As promised, today's post will be to explain what the IceCube NeutrinoAn elementary particle with zero charge and zero mass. An electrically neutral particle that is often emitted in the process of radioactive decay of nuclei. Neutrinos are difficult to detect, and their existence was postulated twenty years before the first one was actually discovered in the laboratory. Millions of neutrinos produced by nuclear reactions in the sun pass through your body every second without disturbing any atoms. ObservatoryA location used for observing terrestrial and/or celestial events. actually does, and why this is important. I will also summarize the events of the day.

The IceCube NeutrinoAn elementary particle with zero charge and zero mass. An electrically neutral particle that is often emitted in the process of radioactive decay of nuclei. Neutrinos are difficult to detect, and their existence was postulated twenty years before the first one was actually discovered in the laboratory. Millions of neutrinos produced by nuclear reactions in the sun pass through your body every second without disturbing any atoms. ObservatoryA location used for observing terrestrial and/or celestial events. is the world's largest and strangest telescope. Hosted by the Wisconsin IceCube Particle AstrophysicsBranch of astronomy devoted to the study of the physical characteristics and composition of objects in the sky, including how much light the stars give off and the size, mass, and temperature of planets and stars. Center (WIPAC), IceCube is an international collaboration involving over two dozen institutions. It was built over a six-season period between 2005 and 2010 just next to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. The main purpose of the observatory is to study and measure high-energy neutrinos originating from astrophysical sources, such as supernovae, gamma ray bursts, neutron stars and accretion disks around black holes. Neutrinos are lightweight, fast and highly penetrating subatomic particles that rarely interact with matter. Trillions of neutrinos travel, unnoticed, each second through a person's body. Among the sources for neutrino generation are thermonuclear processes, which also produce high-energy photons such as gamma rays and X-Rays.

This is important because extreme astrophysical events are not always observable using regular telescopes. Photons can be weakened or even stopped by intervening matter. But neutrinos, with their amazing penetrating power, make the ideal messenger particle to study these extreme events. So far in its operation, IceCube has recorded 37 meaningful neutrino events of astrophysical origin.

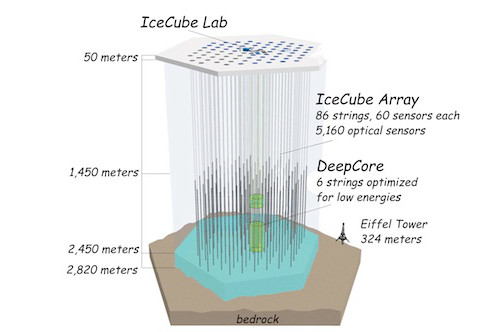

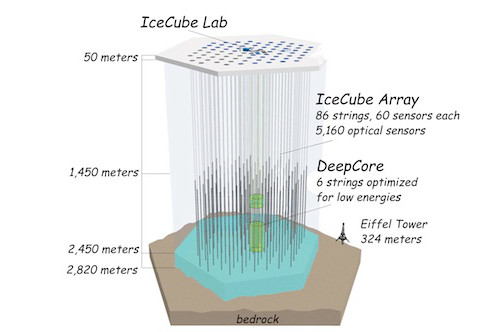

IceCube uses 5,160 sensors (otherwise known as DOMs) hanging from 86 cables, that can detect and measure blue Čerenkov light produced by neutrino interactions. Although neutrinos themselves cannot be directly measured, when they hit an atom—or more precisely, protons or neutrons in atomic nuclei—they give out secondary particles like muons, that in turn produce a trail of Čerenkov light that can be measured. The energy content and the direction of the originating neutrino can be ascertained by studying this light.

The 5,160 IceCube sensors are buried below the South Pole surface, inside a cubic kilometer of ice which is the cleanest and optically purest on Earth. This is possible because the Antarctic Plateau—where the South Pole sits at—is actually a huge glacier that rises three kilometers above the bedrock. IceCube sensors were inserted using hot water drills at depth ranging from 1.4 to 2.4 kilometers.

Early in the morning today we did the first of two scheduled IceCube webcasts with me and the IceCube team live from the South Pole. We were informed that a large number of school and colleges were joining, from Puerto Rico and every part of the United States, and also from Italy, Pakistan and India. What most people did not actually realize was that for us the webcast was done at 4:00 am! Since both the McMurdo and Amundsen-Scott stations are synchronized with New Zealand time, we at the South Pole are 17 hours ahead of Atlantic Standard Time which is in use in Puerto Rico. We all had a good time with the webcast, and a number of us were actually able to get a few additional hours of sleep after the event.

Later during the morning I went out with Sam to assist him in taking measurements on the surface tanks that make up the IceTop array. We drove the snowmobile and arrived at the same IceTop location we had been yesterday. It was cold, cloudy and windy, but we felt fine as our stay outside was brief. As explained yesterday, IceTop consists of 162 cylindrical tanks of ice, each equipped with two standard IceCube sensors capable of detecting and measuring cosmic rays. Since IceCube can also study cosmic rays—in addition to neutrinos—the deployment of IceTop will supplement cosmic ray data detected deep in the ice with data from the surface.

After lunch we went to the IceCube Laboratory (ICL) where we picked up some electronics and cables, and then set to the field again. The weather began to improve and clouds started to break. Winds subsided and we started feeling the warmth of the Sun. By 4:00 pm it was mostly clear and much warmer than it had been in the morning. We did some measurements and also plugged some cables in and out, and the warmer weather was a treat because our hands stayed warm throughout. We stayed outside for much longer than in the morning, but surprisingly were able to work very comfortably.

