This is the second journal in a series of posts about the science behind our expedition.

When I visited Ellie's lab group in Flagstaff, I discovered the Arctic Glacial Lakes project is highly collaborative, with eight Principal Investigators, six graduate students, and even more field assistants. While only four of us are working at Lake Peters this summer, many other scientists are relying on our data.

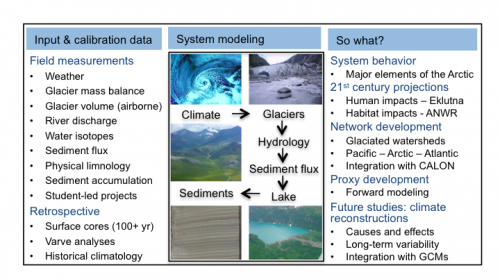

Arctic Glacial Lakes is a National Science Foundation funded project lead by Dr. Nicholas McKay, from Northern Arizona University. Many scientists with different areas of expertise lead major aspects of the project, including Darrell, our expedition leader. The project focuses on three glacial lakes across a latitudinal gradient: Lake Eklutna near Anchorage (sub-Arctic), Lake Peters, and Lake Linné in Svalbard (high Arctic). Similar data will be collected at each lake to answer broad research questions, in a long term, intensive project that seeks to understand Earth's past and present climate. As I have mentioned in previous posts, the Arctic is warming far more rapidly than the rest of the planet. Each lake is fed by glaciers, so holds a record in its sediments of glacial melt rates which can show past climate on scales from seasonal to millennial. By studying these sediment records, scientists can come to a better understanding of both human and naturally caused climate change.

Past research has used weather data to predict stream flow, but this project is taking an original approach by using stream flow and sediments to predict past weather. Many measurements will go into modeling the system – sediment cores and sediment transport, stream and lake measurements, and glacial melt and growth. Scientists hope to use these data to create a robust model of past climate and project future changes in the Arctic.

I am fortunate to join the Arctic Glacial Lakes project in its third and final year. Scientists must secure grants in order to fund their research, but research grants are highly competitive and are funded for a limited amount of time. Sadly, scientists expect dramatic cuts to funding for polar research, which will jeopardize scientists' ability to gain knowledge about complex and sensitive Arctic systems.

Comments