For months before the trip, people asked me what I was going to be doing. I could tell them I was part of the NABOS expedition (it took me a while to learn what that stood for: Nansen and Amundsen Basins Observational Systems) and that I would be part of the "Chemistry Team." For most people, that was enough. If I tried to be any more specific, eyes would start to wander, mysterious texts or phone calls would happen, etc. In reality, I really didn't know what that meant. Now, I'm starting to understand.

Stay with me for this paragraph. In coordination with the Russian scientists from the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute (AARI) from St. Petersburg, we are examining a variety of different chemicals in the ocean at different depths and multiple locations. Some of these are more well known, such as salt (salinity) or oxygen. Others are less commonly known, such as nitrates and silicates (classified as nutrients) or the trace metals barium or gallium. These all exist in different concentrations and indicate that the sampled water is from different sources - Atlantic Ocean, freshwater rivers in Siberia, etc. Regardless, measuring these chemicals allows researchers to build an ocean profile and document changes in the Arctic.

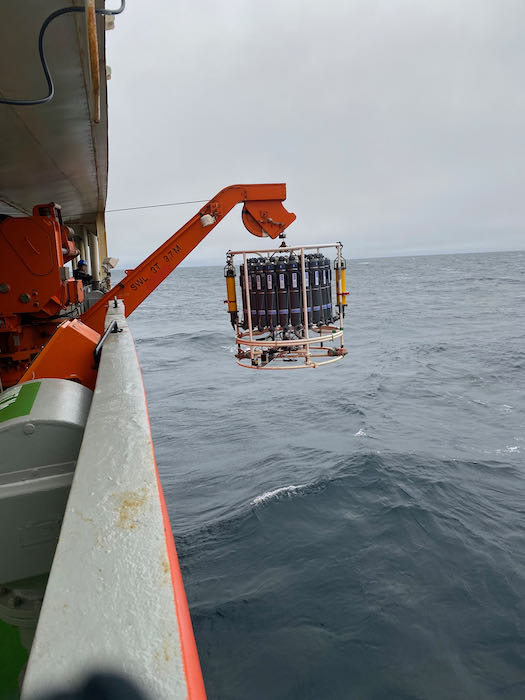

How do we collect this water? We can't just take a bucket and scoop it off the side of the ship, especially down ~3000 meters. The basic tool that we are using is the "rosette". This is a wheel of 24 Niskin bottles. Each bottle can hold 10 liters of sea water. The CTDA research tool that is submerged in the water to measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth. (Conductivity Temperature Depth) device is strapped to the bottom frame of the rosette. Other sensors, like altimeters, are attached to the CTDA research tool that is submerged in the water to measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth. and mounted to the sides of the rosette. When it is ready to be deployed, all of the bottles are held in the open position by individual plastic cables.

Then technicians hoist up the rosette and move it out through doors that open out onto the deck.

Once outside, other technicians attach it to a winch system and lower it over the deck into the water. This process is called a cast.

A crew of scientists monitors the cast from a control room. They receive live feedback about temperature and salinity, and then "trip" the bottles to close at chosen depths on the way back up from the bottom. This allows water samples to be collected throughout the water column.

Once the Rosette is back inside, the "Chemistry Team" (I think we need shirts with a logo) goes into action. AARI scientists collect for oxygen and alkalinity first because they are sensitive to mixing of air as the bottles are opened. Then, we collect for nutrients and trace metals.

We fill numbered vials (almost 3000 of them for this cruise), as well as larger bottles with the cold (it is the Arctic Ocean after all) water. Many of these samples are then frozen and will be shipped back to the University of Alaska Fairbanks for analysis, and the data will be added to the NABOS data from prior expeditions.

Comments