Dec 20 A little lesson on Antarctic ice

Two of our researchers, Hongjie Xie and Burcu Cicek from University of Texas, San Antonio, have been patiently awaiting the arrival of ice. They are part of a longterm study of global ice conditions that can be seen at the website www.aspect.org if you are interested.

Who would have guessed that it would take a full week and over 1,000 miles before they could move beyond studying the cubes in their water glasses. But as you can see in this picture – by 10 AM today the sea had calmed and was full of remnants of this year’s sea ice breaking up and floating in the current and wind to the north.

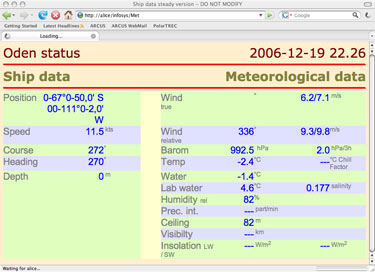

Our current location and weather information is

Latitude: 67 degrees 50 minutes south

Longitude: 111 degrees 2 minutes west

Air temperature: -2.4 degrees celcius

Water temperature: -1.4 degrees celcius

Wind speed: 7 meters per second

Sky conditions: mostly cloudy with intervals of light snow

No sunrise or sunset – just 24 hours of daylight as sun rotates 360 degrees around the sky

One of Ute and my roles on the boat is to help Hongjie and Burcu collect data every 30 minutes 24 hours each day on various parameters of the sea ice. So today was Ice 101 – an introduction to the basics I needed to know in order to accurately observe and record for their project. First I needed to know how to identify sea ice – the slabs of ice that are formed when sea water is cooled below -1.8 degrees celcius. Sea iceThere are terms for different types of ice. Shorefast ice forms along coasts and is attached to land. Pack ice is ice floating in open water. Multiyear ice is ice that has survived at least 1 summer. First year ice is ice that has not yet survived a melting season. can come in all shapes and sizes – but typical will be a flat piece with ice underneath a layer of snow that collected on top during the winter season. Big pieces of sea ice broken as they rise and fall in the swells and either move out to sea or connect to form the pack ice surrounding the continent. Here are a few pics of the sea ice pieces we cruised through today.

The Oden can break up these pieces of ice easily – especially when they are as thin as these pieces which were only 2 or 3 meters thick.

Looking to stern, you can clearly see how effective the Oden is at leaving a clear path in this type of ice.

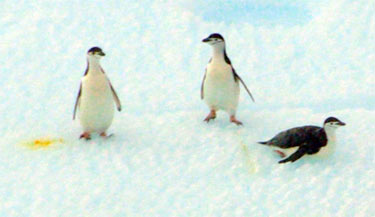

Larger pieces of sea ice are called ice floes and are typically formed over several seasons. These often provide rest and safety for both seals and penguins – as shown here by the three chinstrap penguins that we passed as they were adrift in the midst of the Amundsen Sea.

Ice that comes from a glacial source will look very different from sea ice – having a deep blue color owing to the years of being compacted under the weight of pressure of the glacier. We haven’t seen much so far – but here is a piece that we found in the Bellingshausen Sea floating amidst some huge icebergs. The Oden is capable of easily breaking up these floes up to about 10 meters thick.

The largest pieces of ice and snow that are found are the huge icebergs which form when pieces break off from the many ice shelves that flow out from the Antarctic continent. These can vary from "bergy bits” smaller than the Oden, to huge pieces as large as a small US state. As large as they often appear above water – this is only 10-20 percent of their total volume in ice. We often spot these on the horizon more than 20 miles away or even further on the ship’s radar – and the Oden avoids them since it is no match for their size or bulk – they would break the breaker!

Hopefully this give you a sense not only of the science we are doing – documenting the extent and type of sea ice – but also the beauty found down here in this mix of water and ice. Still a lot to learn – but this was the extent of Ice 101 today.

Comments