After an outstandingly busy summer once I returned home, I finally have time to sit and read through my journal entries. My initial response is: "wow, I did all that!" Thoughts from Finland tumble back into the forefront of my mind, and I now will attempt to get at least some of them down here. In reflecting back on the expedition, I see that so many thoughts and ideas were developed that I already think of this adventure as a beginning rather than having ended. However, I do need to bring closure to this set of journal entries. Thank you so much to PolarTREC for providing the tools, training and technical support to make this forum possible! So many people have already told me how much they enjoyed the photos and information, and I know I will be using the journals as a teaching tool in the future. I'll begin with some loose ends; things that I always meant to write about, but never seemed to be able to fit in, but which bring me back to some closing thoughts…

Norway

I started this journal entry two months ago, when I was visiting my friend in Tromso, Norway. Tromso, at a latitude of 69.65, is well above the Arctic Circle. However, owing to the relatively warm Gulf Stream Current, the climate is much warmer (and wetter!) than, for example, the city of Barrow, North America's northernmost city at a latitude of 71.29. Tromso has been a commercial hub for the fishing industry since its establishment, and is also now thriving on tourism.

I never finished the entry however as my friend Birgit and I took advantage of the spectacular scenery surrounding Tromso. My Finnish friends kept telling me: "the mountains are all in Norway." They were right! After a short bus ride, we arrived at a small community on Kaldfjorden. From here, we walked the rocky coastline of the fjord to Molnes, a small farm site that is now managed by the Norwegian equivalent of a department of fish and game.

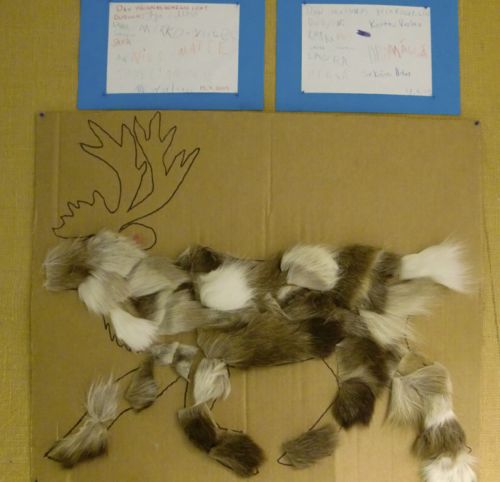

Of Sami, Reindeer, and the Collision Between Ecology and Culture

Tromso, like Kevo, is located in Lapland. As I noted in my journal entry of June 6, Lapland, homeland of the Sami, encompasses northern portions of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia's Kola Peninsula. In fact, of the estimated 80,000 Sami, about half live in Norway. These figures are from the Northern Norway Tourist Board's website.

During my stay in Finland, I had become aware of some parallels between the history of Alaska Natives and that of the Sami. On both continents, the policy of settlers was to oppressively assimilate the cultures of the indigenous peoples into their own cultures. Fortunately, this is no longer the case, and the culture and language of the Sami, as with Alaska Natives, are now seen as critically important to sustain and protect. There are many great websites to peruse for more information on the Sami. This one is published by Finland's Sami Parliament. Another that I found useful is published by the Swedish Institute.

As noted in the factsheet published by the Swedish Institute, the Sami have been connected with reindeer for at least 1,000 years.

There is a lot to be learned about the reindeer of Lapland. A great resource if you would like more information is a pamphlet that can be downloaded. This link takes you to a page where you can download the pamphlet. The download link for the English version is under the picture of the reindeer.

As a side note to learning about the Sami and reindeer, I was privileged to meet Tuisku, a registered Finnish Lapphund. Although Finnish Lapphunds are no longer the dogs of choice to herd reindeer, Elina Vainio, Tuisku's owner, is training him as a working dog.

More on Tuisku's breed can be found here.

Through conversations with people at Kevo, I came to understand that reindeer represent wealth in a Sami family. One person noted that it would be considered very bad manners to ask a Sami individual how many reindeer they own. This is akin to asking how much money they have.