Según prometido hablaré hoy sobre el telescopio de neutrinos IceCube, sobré qué hace y porqué importan sus estudios. Resumiré también en este post las incidencias del día.

El telescopio de neutrinos IceCube es el mayor telescopio del mundo y también el más curioso. Auspiciado por el Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center (WIPAC), el IceCube cuenta también con la participación de más de veinte instuciones académicas. La construcción se realizó en las afueras de la estación Amundsen-Scott del polo sur, durante unos seis veranos australes entre los años 2005 y 2010. La finalidad principal del instrumento es el estudio y medición de los neutrinos de altas energías originados por fenómenos astrofísicos, tales como supernovas, estallidos de rayos gamma, estrellas de neutrones y discos de acreción en torno a agujeros negros. Los neutrinos son partículas subatómicas extremadamente livianas, rápidas y de gran penetración, por lo cual rara vez interactúan con la materia. De hecho, cada segundo una persona cualquiera se verá atravesada por billones (trillones americanos) de neutrinos. Entre los diversos mecanismos que pueden dar origen a estas partículas está la fusión termonuclear, de la cual pueden también surgir fotones altamente energéticos como los de rayos gamma y de rayos X.

Los trabajos del IceCube tienen importancia ya que los mencionados eventos extremos no siempre resultan observables mediante telescopios convencionales. En el caso de los fotones, al entrar en contacto con la materia se debilitan y hasta se detienen. Pero los neutrinos, con su asombroso poder penetrante, constituyen el medio ideal para estudiar estos eventos extremos. Hasta el momento, el telescopio IceCube ha logrado registrar unas 37 instancias de neutrinos de origen astrofisico.

El IceCube está constituido por 5,160 sensores (también llamados por el acrónimo DOMs) que cuelgan de unos 86 cables. Dichos sensores son capaces de detectar la luz azul, conocida como radiación de Čerenkov, que se origina por interacciones de los neutrinos con los átomos. Ocurre que cuando un neutrino impacta el núcleo de un átomo —y más específicamente los protones y neutrones dentro del núcleo— se originan partículas secundarias como los muones. A su paso, los muones dejan una estela azulada de luz Čerenkov que puede ser medida. Precisamente, el contenido energético y la dirección del neutrino progenitor puede determinarse mediante el estudio de dichas estelas luminosas.

Los 5,160 sensores del IceCube se encuentran insertados por debajo de la superficie del polo sur, y contenidos dentro de un kilómetro cúbico de hielo que resulta ser el más transarente y de mayor pureza óptica en nuestro planeta. Esto ha sido posible debido a que el altiplano antártico —sobre el cual ubica el polo sur— es realmente un enorme glaciar que, aunque descansa sobre tierra firme, alcanza una altura de tres kilómetros. La instalación de los sensores se realizó mediante taladros de agua caliente y alcanzando profundidades de 1.4 a 2.4 kilómetros.

Temprano en la mañana de hoy tuvimos el primero de dos webcasts, realizados en directo desde el polo sur, y programados por el equipo de IceCube. Nos comentaron que participó una gran cantidad de escuelas y universidades, ubicados desde Puerto Rico y todas partes de los Estados Unidos, hasta Italia, Pakistán e India. Sin embargo, muchos no se habían percatado que para nosotros el webcast se hizo ¡a las cuatro de la mañana! Esto ocurrió porque la estación Amundsen-Scott del polo sur —al igual que la estación McMurdo— está sincronizada con el tiempo de Nueva Zelandia, que queda 17 horas por delante que el tiempo del Atlántico utilizado en Puerto Rico. Sin duda alguna el webcast fue una experiencia muy agradable, retirándonos luego algunos de nosotros para descansar un par de horas más.

Más tarde en la mañana salí afuera con Sam para ayudarle a tomar medidas en los tanques cilíndricos empleados por el experimento IceTop. Nos trasladamos en motonieve y llegamos a la misma sección del IceTop donde habíamos trabajado ayer. Nuestra estadía fue breve, y a pesar del tiempo frío, nublado y ventoso no tuvimos contratiempos. Según había explicado ayer, el IceTop consiste de 162 cilindros de hielo, cada uno equipado con dos sensores iguales a los utilizados por IceCube, y desplegados sobre la superficie del polo sur. Dado que el telescopio Icecube puede también sondear los rayos cósmicos —además de los neutrinos— la añadidura del detector IceTop permitirá suplementar los datos sobre rayos cósmicos captados a profundidad (por IceCube) con datos obtenidos en la superficie (por IceTop).

Después de almorzar nos dirigimos al laboratorio IceCube (ICL) donde recogimos algunos cables y utilería electrónica. Salimos nuevamente afuera y tuvimos la suerte que las condiciones del tiempo empezaron a mejorar. El viento amainó, las nubes comenzaron a fragmentarse y el calor del Sol se hizo sentir. Hacia las 4:00 pm ya estaba mayormente despejado, y la temperatura se sentía también bastante menos fría que durante la mañana. Comenzamos a realizar mediciones e igualmente a conectar y desconectar cables, lo cual se hizo mucho más llevadero ya que dejamos de sentir frío en las manos. Aunque nos quedamos en el exterior por un período bastante más largo, pudimos trabajar mucho más cómodamente.

Comments