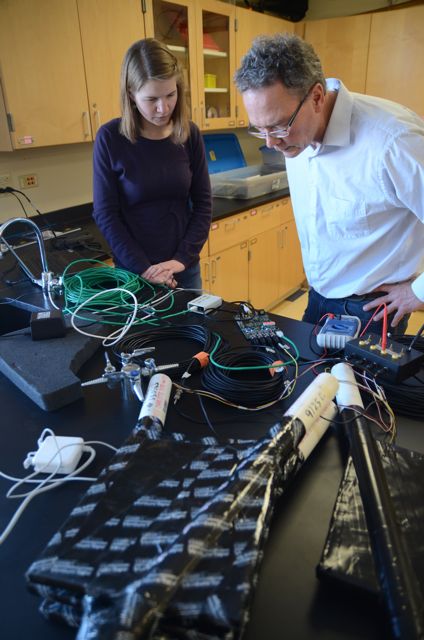

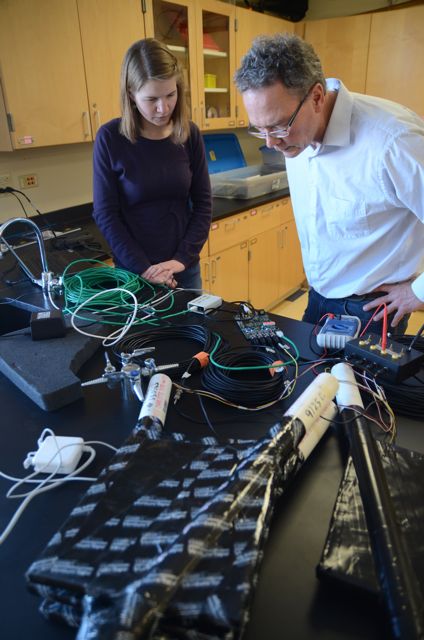

We are taking a portable cosmic ray detector to Antarctica. We will use the collect data and also to better explain the operation of the IceCube NeutrinoAn elementary particle with zero charge and zero mass. An electrically neutral particle that is often emitted in the process of radioactive decay of nuclei. Neutrinos are difficult to detect, and their existence was postulated twenty years before the first one was actually discovered in the laboratory. Millions of neutrinos produced by nuclear reactions in the sun pass through your body every second without disturbing any atoms. ObservatoryA location used for observing terrestrial and/or celestial events. in our presentation in King George Island. This educational cosmic ray detector was developed by QuarNet to help students and teachers explore some aspects of particle physics and astrophysics. Dr. Jim Madsen from the University of Wisconsin - River Falls UWRF), and scientist with IceCube, supplied the detector.

Once we set the equipment in Antarctica, we will be able to detect cosmic rays, charged particles that are more massive and easier to detect than the neutrinos. Imagine a proton moving almost at the speed of light approaching our atmosphere. The proton has been traveling for many years and is about to be destroyed. This particle has so much energy that it generates many different subatomic particles when it crashes into an atmospheric atom. The resultant particles will decay or collide themselves with other atoms. Suddenly, a shower of subatomic charged particles is created in the atmosphere, some of which make it to the surface of the Earth.

Our detector has four paddles made of a special plastic that produces light when the charged particles go through it. This process is called "scintillation", and differs from the Cherenkov radiation measured by the IceCube experiment that i continually produced by charged particles going through the ice. We detect the light produced by scintillation or Cherenkov radiation with a light sensor known as a photomultiplier tube (PMT). The PMT works like a lightbulb in reverse --- while a light bulb takes in electricity and sends out light, a photomultiplier tube takes in light and sends out an electric pulse. This light to electricity transformation is done using what is known as the photoelectric effect. The diameter of the PMT on each paddle (2 inches, 5 cm) is much smaller than those used in IceCube (10 inches, 25 cm), because scintillation produces much more light than Cherenkov radiation, and a larger fraction of this light reaches the PMT.

