to mind tow bits of advice I always remembered. The first, from my husband: "stay focused!” the other from the ship’s doctor Krister "Always keep one hand on the ship”. He meant 24 hours a day and I always remembered! For all the rolling we did, I was glad to be able to stand and watch the storm instead of succumbing to its power. This was the challenge I was most anxious about- and I got through it!

Soon after we were underway, PIs Rob Sherrell and Tish Yager recruited me for work in the CTDA research tool that is submerged in the water to measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth. shack documenting data. I also helped on deck with the Kevlar lines for the TMCTD (they needed height to hold them up!) It was great being a useful part of this type of sampling. I had never seen a CTDA research tool that is submerged in the water to measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth. or a CTDA research tool that is submerged in the water to measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth. cast before this expedition, and I learned so much about water sampling from working with Rob, Tish and the crew. I learned about all the parameters that a CTDA research tool that is submerged in the water to measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth. documents, as well as how clean samples are taken, how many investigations depend on them, and how I could use this information in my classrooms. As a proponent of teamwork, the idea of being part of this team documenting real science gave me a sense of value to the expedition besides being "the teacher” onboard. And everyone who worked the casts took time to explain all the different parts of this kind of sampling.

As I talked more with the other scientists, I realized how many different types of projects were underway. I wondered how I could cover all aspects of the science, and be a contributing member. I began with interviewing everyone about their work. We spent many evenings discussing the science as they explained the whys, how’s, and where’s. At all times, every one of them (US and Swedish team members) showed sincere enthusiasm in making sure that I understood so that I could get the message about their science back to the classrooms and everyone who was interested.

Another assignment came in an invitation from the Swedish expedition leader and scientists to join them on the ice for ice coring! I was ecstatic to be able to do this! (I had expressed my interest in this many times over!!) As I was ferried over the aft deck onto the ice, I registered another "first "in my mind, and I wished my family could have seen thisJ Once I landed, it was all business. I recorded the data as requested while I made pictorial records of the ice coring process. PIs Agneta Fransson and Melissa Chierici did a great job of discussing the process as they worked. This marked the beginning of a new friendship and a continued collaboration during the rest of the journey.

PI Rebecca Dickhut also stands out as a special mentor to me- literally and figuratively. She stands at over 6ft tall, while I stretch to make 4’11! That aside, she took me under her wing and taught me so much about the process of ocean studies. Rebecca was doing a collaborative project with Swedish PI Henrik Kylin. Their studies focused on POPS- Persistent Organic PollutantsSubstances that have a harmful effect on human and/or ecosystem health when present in high enough concentrations in water, air, or soil. Rebecca explained the details of their investigation and how the ice core, plankton net and air samples contributed to their studies. She also got me involved with the plankton net tows .The excitement in finding the first Pteropod on the cruise demonstrated the emotion generated by people who enjoy what they do. Rebecca, Melissa, and Agneta taught me a lot about the bioindicators that tell us about the health of the oceans, and introduced me to Phaeocystis J

At about the same time, PI Sharon Stammerjohn recruited me to organize some ice observations. Using guidelines from the SCAR ASPeCt program, I learned how to document visual observations of the ice field from the bridge of the ship. What a fantastic way to learn about sea ice! Basically, we were ground -truthing what satellites were showing us on radar. Jakob Wegelius , Kirsty, Rebecca, and Eleni Anagnostou also contributed to making observations. I have used this experience to develop a classroom activity about the different types of ice using my own photographs. Sharon also taught me about the XBT’s and their role in ocean studies. But I really enjoyed the informal chats we often had in the conference room at all hours of the day as we did our computer work. She was an incredible resource when it came to answering questions about the ocean. And I quickly learned why the other scientists held her in high regard!

While I didn’t play an active role in the other science projects, I developed an on-going dialogue and frequent lab visits to keep up with the other work being done. As I talked with each of the scientists and support staff, whether in the labs or over mealtimes, they always generously shared stories about their work, ideas, and the science. So thank you! –PI Henrik Kylin, PI Dave Hutchins, PI Janos Hajdu, PI Mark Dennett, PI Walker Smith, cruise PI Erik Mattsson, Daniel Barrdahl, Kevin Bakker, cruise PI Friederike Heinrich, Hannah Farnelid, Marvin Seibert, Eleni Anagnostou, Michelle Le Vigne, Glaucia Fragoso and Raytheon crew, Nicole Middaugh, Lindsey Ekern, and Kevin Pedigo.

As a teacher, I must applaud the graduate students who spent long hours in the labs and on deck. I have never seen a more focused group of young people with such strong work ethics and dedication. They were all an inspiration to me and reminded me of why I teach! These young people are the ones we will be looking to for answers someday and will be the ones who carry on the work started on this expedition. They validate the hope we have for the future, and I am very proud to have worked with them!

I have learned a lot about the relationship between the atmosphere, the ocean and the ice and snow. It has strengthened my confidence in teaching about it and my content knowledge about Polar science. I have also made good friends who I hope will continue a dialogue and collaboration with me. I have already expressed my gratitude to the ship’s crew in the previous journal for their part in making this a safe learning experience for me. They taught me a lot about life on a ship. And I have also already commended the staff from the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat for their incredible hospitality and cultural exchange (Cecilia, you helped me so much to understand the Swedish culture and language!). As it turns out, the science was not all this was about for me.

