My fingers are numb and my toes are throbbing with icy coldness. I am once again in the deep freeze of -21˚C with a significant head wind thanks to the fans. I am fully garbed in big red and five other layers as well as two pairs of wool socks and still, the cold finds a way to seep in. Thankfully, I can step in and out as necessary, unlike being in the field, but if I step out too often the work doesn't get finished. So, I stuff my gloves with hand warmers and keep myself moving. We work for two hours in the cold with breaks about every 20 minutes just long enough to warm up the fingers.

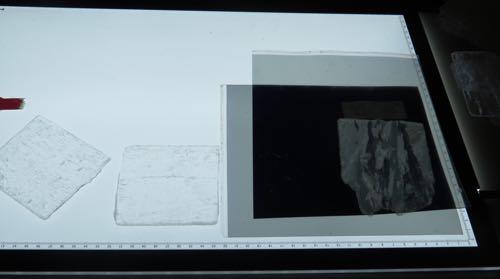

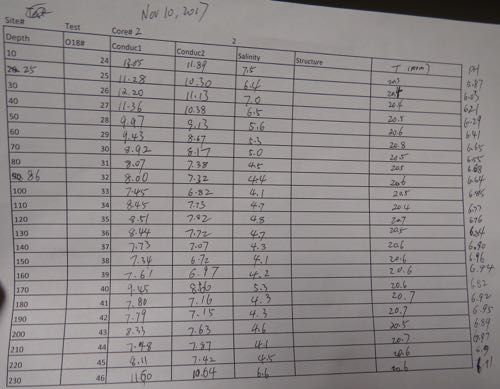

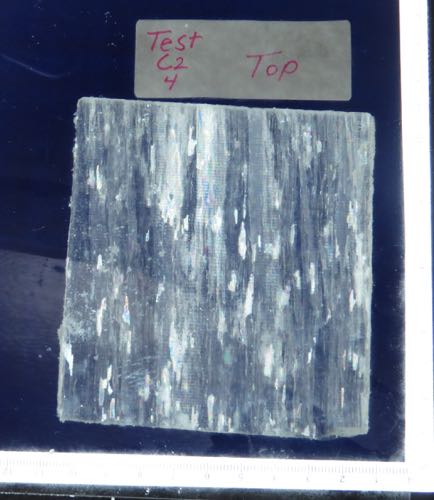

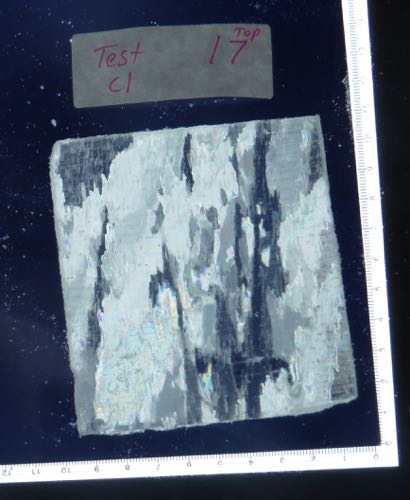

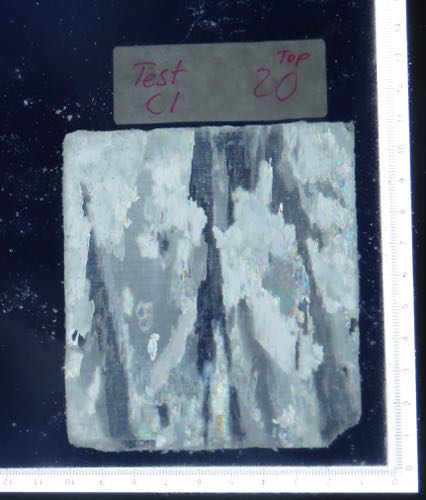

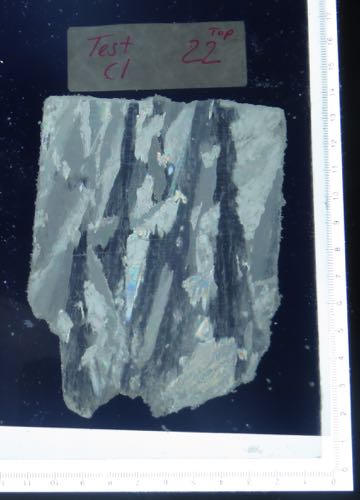

What work is happening in the cold room? I am making thin sections of our ice cores and photographing them. Hongjie takes the thin sections and brushes them to remove debris and frost to reveal a 'clean' thin section before I photograph them under two dark shades/gels set at 90˚ angles. We also cut sections for Yongli to melt so he can run salinity, pH, conductivity and a few other stable isotope measurements outside of the cold room. Sadly, Yongli cannot spend time in the freezer. Our last field day yielded a nasty frost bite to his cheek, likely from riding his snowmobile with his helmet shield up to avoid fogging on the lens. We discovered it only after getting back from the field as his face mask covered any signs of it. He is recovering and will be okay with time, but it is a definite reminder of the harsh conditions that exist here and how quickly things can turn south.