However, particularly in northern Finland, reindeer wealth is having a negative impact on the natural ecosystem, illuminating a divide between science and culture. In Finland, and, as I understand, in some other parts of Lapland, there are too many reindeer for the ecosystem to support sustainably. In times past, the size of reindeer herds was dictated by the amount of winter browse, mostly lichens, available to the animals. However, now in northern Finland many herds are given supplemental feed in the winter, so many more reindeer can survive the hard months. In the summer these larger herds now range freely across the fells, eating whatever is available.

This over-browsing by reindeer is having a significant impact on the ecosystem. Dr. Otso Suominen, station manager at Kevo, noted that reindeer over-browsing in some places is so severe that it can be seen on satellite imagery. Apparently from space you can see the difference between the thick, naturally occurring lichen on the Russian side of a border fence, and the little or no lichen resulting from reindeer over-browsing on the Finnish side! I asked Dr. Suominen what was being done to address this issue. He shrugged, saying: "it's political."

I get that. No one wants to limit another person's wealth. But surely the negative impacts to the ecosystem will only worsen. So what to do?

Where Education Fits In

I feel this reindeer over-browsing issue needs to be talked about and studied by students, hopefully of all ages. Some of these students may become ecologists; some may become members of the Sami Parliament. If issues of environmental and cultural concern are talked about openly as students learn and grow, perhaps collaboration will lead to future solutions.

As a teacher, I realize that it is my responsibility to bring real life issues such as this one into the classroom. I need to find and pull together resources that enable students to study all sides of a resource issue. Let them examine and discuss it from many angles. Remembering my visit to the Arktikum in Rovaniemi, I realize that there are a wealth of issues in the circumpolar north, particularly relating to sustainable development, that can be examined and discussed by students.

Getting students from different polar places around the globe together to discuss issues and learn from one another is, I think, an even better idea. As Mark Twain said: "Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness…"

I wrote in my PolarTREC application: " I would really appreciate the opportunity to connect Alaskan students with polar science on a broader scale, showing connections between their Arctic home and either Antarctica or a different area of the circumpolar north. … I really want to show them [my students] how connected we are, how Alaskan polar science and polar issues are part of something much bigger.

As it turned out, this PolarTREC adventure in Finland has provided ME with a much stronger sense of these circumpolar connections, of cultural connections as well as scientific connections.

But After All, it IS About the Science!

I have come to realize that it is our relatively rapidly changing climate that is our most significant scientific connection – significant globally, but especially connecting the Polar Regions. I was continually struck with the similarities between northern Finland and Interior Alaska. Yes, the ecosystems have different species (as well as similar ones), but there is an overall similarity in the fact that these ecosystems are experiencing changing conditions. Kevo, a research station for 55 years, has records that document this change. I know similar records exist for Alaskan ecosystems.

Kim said that her project at Petsikko is small, and some would wonder how significant it was. However, she was doing this because there is not a lot of data on methane emissions from northern wetlands that are not underlain by permafrost. She is also contributing to the body of knowledge on year-round wetland emissions of carbon dioxide and methane. Finally, she is conducting an experiment to see if an increase in the iron content of the wetland soil will change the amounts of carbon dioxide and methane emitted by the soil microbes.

So who cares about all this? We all should! Remember, wetlands cover a significant portion of the circumpolar north, and the soil microbes in these wetlands emit significant quantities of carbon dioxide and methane. Both of these are considered greenhouse gases, contributing to the warming of our global atmosphere. In addition methane, the gas that Kim is particularly interested in gaining data on, is 25 times more effective at holding heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. So Kim's work is a small piece of a giant puzzle – a puzzle that represents an understanding of how our ecosystems work.

This brings me back to a question a student of mine asked before I left for Finland: "So since the climate is changing, how is this going to affect the ecosystem?" What a huge question! THAT is the question that all these little pieces of research are trying to answer. THAT is the question that as a teacher, I hope to motivate my students to want to find answers to… and THAT is why I teach science!!! As just one of the planet's species, we ultimately depend upon natural ecosystems for our survival – how can we not want to understand how they work, and how they are affected by change?

So a huge THANK YOU to the staff of PolarTREC for managing this program so well. THANK YOU to the National Science Foundation for funding the program. Hopefully I have been able to share a little of the impact this program has had on me, now it is time to share some of those impacts with students. THANK YOU Kim Miller for teaching me so much. THANK YOU also to the readers of these journals, you are the audience who has helped me to communicate these thoughts and images.

- < prev

- 34 of 34

Comments