We can arrange the paddles in different configurations depending on what we want to study. Each paddle sends the electric pulse to a small data acquisition system, which processes and stores all the signals. We can learn about the direction from which the shower arrived if we place the paddles on the corners of an imaginary square. For example, if the shower came straight down, all four paddles would see a signal at the same time. An inclined shower gives a different time sequence.

We have set the detector to collect data in my classroom so we can practice before going to Antarctica. We hope our data from Antarctica will be useful for QuarkNet, and the AstrophysicsBranch of astronomy devoted to the study of the physical characteristics and composition of objects in the sky, including how much light the stars give off and the size, mass, and temperature of planets and stars. class at UWRF where they use the same systems,

Mediremos rayos cósmicos en la Antártida

Nos vamos a llevar un detector portátil de rayos cósmicos a la Antártida. Lo utilizaremos para tomar mediciones y para explicar mejor el funcionamiento del detector de neutrinos de IceCube Neutrino Observatory en nuestra presentación en la Isla Rey Jorge. El detector de rayos cósmicos educacional fué desarrollado por QuarNet para ayudar a estudiantes y maestros a explorar algunos aspectos de la física de partículas y de astrofísica. EL Dr. Jim Madsen de la Universidad de Wisconsin en River Falls (UWRF), y científico de IceCube nos proveyó del detector.

Una vez instalado el equipo en la Antártida comenzaremos a detectar los rayos cósmicos, partículas con carga eléctrica que tienen una masa mayor y son más fáciles de detectar que los neutrinos. Imagínate un protón desplazándose por el universo casi a la velocidad de la luz acercándose a nuestra atmósfera. El protón ha estado viajando por muchos años y está punto de ser destruido. Esta partícula tiene tanta energía que acaba por generar muchas partículas subatómicas cuando se estrella contra un átomo de la atmósfera. Las partículas resultantes pueden decaer o estrellarse a su vez en otros átomos. Se genera de repente una cascada de partículas subatómicas con carga eléctrica, de las cuales algunas logra llegar a la superficie de la tierra.

Nuestro detector tiene cuatro paletas hechas de un plástico especial que produce luz cuando partículas con carga eléctrica pasan por él. A este proceso se le conoce como "centelleo", y es diferente a la radiación Cherenkov que se produce cuando una partícula con carga eléctrica pasa por el hielo viajando más rápido que la luz en el hielo, y que mide el observatorio IceCube. Nosotros detectamos la luz que se genera por el centelleo o la radiación Cherenkov con un sensor de luz llamado tubo fotomultiplicador (PMT por sus siglas en inglés, photomultiplier tube), El PMT trabaja como un foco a la inversa --- si un foco toma electricidad y la convierte en luz, el fotomultiplicador toma luz que convierte en un pulso eléctrico. Esta transformación luz-electricidad se realiza mediante lo que se conoce como efecto fotoeléctrico. El diámetro del PMT (5 cm) en cada paleta es más pequeño que el diámetro del PMT utilizado en IceCube (25 cm), ya que el centelleo produce más luz qyue la radiación Cherenkov, y un mayor porcentaje de esta luz llega al PMT.

Podemos colocar las paletas en diferentes configuraciones dependiendo de lo que se quiera estuduar, Cada paleta manda un pulso eléctrico a un sistema pequeño de adquisición de datos, el cual procesa y almacena las señales. Podemos determinar la dirección en la que llegó la cascada de partículas si colocamos las paletas en las esquinas de un cuadrado imaginario. Si la cascada llega directamente de arriba, por ejemplo, las cuatro paletas detectarán las partículas al mismo tiempo. Una cascada que llega con cierto ángulo se registrará en cada paleta a un tiempo diferente.

Hemos instalado el detector en mi salón de clases para practicar su uso antes de ir a la Antártida. Esperamos que los datos le puedan servir a QuarkNet y al curso de astrofísica de UWRF en el que usan estos detectores.

Comments