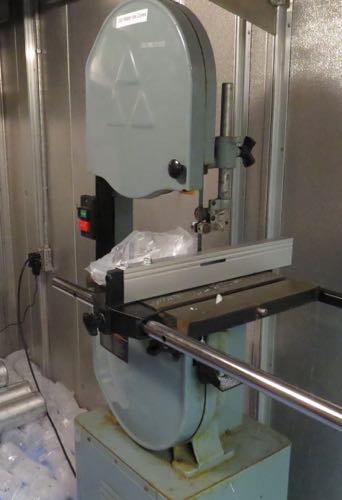

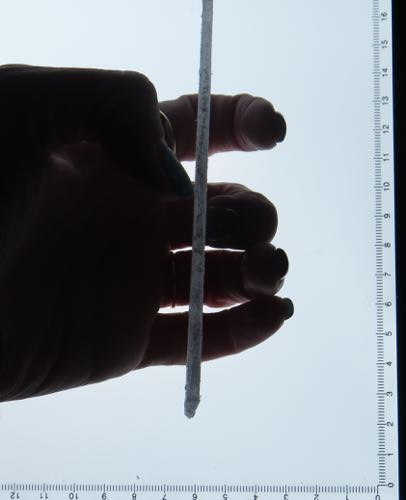

Today's images are of our lab work from the cold room. I am trying to perfect my technique on using the bandsaw. Cutting thin sections often results in broken pieces that are not usable. Ice breaks fairly easily when it becomes thin and "dry" and at -21˚C, there is no moisture to be had, everything is frozen including the brine (salty water that has a much lower freezing point). How thin can I get while keeping the section intact? That is my challenge. Thinner sections give better pictures and one can more readily determine the ice structure as to columnar, platelet or granular ice and can show where the brine channels are located as well. I am not exactly sure where all of this information will lead, but I do know we are creating a better map/picture of the Ross Sea Ice that will help us to determine how it is changing over the course of seasons and years. That in turn will hopefully help scientists understand the implications of climate change in this area.

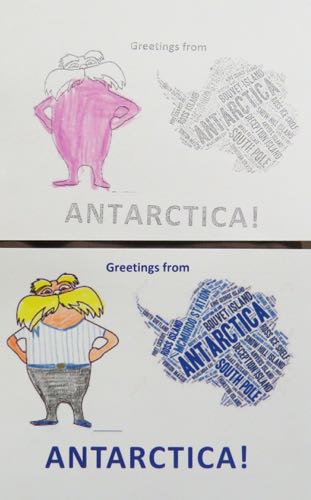

Flat Lorax was cold too and decided to warm-up by joining the McMurdo baseball team! He didn't even have to miss any field trips for tryouts! Cards today are for Jonathan in 1st grade and Bryce in APBio who was also in APES last year and will hopefully chuckle over this post!

Comments