There was more! - A feeling of personal accomplishment traveling in the extremes of the Antarctic seas and a change in my thinking regarding the fragile balance of life on Earth. I will always remember the joy of standing on the ships foredeck with the wind daring me to stay as long as I could. Sometimes it felt like the skin on my cheeks was going to peel off with the force of the wind or the bitter cold. It was a favorite place of mine that afforded up- close views of the ice and sea as we moved in it.

I call this Castle berg!

*Approaching the continent of Antarctica- TransAntarctic Mountains *

**

The reminder of danger was always evident. One day as I opened a lab door to film Dave’s experiment, the powerful winds blowing that day grabbed the door and me with it. I let go as fast as I could with visions of Dorothy’s house in the wizard of Oz as the tornado took it up! I realized then the power of the forces around us, and that they needed to be respected.

The storms were another adventure. I remember Allan Miller (Oden 06), describing the ships rocking and rolling during high seas, and thinking I could never do that. But I did! There are many stories about the challenges of carrying on life’s duties during these episodes: showering, eating, sleeping, and trying to work on a computer J We were not allowed on deck during these storms, but watching the wave action from the bottom floor, or rolling with it from the top decks was an experience I can still feel. In fact, it took a while to lose the "roll” even after reaching terra firma!

*Storms approaching could be seen for miles. *

*That's the only time the horizon darkens! *

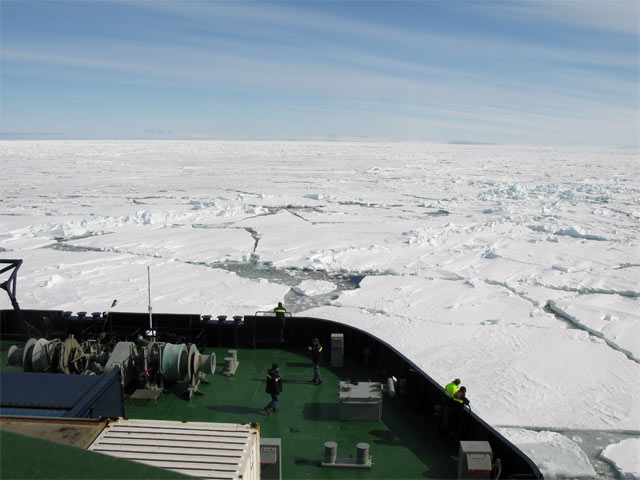

But if the storms were the "roll”, breaking ice was definitely the "rocking” part. I remember waking suddenly the morning of the 4th of January and thinking we must be having an earthquake! I felt and watched myself moving back and forth, side to side and up and down all at once!! "CCCECCiLLLia!!”- I called to my roommate, "what is going on????” We laughed as she spoke in broken, vibrating words:”I think we’re breaking ice now!” Serious ice! The remainder of our time on the ship was spent in this continuous jarring motion, but it was fascinating to watch the mighty Oden doing its real job. Huge slabs of ice broke and pushed and flipped over as we moved back and forth over it. The sounds of the crunching and breaking of ice were amazing and resonated throughout the ship.

*Oden begins breaking ice in McMurdo Sound *

Ice buckles as the floe is pushed.

Crunching and crashing of ice

And then there was watching the scientists carrying on in extremes of weather and conditions. I saw frozen lines, malfunctions in equipment, battering winds, blistering cold, and long, long hours of work. Their faces during these times captured that feeling of determination and dedication that drives the scientific quest. They are all a remarkable group of people.

But do not think that any of these experiences were bad things, "al contraire”. These were the forces and images that drove my own spirit of adventure, because I was not just an observer, but a participant in all I have described!

The beautiful images I have captured of the ice, the sea, and the science have more meaning because of the extreme environment I have experienced them in firsthand. I have repeated many times over the enchanting feeling of passing a single penguin standing on an ice floe as the ship sailed passed it. Every time, the penguin would turn and look at the ship as in wonder. I cannot imagine what they were thinking; but I realized what a unique and special place this was and why it was so important to protect "The Ice”- Antarctica. Winter will begin there soon and with it, a very long night. I wonder what the seas are like in the cold darkness of that season.

*A lone penguin watches the Oden pass. *

**

My sincere thanks to PolarTREC and the National Science Foundation for the honor of participating in this outstanding program.

Lollie Garay

Some final expedition facts to share about what we accomplished and did:

13 different science projects (combined US and Swedish) 34 stations with 76 CTDA research tool that is submerged in the water to measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth. casts 146 XBT/XCTD drops 148 salinity samples analyzed 82 oxygen samples processed and analyzed A three week incubation experiment examining the interaction between CO₂ and FE availability on phytoplankton community and biogeochemistry

50 air samples collected (aerosol and gas) from Gothenburg to the Ross Sea 13 ice stations 17 plankton net tows 132 biological samples collected looking for the smallest living fluorescent particles 5000 nautical miles traveled between Punta Arenas , Chile to McMurdo Station , Antarctica 36 journals posted on PolarTREC website 7 Languages spoken onboard the Oden 61 Towns /cities across the globe who followed the journey (that we know of). Lowest temperature was -11.1˚ (Jan 3) and highest was +3.1˚(Dec 17) Strongest wind – 35m/second (Dec 17) We ate – 1680 eggs, 500kg of potatoes, 200 gal milk, 30kg of lingonberry jam and more! J

*Lollie and Mt. Erebus *

**

Comments