First Flight

Today marked my first flight aboard the P3 aircraft. I walked from my room in the KISS building over to the plane this morning around 7 am - about a 5 minute commute. The only things that spoiled my otherwise pleasant stroll was the drone of the P3's APU unit in the background (the Auxiliary Power Unit - the noisy generator that powers all jet aircraft when they are on the ground) and the temperature, about -15F. I would later learn that this temperature set an all time record low for the date here in Kanger.

When I arrived at the plane the engine heaters were on in full force, pre-heating the engines so we can start them. Many Alaskan aviators are likely familiar with such an ordeal.

I measured the APU's deafening noise at 100 dB near the plane and about 85 dB inside it. Once the engines started the noise level in the back of the plane rose to 90 dB while the front - closer to the engines - registered 95 dB.

Inside, scientists, technicians, and the flight crew busied themselves with pre-flight preparations. Hard drives had to loaded and warmed, lasers and radars warmed up and turned on, calibrations made. The millions of dollars of equipment on the plane sat out overnight without heat so just like everything else the computer equipment had to be heated prior to use. And they used hair driers - euphemistically called "auxiliary thermal thermal supply units" - to accomplish this.

Overview of Operation Ice Bridge

Operation Ice Bridge (OIB) is the name of the current iteration of NASA-sponsored glacier and ice arial mapping programs. The have been doing this kind of data gathering for nearly 30 years under different names and with techniques. Some of the current members of the OIB crew date back to those early days of rudimentary technology and crude data gathering.

OIB employs a P3-Orion airplane (known to many as the "hurricane hunter") that flies over the glaciers and ice sheets of the polar regions once each year, gathering reams of data along the way. The P3 is outfitted with the following equipment:

-A half dozen sophisticated GPSA Global Positioning System (GPS) is a satellite-based navigation system used to track the location or position of objects on the Earth’s surface. systems that allow the plane to fly the same flight path one year to the next with an error of less than 50 feet.

-Two digital cameras pointing straight down that take 20 megapixel photos once each second. These photos will be layered on top of the laser data to create incredibly accurate 3D renderings of the ice surfaces.

-Four different types of radars which measure... The snow depth and layers on top of the ice. The layers of ice within the glacier (accumulation radar). The depth of the bedrock below the ice (accurate to 1 meter or so). The altitude of the surface of the glacier.

-Two laser airborne topographic mappers (ATM), one wide angle one narrow angle, that measure the shape of the ice surface across a 400 meter wide path with a resolution of 10 cm.

-An albedo spectrometer measuring the reflectivity of sunlight off the ice/snow surfaces

-An infrared radiometer which measures surface temperature

Together this suite of data taken over time provides invaluable data about the changes in the snow and ice volume throughout the polar regions. Generally speaking these scientists do not use the data collected to publish scientific papers but rather give the data to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) where anyone can access it. They literally send hard drives full of terabytes of data back to the NSIDC every few weeks.

Looking Ahead

Over the next couple of weeks I will interview the scientists, pilots, and engineers that make up the OIB team. They will describe in detail how their equipment works as well as their individual backgrounds that got them to where they are now. (Hint: They took more than one physics class!)

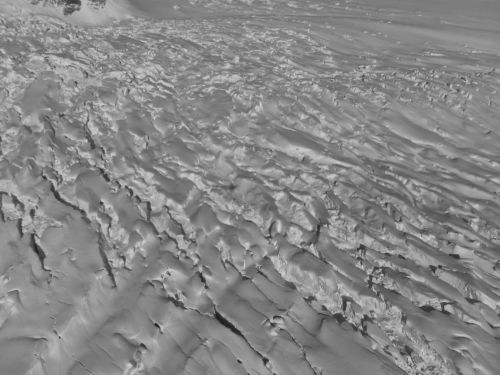

For the time being I'll leave you with a few photos from the shores of southeastern Greenland where the bulk of our flight took place today. Along the sea ice margins we could see numerous sets of polar bear tracks and seal holes. But we did not see any polar bears themselves :( We also saw one iceberg that extended a few hundred feet out of the water. It wasn't very far below our plane, which was at 500 feet at the time!

Greenland certainly has a beautiful coastline!

Comments