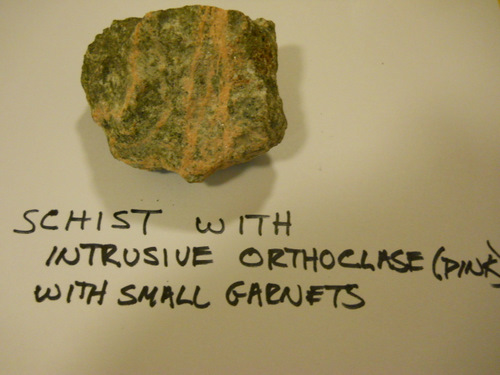

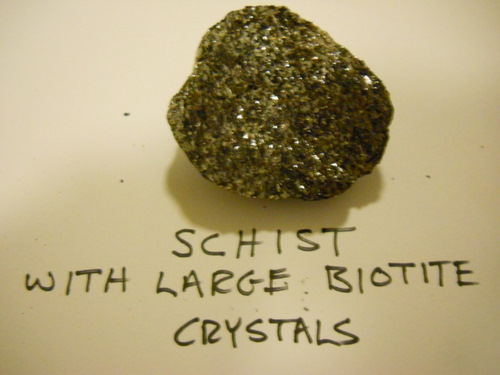

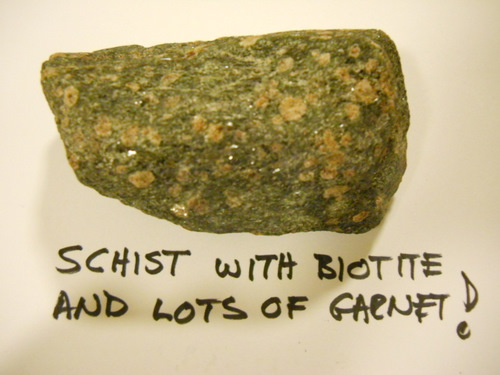

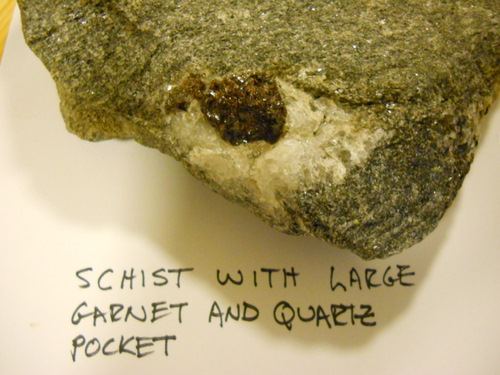

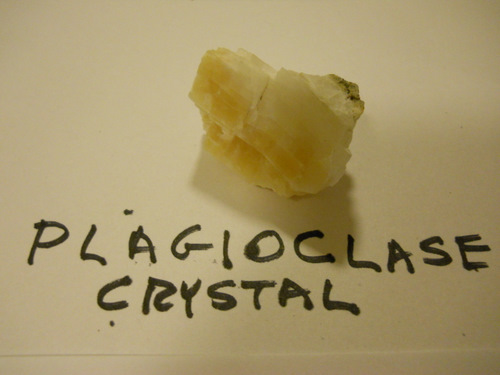

I took some time today to get a lesson from Ben about the rocks that are in the tunnel. We have been finding some rocks that are encrusted with garnets, and some that have interesting cleavage planes. Some are pink, many have large crystals, and some flake off easily. For a novice like me it is very confusing to look at what I usually pass over for "just another rock" and take a closer look to learn about the formation of these rocks millions of years ago.

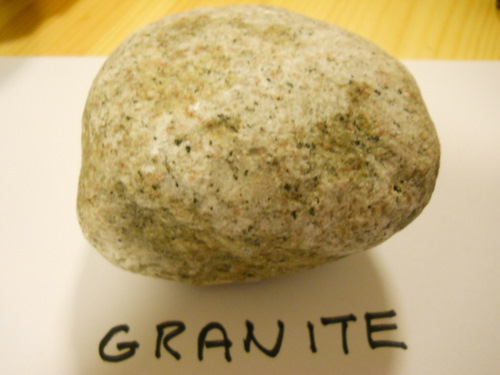

Probably the first thing that struck me when looking at these rocks and minerals is that you should not imagine them as they are right now. When they formed in volcanic magma flows they were much hotter than they are now and, depending on their depth, they were under tremendous pressure. If you have ever seen a glassblower take molten glass from a kiln then you are seeing materials at upwards of four times the hottest setting on your oven, or nearly 2000 degrees Fahrenheit. At these temperatures things appear to glow an orange like color until they cool off and reflect light instead of emitting it. Depending on the "stuff" that glassmakers put into the original mix you might get a variety of different colors in the final glass structure. Imagine that the earth is like a kiln, with many different elements mixed into it... as rivers of magma ooze from the crust of the earth they cool at different rates....slow cooling gives lots of time for large crystals to form, just like growing rock candy slowly on a string hanging in supersaturated sugar solution. Fast cooling on the other hand gives very small crystal forms. in Oregon we have basaltic rock that has very small crystals that you cannot see, this is because the basalt was formed beneath the ocean which cooled it quickly as it emerged. What I learned is that the "stuff" that makes these rocks is minerals. A mineral is just a collection of atoms forming a solid crystal, you are familiar with minerals such as Diamond, Calcite, Mica, Pyrite and others, and believe it or not ice is a mineral! There are many different kinds of minerals because there are many different kinds of atoms. Each mineral has peculiar properties, such as color, or hardness, or more importantly... melting point. Some minerals can melt at different temperatures in a kiln than others. Quartz can melt at a very low temperature whereas basalts might melt at twice that temperature. Since materials melt at different temps it means that one can be solid when the other is a liquid, so one can intrude into the other and make pretty band like structures. It is all rather complicated, but the point is that rocks tell a story about when, where and how they were formed. An experienced geologist can tell you quite a lot from a simple rock. In the photos below I show a few samples of the rocks that we found here, beneath the Svartisen glacier.

Comments